An Introduction to 5-why. Learn how to find root causes of a problem by using 5-why analysis, so you can fix the issues where it matters most.

First in a series of four articles explaining this powerful tool. By Karn G. Bulsuk More information: 5-why Analysis using a Fishbone Diagram, 5-why Analysis using an Excel Spreadsheet Table and The Weaknesses of 5-Why 5-why analysis, used throughout the kaizen concept and in quality control, is a tool to discover the root causes of a problem. More often than not, people fix a problem by dealing with issues that are immediately apparent. For example, suppose we had a tree which was wilting and dying.

Instead, we need to investigate the cause of the wilting. Most people get stuck in the Do-Do-Do-Do cycle, in which they carpet bomb every possible solution with no guarantee that they will fix the true problem, wasting time, effort, and often money. 5-why analysis provides the tool to engage in precision targeting to fix the right problem in one go. Questioning Techniques. Six Thinking Hats. Decisive: The Four Villains of Decision Making. You're probably not as effective at making decisions as you could be.

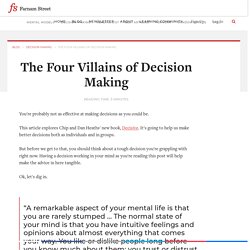

This article explores Chip and Dan Heaths' new book, Decisive. It's going to help us make better decisions both as individuals and in groups. But before we get to that, you should think about a tough decision you're grappling with right now. Having a decision working in your mind as you're reading this post will help make the advice in here tangible. Ok, let's dig in.

“A remarkable aspect of your mental life is that you are rarely stumped … The normal state of your mind is that you have intuitive feelings and opinions about almost everything that comes your way. . — Daniel Kahneman We're quick to jump to conclusions because we give too much weight to the information in front of us and we fail to search for new information, which might disprove our thoughts.

Nobel Prize winning Psychologist Daniel Kahneman called this tendency “what you see is all there is.” We're overconfident. 1. They call this WRAP. What Matters More in Decisions: Analysis or Process? Think of the last major decision your company made.

Maybe it was an acquisition, a large purchase, or perhaps it was whether to launch a new product. Odds are three things went into that decision: (1) It probably relied on the insights of a few key executives; (2) it involved some sort of fact gathering and analysis; and (3) it was likely enveloped in some sort of decision process—whether formal or informal—that translated the analysis into a decision. Now how would you rate the quality of your organization’s strategic decisions? If you’re like most executives, the answer wouldn’t be positive: In a recent McKinsey Quarterly survey of 2,207 executives, only 28 percent said that the quality of strategic decisions in their companies was generally good, 60 percent thought that bad decisions were about as frequent as good ones, and the remaining 12 percent thought good decisions were altogether infrequent.

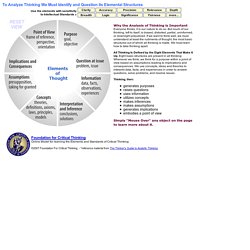

How could it be otherwise? Product launches are frequently behind schedule and over budget. Critical Thinking Model 1. To Analyze Thinking We Must Identify and Question its Elemental Structures Standard: Clarityunderstandable, the meaning can be grasped.

Slow Deciders Make Better Strategists. There are many ways to split people into two groups.

Young and old. Rich and poor. Us and them. The 98% who can do arithmetic and the 3% who cannot. Those who split people into two groups and those who don’t. Then there’s the people who make good competitive-strategy decisions, and those who don’t. It’s not easy to split people into the good/bad strategy decision-makers. What about mindset? Imagine that we can record decision-makers’ solutions to a competitive-strategy problem. I’ve got such a database of people, those who have entered the Top Pricer Tournament. Dozens of Tournament entrants said they were very confident in their strategies after making a fast decision, dozens said they were very confident after a slow decision, and so on. In general, the I-already-knows, confident in their snap judgments, and the Now-I-knows, confident after pondering, tend to be older males.

Understanding the Pareto Principle (The 80/20 Rule) Originally, the Pareto Principle referred to the observation that 80% of Italy’s wealth belonged to only 20% of the population.

More generally, the Pareto Principle is the observation (not law) that most things in life are not distributed evenly. It can mean all of the following things: 20% of the input creates 80% of the result20% of the workers produce 80% of the result20% of the customers create 80% of the revenue20% of the bugs cause 80% of the crashes20% of the features cause 80% of the usageAnd on and on… But be careful when using this idea! First, there’s a common misconception that the numbers 20 and 80 must add to 100 — they don’t! 20% of the workers could create 10% of the result. Also recognize that the numbers don’t have to be “20%” and “80%” exactly.

Wicked Problems. If you work in an organisation that deals with social, commercial or financial planning - or any type of public policy planning - then you've got wicked problems.

You may not call them by this name, but you know what they are. They are those complex, ever changing societal and organisational planning problems that you haven't been able to treat with much success, because they won't keep still. They're messy, devious, and they fight back when you try to deal with them. This paper describes the notion of wicked problems (WPs) as put forward by Rittel & Webber in their landmark article "Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning" (1973). It presents the ten criteria they use to characterise WPS, and describes how General Morphological Analysis (GMA) can be used to model and analyse such problem complexes. Keywords: Wicked problems, general morphological analysis, policy analysis, Horst Rittel. Strategic Planning.