10x Performance Increases: Optimizing a Static Site. Getting Started with Headless Chrome Headless Chrome is shipping in Chrome 59.

It's a way to run the Chrome browser in a headless environment. Essentially, running Chrome without chrome! It brings all modern web platform features provided by Chromium and the Blink rendering engine to the command line. Why is that useful? A headless browser is a great tool for automated testing and server environments where you don't need a visible UI shell. Starting Headless (CLI) The easiest way to get started with headless mode is to open the Chrome binary from the command line. Chrome should point to your installation of Chrome. If you're on the stable channel of Chrome and cannot get the Beta, I recommend using chrome-canary: Download Chrome Canary here. Command line features In some cases, you may not need to programmatically script Headless Chrome. Printing the DOM The --dump-dom flag prints document.body.innerHTML to stdout: Create a PDF.

What is Progressive Enhancement and Why Should You Care? If you’ve been building websites and applications for even a little while, you’ve most likely already heard of progressive enhancement.

The idea has been around since 2003, it’s one that is often confused and misunderstood. For some, progressive enhancement is dead. Transparent JPG (With SVG) By Chris Coyier On Let's say you have a photographic image that really should be a JPG or WebP, for the best file size and quality.

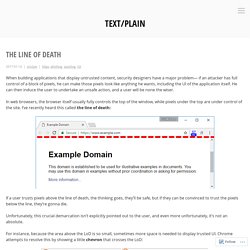

But what if I need transparency too? Don't I need PNG for that? Won't that make for either huge file sizes (PNG-24) or weird quality (PNG-8)? Let's look at another way that ends up best-of-both-worlds. The goal is to clip myself out of the image, removing the background. Now I can select the inverse of that clipping path to easily remove the background. Attempting to save this as a 1200px wide image as PNG-24 out of Photoshop ends up as about a 1MB image! The Line of Death – text/plain. When building applications that display untrusted content, security designers have a major problem— if an attacker has full control of a block of pixels, he can make those pixels look like anything he wants, including the UI of the application itself.

He can then induce the user to undertake an unsafe action, and a user will be none the wiser. In web browsers, the browser itself usually fully controls the top of the window, while pixels under the top are under control of the site. I’ve recently heard this called the line of death: If a user trusts pixels above the line of death, the thinking goes, they’ll be safe, but if they can be convinced to trust the pixels below the line, they’re gonna die.

Unfortunately, this crucial demarcation isn’t explicitly pointed out to the user, and even more unfortunately, it’s not an absolute. For instance, because the area above the LoD is so small, sometimes more space is needed to display trusted UI. …because untrusted markup cannot cross the LoD. Exotic HTTP Headers. HTTP error code 451: “Unavailable For Legal Reasons” – Naked Security. You’re probably familiar with the number 404.

It’s the return code you get when you try to access a web page that doesn’t exist. Websites are allowed to customise the message that accompanies a “page not found” error, though most of them keep the well-recognised text “404” in there somewhere. On Naked Security, for instance, you’ll see our robot mascot looking dejectedly at the digits 4-0-4 lying on the floor amidst the bits that were left over last time you tried to overhaul the washing machine by yourself. What you might not realise is that every web page (more precisely, every HTTP response) comes with a three-digit return code. The most common one is “200”, which means, very simply, “OK,” and is at the start of almost every successfully-served web request, something like this: HTTP/1.0 200 OK Content-Type: text/html <html><body><h1>Hello! Codes you might have experienced, even though the numeric values might not have been shown, include:

How Twitter deploys its widgets JavaScript. Deploys are hard and it can be frustrating to do them.

Many bugs manifest themselves during deploys, especially when there are a large number of code changes. Now what if a deploy also goes out to millions of people at once? Here’s the story of how my team makes a deploy of that scale safely and with ease. Publishers on the web use a single JavaScript file, widgets.js, to embed Twitter content on their website. Embedded Tweets, embedded timelines, and Tweet buttons are powered by the same JavaScript file, making it easy for web publishers to integrate widgets into their websites. But to ensure things stay simple for our customers, we need to take on some of the complexity. A safe deploy.