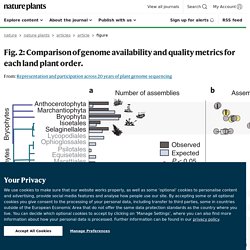

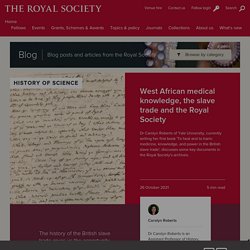

Fig. 2: Comparison of genome availability and quality metrics for each land plant order. A, The number of species with publicly available genome assemblies as of January 2021 (n = 798) versus the number expected for each order.

Significance values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test. Orders with no genome assemblies are shown in grey. Bryophytes are plotted at the phylum level, but Extended Data Fig. 2 shows bryophyte orders. Orders showing significant over- or under-representation are marked with asterisks. Over-represented orders include Brassicales (P = 3.03 × 10–13), Cucurbitales (P = 0.0038), Fagales (P = 0.0003), Malvales (P = 0.0084), Rosales (P = 0.0286) and Solanales (P = 1.27 × 10–6). Racist Relics: An Ugly Blight On Our Botanical Nomenclature.

The names Nigger's-hand cactus and Niggerfinger cactus have been given by Margaret Martin and her coauthors in the popular Cacti and Their Cultivation (New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971) for Opuntia clavarioides, a small cactus with bizarre, slender, cylindrical branches.

Alfred Graf, author of the widely used botanical guidebook Exotica (East Rutherford, N.J., Roehrs Co. Inc., 1980), gives Nigger-wool as a common name for the New Zealand Wire Vine (Muehlenbeckia complexa), apparently in reference to the basket plant's twining, wire-like purplish brown stems. Occasionally one can still hear Brazil nuts (Bertholletia excelsa) referred to as Nigger-toes. Meanwhile, horticulturist P.A. Munz's California Flora and California Desert Wildflowers (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1970) lists Niggerhead cactus as the accepted common name for Echinocactus polycephalus, a small barrel cactus native to California's southern deserts.

Science Museum Group Journal - Book review: Green Unpleasant Land: Creative Responses to Rural England’s Colonial Connections by Professor Corinne Fowler. On a freezing Bradford afternoon in January 1989, a thousand protestors came together with a common purpose.

While the press looked on, they brought out a copy of a book mounted on a wooden pole, held it aloft and set it on fire. The book was The Satanic Verses, a magical realist novel by the British-American author Salman Rushdie, parts of which the Muslim protestors believed to be blasphemous. They wanted to bring attention to that fact and in this they were successful, possibly more than they could have imagined. Similar protests followed all around the world, some of which were violent. Addressing unconscious coloniality and decolonizing practice in geoscience.

Pablo Gomez - Slave Trading and Medical Arithmetics in the Early Seventeenth-Century Iberian Atlantic. Event Description This lecture examines the role of accounting and financial practices in the ideation of models for the quantification of human bodies, disease, population health, and risk in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth-century world of the transatlantic slave trade.

Pablo Gomez considers the conceptual logic appearing in the registration and bureaucratization of the value of slave bodies, and their insertion in the logic of the early modern state and its mercantile economies. He argues that the constitutive elements of what would later become known as medical arithmetics, and ideas about possibilities for the quantification of risk as related to human bodies and disease, appears for the first time in widely used models for the registration and bureaucratization of the value of slave bodies, and their insertion in the organizational language of early modern Iberian states and their mercantile economies. Event Speaker. West African medical knowledge, the slave trade and the Royal Society. In January 2013, while a doctoral student at Harvard University, I travelled to the UK to conduct dissertation research.

As a historian of medicine and science studying slavery and the Atlantic slave trade, visiting the Royal Society was essential. Before my visit, I pored over Thomas Sprat’s first official history of the Royal Society, published in 1667. According to Sprat (p.407), the Royal Society and the Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa (one of Britain’s early slave trading corporations) were ‘twin sisters’:

Fascinating and thought-provoking #AnnualDigiLecture @UKNatArchives by @laurenfklein. I loved Mimi Ọnụọha's The Library of Missing Datasets as I grapple with the huge gaps and silences in my project sources. It’s time to decolonise botanical collections. JoNSC Vol6 DasandLowe2018. Decolonizing Herbaria begins with acknowledging the colonial legacy. See this talk at #Botany2021 Elucidating the imprint of colonialism in the herbarium: past, present, and future by Daniel Park (Park Lab at Purdue)

The Life and Work of Robert Alexander Gilbert: Empowering New Insights through Digitization and Transcription of Archival Materials. This post is part of a series from the Ernst Mayr Library exploring the digitization and transcription of ornithologist William Brewster’s archival materials and the insights and scholarship made possible thanks to this work.

Robert A. Gilbert, far right, at William Brewster’s cabin at Pine Point, Umbagog Lake, Maine. From the collection of the Museum of American Bird Art, Massachusetts Audubon Society and reproduced with their permission. Natural Sciences Collections Association. Most stories told by natural history museums inevitably concern natural history, using collections to engage people with biological and geological mechanisms behind life on earth.

Such institutions typically aim to inspire visitors and other audiences to care for the natural world. However, including narratives exploring troubling social histories attached to the acquisition of natural history specimens is an important step towards decolonising natural history museums. Telling these stories is vital in enabling museums to better reflect the societies they serve. In this paper we use the specific histories of two specimens as case studies that involve issues which museums interested in decolonising their collections could explore and share with their audiences. Colonial Critters: Decolonising the Powell-Cotton Museum. Racism in Taxonomy: What's in a Name? - Hoyt Arboretum. Inequities run deep in the natural sciences, and it’s apparent in the racist and xenophobic nomenclature of some trees and plants.

Even within the last 30 years, anti-Black slurs were commonly used to describe plants. There are many examples, including Echinocactus polycephalus and Bertholletia excelsa (Brazil nuts), that carry ugly colloquial names that only recently fell out of common usage. Ep7: Decolonising natural history with Miranda Lowe. How Conservation Is Shaped by Settler Colonialism. When we talk about conservation land, we usually mean areas kept in a pristine, natural state, from which people are barred from living.

But environmental philosopher Yogi Hale Hendlin argues that this reinforces a perspective about land ownership that undermines conservation goals. Hendlin writes that between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, Europeans built their empires on the legal concept of terra nullius, meaning “no one’s land.” Colonial powers justified taking land to cultivate by defining it as wild, or vacant, even when—as in most places, including most of the Americas—people were already living on the land and modifying it to meet their needs. Herbarium specimen labels can include offensive, culturally/racially insensitive locality names. Often outdated place names. How do folks deal with these? I recall reading a blog on this topic, but can't recall. Any thoughts on transcribing these labels,

The East India Company at Home, 1757 1857 – UCL Press. The East India Company at Home, 1757–1857 explores how empire in Asia shaped British country houses, their interiors and the lives of their residents.

It includes chapters from researchers based in a wide range of settings such as archives and libraries, museums, heritage organisations, the community of family historians and universities. It moves beyond conventional academic narratives and makes an important contribution to ongoing debates around how empire impacted Britain. The volume focuses on the propertied families of the East India Company at the height of Company rule.

From the Battle of Plassey in 1757 to the outbreak of the Indian Uprising in 1857, objects, people and wealth flowed to Britain from Asia. As men in Company service increasingly shifted their activities from trade to military expansion and political administration, a new population of civil servants, army officers, surveyors and surgeons journeyed to India to make their fortunes. Telling the Truth About Who Really Collected the “Hero Collections”. – NatSCA. Written by Jack Ashby, Assistant Director of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge. One way that museums can decolonise their collections is to celebrate the true diversity of all the people that were ultimately responsible for making them.

We often say things like, “This specimen was collected by Darwin”, or whichever famous name put a collection together, when in reality we know that often they weren’t actually the ones who found and caught the animal. Museums can be rightly proud of their “hero collections” and the famous discoveries represented by them. A Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Reading List, with Special Emphasis on Natural Sciences and Natural History Museums. As the hub for digitization of U.S. natural history collections, iDigBio aims to engage our community in promoting a more diverse, equitable, inclusive, and actively anti-racist community. To that end, the iDigBio team focused on issues of Education, Outreach, Diversity, and Inclusion has compiled this reading list to begin conversations in the classroom, in museum collections, and among colleagues.

The iDigBio EODI Team: Alnycea Blackwell, Adania Flemming, Molly Phillips, and David Blackburn. We welcome suggestions for additions. Please contact Molly Phillips, EODI Coordinator for iDigBio. <mphillips@flmnh.ufl.edu> Those Famous White Naturalists Who Made History Would Have Failed If Not For Their Enslaved Or Indigenous Assistants And Collaborators. Colonial Critters: Decolonising The Powell-Cotton Museum. Presented by Rachel Jennings, Powell-Cotton Museum.

Abstract The Powell-Cotton Museum’s dioramas are visual spectacles that delight audiences, but they aren’t representations of ‘real life’. Starting in September 2020, we are undertaking a project called ‘Colonial Critters’, which will look critically at the context in which these displays were created. “Decolonising the Curatorial Process” – a new film, produced and directed by Dr Orson Nava – Decolonial Dialogues. Documentary film: “Decolonising the Curatorial Process” (Duration: c. 40 minutes). Orson Nava’s documentary film “Decolonising the Curatorial Process” features conference footage and recordings of individual interviews with a range of contributors who examine ways that decolonial activists, museologists, political scientists, historians and other scholar-activists from South Africa, Kenya and the UK are working with radical museum curators to challenge Eurocentric approaches to the study of history. These important museum-based consultations, research narratives and conference discussions also foreground the lived experiences (and collective memories) of communities from the global South who have been severely impacted by the racialised violence, cultural conflicts and legacies of the colonial past.

Case Studies Two of the key case study institutions featured in the film include: #DLFMuseums: Decolonizing Botanical Catalogs. In September I spoke with Nuala Caomhánach, Rashad Bell, DePrator, Wambui Ippolito + Laura Briscoe to talk about Black botany + decolonizing living collections. We've extended that into 2 posts for @JHIdeas.