Tetrapharmakos. The Tetrapharmakos (τετραφάρμακος) "four-part remedy" is a summary of the first four of the Κύριαι Δόξαι (Kuriai Doxai, the forty Epicurean Principal Doctrines given by Diogenes Laërtius in his Life of Epicurus) in Epicureanism, a recipe for leading the happiest possible life.

They are recommendations to avoid anxiety or existential dread.[1] The four-part cure[edit] As expressed by Philodemos, and preserved in a Herculaneum Papyrus (1005, 4.9–14), the tetrapharmakos reads:[4] This is a summary of the first four of the forty Epicurean Principal Doctrines (Sovran Maxims) given by Diogenes Laërtius, which in the translation by Robert Drew Hicks (1925) read as follows: 1. 2. 3. 4. Don't fear god[edit] In Hellenistic religion, the gods were conceived as hypothetical beings in a perpetual state of bliss, indestructible entities that are completely invulnerable. Don't worry about death[edit] As D. What is good is easy to get[edit] What is terrible is easy to endure[edit] References and notes[edit] Chariot Allegory. Myth of Er. A Renaissance manuscript Latin translation of The Republic The story begins as a man named Er (/ɜr/; Greek: Ἤρ, gen.: Ἠρός (not to be confused with Eros); son of Ἀρμένιος, Armenios of Pamphylia) dies in battle.

When the bodies of those who died in the battle are collected, ten days after his death, Er remains undecomposed. Two days later he revives on his funeral-pyre and tells others of his journey in the afterlife, including an account of reincarnation and the celestial spheres of the astral plane. The tale introduces the idea that moral people are rewarded and immoral people punished after death. Although called the Myth of Er, the word "myth" means "word, speech, account", rather than the modern meaning. Er's tale[edit] With many other souls as his companions, Er had come across an awesome place with four openings - two into and out of the sky and two into and out of the earth. Then, by their lottery tokens, they were required to come forward in order and choose their next life.

Ship of state. [edit] Plato establishes the comparison by describing the steering of a ship as just like any other "craft" or profession - in particular, that of a statesman.

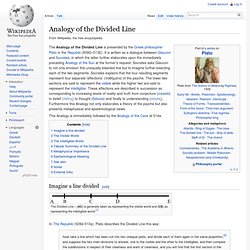

He then runs the metaphor in reference to a particular type of government: democracy. Plato’s democracy is not the modern notion of a mix of democracy and republicanism, but rather direct democracy by way of pure majority rule. In the metaphor, found at 488a-489d, Plato's Socrates compares the population at large to a strong but nearsighted shipowner whose knowledge of seafaring is lacking. Analogy of the divided line. This Analogy is immediately followed by the Analogy of the Cave at 514a.

Imagine a line divided[edit] The Divided Line – (AC) is generally taken as representing the visible world and (CE) as representing the intelligible world.[1] In The Republic (509d-510a), Plato describes the Divided Line this way: Ring of Gyges. The legend[edit] Gyges of Lydia was a historical king, the founder of the Mermnad dynasty of Lydian kings.

Various ancient works—the most well-known being The Histories of Herodotus[2]—gave different accounts of the circumstances of his rise to power.[3] All, however, agree in asserting that he was originally a subordinate of King Candaules of Lydia, that he killed Candaules and seized the throne, and that he had either seduced Candaules' Queen before killing him, married her afterwards, or both. In Glaucon's recounting of the myth (which is clearly not based on historical fact), an unnamed ancestor of Gyges[4] was a shepherd in the service of the ruler of Lydia. After an earthquake, a cave was revealed in a mountainside where he was feeding his flock. Entering the cave, he discovered that it was in fact a tomb with a bronze horse containing a corpse, larger than that of a man, who wore a golden ring, which he pocketed. Metaphor of the sun. Socrates says that the sense of sight is unusual.

He argues that for the other senses to be used all that is needed is the sense itself and that which can be sensed by it. (e.g., to taste sweetness, one needs the sense of taste and that which can be tasted as sweet) The sense of sight, however, needs something additional, namely light, in order to see that which is visible. Both the sense of sight is able to see and that which is visible can be seen when light is present but of course not when absent.

Socrates exclaims “Then with no slight idea have the sense and the power of being seen been united by a more precious bond than the other pairs! —unless light is quite without worth.” (507e-508a) Having made these claims, Socrates asks Glaucon, “…which of the gods in heaven can you put down as cause and master of this, whose light makes our sight see so beautifully and the things to be seen?” Jump up ^ The Republic VI (509b); trans.