'Horrifying Step Backwards' as Sessions Retracts Guidance Designed to End Abuse of Poor by Courts. These states let police take and keep your stuff even if you haven't committed a crime. Most states in America let police take and keep your stuff without convicting you of a crime.

These states fully allow what's known as "civil forfeiture": Police officers can seize someone's property without proving the person was guilty of a crime; they just need probable cause to believe the assets are being used as part of criminal activity, typically drug trafficking. Police can then absorb the value of this property — be it cash, cars, guns, or something else — as profit, either through state programs or under a federal program known as Equitable Sharing, which lets local and state police get up to 80 percent of the value of what they seize as money for their departments. How Prison Phone Calls Became A Tax On The Poor.

On a recent sticky morning in a trailer park in Biloxi, Mississippi, Mary Jo Barnett switched on her 8-inch Samsung Galaxy tablet to speak with her 20-year-old daughter, Amber, who suffers from bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Amber is currently locked up 490 miles away in the Marion County Jail in Ocala, Florida, and these video visits are her only lifeline to her family and the outside world. Without communication, Mary Jo says she fears her daughter may suffer a mental breakdown or start a fight, which could lengthen her jail sentence. “Just getting to talk to her and interacting with her can make the difference in her mindset,” Mary Jo says. Communication, however, is enormously expensive for Mary Jo, a 52-year-old grandmother who lives on $733 monthly disability checks.

The video visitations cost $10 per 30-minute visit, or $19.99 per month. Studies have consistently shown that communication with family members lowers the rates of inmate recidivism. New report: In tough times, police start seizing a lot more stuff from people. Recent years have brought public scrutiny on a controversial law enforcement practice known as civil asset forfeiture, which lets police seize and keep cash and property from people who are never convicted — and in many cases, even charged — with wrongdoing.

But despite a growing public outcry spurred in part by news investigations and congressional hearings, a new report Tuesday from the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit civil-liberties law firm, finds that the past decade has seen a "meteoric, exponential increase" in the use of the practice. The government does not measure the number of times per year that assets are seized. But one common measure of the practice is the amount of money in the asset forfeiture funds of the Department of Justice and the U.S. Treasury, the two agencies that typically perform forfeitures at the federal level. In 2008, there were less than $1.5 billion in the combined asset forfeiture funds of the Justice Department and the U.S. Profit motive. The feds have resumed a controversial program that lets cops take stuff and keep it. Under U.S.

Attorney General Loretta Lynch, the Justice Department has resumed a practice where police officers can seize and keep cash and property from people who are never convicted of a crime. The Prison-Commercial Complex. Photo ORANGE, Conn. — LAST week, an order from the Federal Communications Commission that caps rates for United States prison telephone calls went into effect.

A late stay by a federal appeals court, sought by phone companies suing the F.C.C., had threatened to delay the order’s implementation. The stay affects several portions of the F.C.C.’s regulation, but key rate caps and restrictions on charges now apply — to the delight of advocates for prisoners and their families who have long criticized the call rates as a form of price gouging. But the celebrations are premature. Companies that cater to correctional populations target people who have a desperate need and no other options.

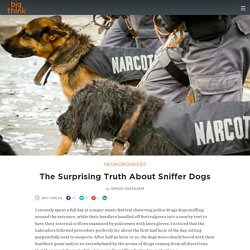

Despite the rate-capping order, the phone companies’ litigation against the F.C.C.’s efforts to rein in their excessive charges is likely to continue. The Surprising Truth About Sniffer Dogs. By Simon Oxenham.

The Woman Who Spent Six Years Fighting a Traffic Stop. N ext year, come summer, Edward Larvadain, Jr. will have been an attorney for 50 years.

He’s had a memorable run, enough so that last year he was inducted into the Southern University Law Center Hall of Fame. As a civil rights activist, he was arrested during a 1961 sit-in and served 31 days in jail. Five years later, when he began practicing, rural Louisiana had so few black lawyers that a brief filed by the U.S. Department of Justice made note of him joining the bar.

Search and Seizure: Crash Course Government and Politics #27. NewsChannel 5 Investigates: Policing for Profit (2014) - Part 1. NewsChannel 5 Investigates: Policing for Profit (2014) - Part 2. NewsChannel 5 Investigates: Policing for Profit (2014) - Part 3. NewsChannel 5 Investigates: Policing for Profit (2014) - Part 4. NewsChannel 5 Investigates: Policing for Profit (2014) - Part 5. NewsChannel 5 Investigates: Policing for Profit (2014) - Part 6.