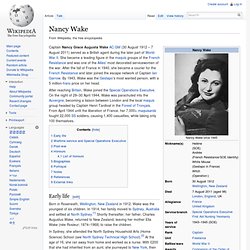

Cactusrabbit: flatmongoose: dragonblade: Nancy Wake. Early life[edit] Born in Roseneath, Wellington, New Zealand in 1912, Wake was the youngest of six children.

In 1914, her family moved to Sydney, Australia and settled at North Sydney.[1] Shortly thereafter, her father, Charles Augustus Wake, returned to New Zealand, leaving her mother Ella Wake (née Rosieur; 1874–1968) to raise the children. In Sydney, she attended the North Sydney Household Arts (Home Science) School (see North Sydney Technical High School).[2] At the age of 16, she ran away from home and worked as a nurse. With £200 that she had inherited from an aunt, she journeyed to New York, then London where she trained herself as a journalist. In the 1930s, she worked in Paris and later for Hearst newspapers as a European correspondent. Wartime service and Special Operations Executive[edit] In 1937, Wake met wealthy French industrialist Henri Edmond Fiocca (1898–1943), whom she married on 30 November 1939.

Wake had been arrested in Toulouse,[when?] Post-war[edit] Honours[edit] “‘We Have Always Fought’: Challenging the ‘Women, Cattle and Slaves’ Narrative” by Kameron Hurley — A Dribble of Ink. I’m going to tell you a story about llamas.

It will be like every other story you’ve ever heard about llamas: how they are covered in fine scales; how they eat their young if not raised properly; and how, at the end of their lives, they hurl themselves – lemming-like- over cliffs to drown in the surging sea. They are, at heart, sea creatures, birthed from the sea, married to it like the fishing people who make their livelihood there. Every story you hear about llamas is the same. You see it in books: the poor doomed baby llama getting chomped up by its intemperate parent. On television: the massive tide of scaly llamas falling in a great, majestic herd into the sea below.

Because you’ve seen this story so many times, because you already know the nature and history of llamas, it sometimes shocks you, of course, to see a llama outside of these media spaces. So you forget the llamas that don’t fit the narrative you saw in films, books, television – the ones you heard about in the stories. How To Write Empowering Female Characters. A few months ago I posted an article called Project: Representation asking for people (primarily women and minorities) to provide descriptions of what they thought would be an idealized representation of their race, sex, or other status identifier.

This was in response to two major things. The first was my own uncertainty about my already-established idea of "to write female characters well, just write them like men". This was the idea of characters being defined not by their sex or race, but instead by their personality, career, etc. The potential problem with this was that "have everyone be like white men" might not be the best option, and actual women and ethnic minorities might have some traits that they thought were important or central to their identity. The second issue was one of idealization. This article by Vivienne Chan (click this link it is the basis of the rest of the article) answers a lot of my questions more directly, at least in terms of one person's perspective:

I hate Strong Female Characters. I hate Strong Female Characters.

As someone spends a fair amount of time complaining on the internet that there aren’t enough female heroes out there, this may seem a strange and out of character thing to say. And of course, I love all sorts of female characters who exhibit great resilience and courage. I love it when Angel asks Buffy what’s left when he takes away her weapons and her friends and she grabs his sword between her palms and says “Me”. In Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, I love Zhang Ziyi’s Jen sneering “He is my defeated foe” when asked if she’s related to Chow Yun-Fat's Li Mu Bai. I love Jane Eyre declaring “I care for myself” despite the world’s protracted assault on her self-esteem. But the phrase “Strong Female Character” has always set my teeth on edge, and so have many of the characters who have so plainly been written to fit the bill. I remember watching Shrek with my mother.

“The Princess knew kung-fu! She rolled her eyes. Is Sherlock Holmes strong? 1. 2. Equality. No.