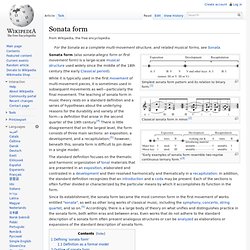

Lenny Tab by Stevie Ray Vaughan. Sonata form. Simplest sonata form pattern and its relation to binary form.[1] Classical sonata form in minor.[2] "Early examples of sonata form resemble two-reprise continuous ternary form.

"[3] Sonata form (also sonata-allegro form or first movement form) is a large-scale musical structure used widely since the middle of the 18th century (the early Classical period). Since its establishment, the sonata form became the most common form in the first movement of works entitled "sonata", as well as other long works of classical music, including the symphony, concerto, string quartet, and so on.[5] Accordingly, there is a large body of theory on what unifies and distinguishes practice in the sonata form, both within eras and between eras.

Defining 'sonata form'[edit] This model was derived from study and criticism of Beethoven's piano sonatas. Definition as a formal model[edit] A sonata-allegro movement is divided into sections. These variations include, but are not limited to: Tempo. Play In musical terminology, tempo ("time" in Italian; plural: tempi or tempos) is the speed or pace of a given piece.

Measuring tempo[edit] Electronic metronome, Wittner model The tempo of a piece will typically be written at the start of a piece of music, and in modern Western music is usually indicated in beats per minute (BPM). This means that a particular note value (for example, a quarter note or crotchet) is specified as the beat, and that the amount of time between successive beats is a specified fraction of a minute.

With the advent of modern electronics, BPM became an extremely precise measure. As an alternative to metronome markings, some 20th-century composers (such as Béla Bartók and John Cage) would give the total execution time of a piece, from which the proper tempo can be roughly derived. Tempo is as crucial in contemporary music as it is in classical. Fugue. The English term fugue originated in the 16th century and is derived from the French word fugue or the Italian fuga.

This in turn comes from Latin, also fuga, which is itself related to both fugere ("to flee") and fugare ("to chase").[1] The adjectival form is fugal.[2] Variants include fughetta (literally, "a small fugue") and fugato (a passage in fugal style within another work that is not a fugue).[3] Musical outline[edit] A fugue begins with the exposition and is written according to certain predefined rules; in later portions the composer has more freedom, though a logical key structure is usually followed. Further entries of the subject will occur throughout the fugue, repeating the accompanying material at the same time.[13] The various entries may or may not be separated by episodes. What follows is a chart displaying a fairly typical fugal outline, and an explanation of the processes involved in creating this structure.

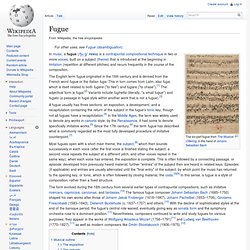

Caesura. An example of a caesura in modern western music notation.

Brief caesura used in choral works. In musical notation, the symbol for a caesura is a pair of parallel lines set at an angle, rather like a pair of forward slashes: //. The symbol is popularly called "tram-lines" in the U.K. and "railroad tracks" in the U.S. Examples[edit] In the following examples, the symbol for the caesura in scanning poetry, the "double pipes" ("||"), are inserted into the text of the poem to indicate the position of the audible pause.

Homer[edit] Caesurae were widely used in Greek poetry, for example, in the opening line of the Iliad: μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ || Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος ("Sing, o goddess, the rage || of Achilles, the son of Peleus. ") This line includes a masculine caesura after θεὰ, a natural break that separates the line into two logical parts. Latin[edit] Caesurae were widely used in Latin poetry, for example, in the opening line of Virgil's Aeneid: Arma virumque cano || Troiae qui primus ab oris Old English[edit]

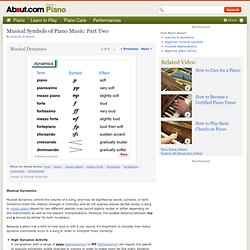

Musical Dynamics - Musical Volume and Dynamics. Musical Dynamics Musical dynamics control the volume of a song, and may be signified by words, symbols, or both.

Dynamics mark the relative changes in intensity, and do not express precise decibel levels; a song in mezzo-piano played by two different pianists may sound slightly louder or softer depending on the instruments as well as the players’ interpretations. However, the audible distance between mp and p should be similar for both musicians. Because a piano has a limit to how loud or soft it can sound, it’s important to consider how many dynamic commands occur in a song in order to interpret them correctly: Continue With Musical Dynamics: ► Learn More Dynamics Symbols & Terminology ► Quiz Yourself on the Dynamics Symbols!

Artists. Instruments.