Viewpoint: Mars - what we've learnt in five years. On 25 May, it will be five years since Nasa's robotic spacecraft Phoenix touched down in the Martian "arctic".

Here, Dr Tom Pike, one of the mission scientists on Phoenix, explains what we've learnt about the Red Planet in that time. I'm tightly sandwiched between missions to Mars. I'm still analysing data from Phoenix, while building hardware for the seismometers launching on InSight. In my spare time, I like to keep an eye on the data coming down from Curiosity. Although workdays and weekends are rather blurred, there are some dates I take great care to remember.

Five years ago today, the Phoenix Lander started its descent towards the northern plains of Mars. The elation I felt when Phoenix had touched down safely was intense and immediate, but it is only now possible to judge what the mission really achieved. To make any assessment, I first have to look back from the mission, to see what Phoenix added to our growing knowledge of the Red Planet. How We Will Terraform Mars. Actually, terraforming CAN change the martian gravity.

You forget, all worlds are constructed, in part or in whole, by the collision of other bodies to form more MASSIVE worlds. Sometimes collisions can shatter a world and remove mass, but more often the process increases planetary mass. A planet's mass determines its gravity. Therefore if we impact high-density materials such as nickle, iron, and similar heavy elements, we can slowly add to the planet's mass. Even lighter materials such as water and carbon dioxide add to a planet's overall mass - although they have far less an effect. Granted, this class of terraforming is only palatable if the planet is completely lifeless - because one way or another, once you start this process, everything on the current surface is likely toast. Even with enough time, energy and material you can create a molten iron core again. Just because such feats are seemingly out of reach now doesn't mean they will remain that way. Permafrost microbes survive conditions similar to those on Mars.

If we assume that life got started during the warmer, wetter conditions of Mars' past, could it still be hanging on somewhere under its frigid, sparse atmosphere?

Without a careful examination of hundreds of potential habitats around the red planet, that question is probably impossible to definitively answer. But we can get a sense of whether that's possible by examining life in extreme conditions on Earth. In the latest effort of this sort, an international team of researchers have taken samples from deep in the Siberian permafrost and put them under conditions similar to those on Mars: freezing, low pressure, and devoid of oxygen. Despite the unpleasant environment, several clones of bacteria grew out.

Mars May Be Habitable Today, Scientists Say. LOS ANGELES — While Mars was likely a more hospitable place in its wetter, warmer past, the Red Planet may still be capable of supporting microbial life today, some scientists say.

Ongoing research in Mars-like places such as Antarctica and Chile's Atacama Desert shows that microbes can eke out a living in extremely cold and dry environments, several researchers stressed at "The Present-Day Habitability of Mars" conference held here at the University of California Los Angeles this month. And not all parts of the Red Planet's surface may be arid currently — at least not all the time. Evidence is building that liquid water might flow seasonally at some Martian sites, potentially providing a haven for life as we know it. NASA Curiosity rover digs Mars, finds sulfur, chlorine and organic traces of unknown origin. Mars Has "Oceans" of Water Inside? Richard A.

Lovett Mars could have entire oceans' worth of water locked in rocks deep underground, scientists say. The finding suggests that ancient volcanic eruptions may have been major sources of water on early Mars—and could have created habitable environments. According to a new study, Martian meteorites contain a surprising amount of hydrated minerals, which have water incorporated in their crystalline structures. In fact, the study authors estimate that the Martian mantle currently contains between 70 and 300 parts per million of water—enough to cover the planet in liquid 660 to 3,300 feet (200 to 1,000 meters) deep.

"Basically the amount of water we're talking about is equal to or more than the amount in the upper mantle of the Earth," which contains 50 to 300 parts per million of water, said study leader Francis McCubbin, a planetary scientist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. Water seems to flow freely on Mars. Dark streaks that hint at seasonally flowing water have been spotted near the equator of Mars1.

The potentially habitable oases are enticing targets for research. But spacecraft will probably have to steer clear of them unless the craft are carefully sterilized — a costly safeguard against interplanetary contamination that may rule out the sites for exploration. River-like valleys attest to the flow of water on ancient Mars, but today the planet is dry and has an atmosphere that is too thin to support liquid water on the surface for long.

However, intriguing clues suggest that water may still run across the surface from time to time. Massive flood scarred the surface of Mars less than 500 million years ago. Mars clearly had a watery history, with strong evidence of flowing streams and even some indications that an ocean was present in the distant past.

The fate of Mars' water isn't understood, but there's evidence that some of it may have gone underground and is currently circulating in the bedrock of the red planet. A study being released by Science finds further evidence that some of Mars' underground waters have burst to the surface violently. Using radar imaging, a team of scientists has tracked a series of channels buried under more recent features and has followed them back toward the source. The imaging showed that the main channel was about 40 kilometers wide and at least 70 meters deep. That's roughly the same size as the features carved by the largest well-characterized floods on Earth. Curiosity Rover Makes Big Water Discovery in Mars Dirt, a 'Wow Moment'

Future Mars explorers may be able to get all the water they need out of the red dirt beneath their boots, a new study suggests.

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has found that surface soil on the Red Planet contains about 2 percent water by weight. That means astronaut pioneers could extract roughly 2 pints (1 liter) of water out of every cubic foot (0.03 cubic meters) of Martian dirt they dig up, said study lead author Laurie Leshin, of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y. "For me, that was a big 'wow' moment," Leshin told SPACE.com. New Mars Meteorite Contains 10 Times More Water Than Previous Finds.

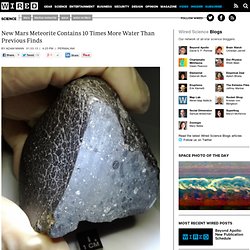

Scientists have identified a never-before-seen type of meteorite from Mars that has 10 times more water and far more oxygen in it than any previous Martian sample.

The meteorite was found in the Sahara Desert in 2011 and has the official name of Northwest Africa 7034. It is a small basaltic rock — nicknamed “Black Beauty” – which means it formed from rapidly cooling lava. The meteorite is about 2.1 billion years old, from a period known as the Martian Amazonian epoch, and provides scientists with their first hands-on glimpse of this era. Around 110 Martian meteorites have been found on Earth. Most were probably blown off the Red Planet during a large asteroid impact and subsequently crashed on our own world. Almost all other Mars rocks on Earth fall into a category known as the SNC group (Shergottites, nakhlites, and chassignites). Scientists analyzed the rock through several methods. Image: NASA. Wanted: People willing to die on Mars - World.