33cdCore. The Institute For Figuring // Where the Wild Things Are. MW: There are knots that are “wild” and others that are “tame.”

Can you tell us what a wild knot is? KM: I would explain it by giving you an example and then saying, “Think like that.” Imagine I take a bunch of beads and we’re going to make a sort of necklace. Now take the first bead and I tie a little trefoil knot inside it. Now next to that I attach another bead, but this time with half the radius and inside that I make a smaller trefoil knot. KM: In the physical science world, wild knots never happen.

MW: Do wild things occur in all dimensions? KM: I am embarrassed to say I don’t know for sure. But let me tell you about another really charming problem. MW: You must have an answer up to a certain number of edges? KM: Eight. MW: For eight edges how many knots are there? KM: For eight equal-length edges, there are eight or nine different knots, apart from the “trivial knot,” and we don’t even know whether it’s eight or nine. KM: It is humbling. Institute For Figuring. Aug 14 Fri Symposium 10am - 5:45pm@ Deakin University, Melbourne Australia This week, IFF directors Margaret and Christine Wertheim are presenting keynotes at the Unruly Techniques Symposium at Deakin University, Melbourne Australia.

- The Institute For Figuring - Now Urbanism Mapping The City. Christian Nold is a German born “artist, designer and educator working to develop new participatory models for communal representation.”

He graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2004 with an MA in Interaction Design and currently teaches at the Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL). In 2001 he wrote Mobile Vulgus, a book which “examined the history of the political crowd and which set the tone for his research into participatory mapping.” In 2008 he edited Emotional Cartography, “a collection of essays from artists, designers, psychogeographers, cultural researchers, futurologists and neuroscientists to explore the political, social and cultural implications of visualising intimate biometric data and emotional experiences using technology.”

The book includes essay by Raqs Media Collective, Marcel van de Drift, Dr Stephen Boyd Davis, Rob van Kranenburg, Sophie Hope and Dr Tom Stafford Bio-mapping as described by Christian Nold Like this: Like Loading... Related About thatfield. Now Urbanism Mapping The City. Developed by not-for-profit We Are What We Do in partnership with Google, Historypin is the largest user-generated archive of historical images and stories.

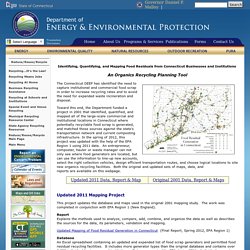

The digital tool operates in the realm of Rephotography, only here historical images, maps, written histories and. Deep Mapping_The Three Landscapes Project. Organics Mapping Project. An Organics Recycling Planning Tool The Connecticut DEEP has identified the need to capture institutional and commercial food scrap in order to increase recycling rates and to avoid the need for expanded waste incineration and disposal.

Toward this end, the Department funded a project in 2001 that identified, quantified, and mapped all of the large-scale commercial and institutional locations in Connecticut where potentially recyclable food scrap is generated, and matched those sources against the state's transportation network and current composting infrastructure. In the spring of 2012, this project was updated with the help of the EPA Region 1 using 2011 data. An entrepreneur, composter, hauler or waste manager can not only see where food generators are located, but can use the information to line-up new accounts, select the right collection vehicles, design efficient transportation routes, and choose logical locations to site new organics recycling facilities.

Shapefiles Report Maps. Deep map. Deep map refers to an emerging practical method of intensive topographical exploration, popularised by author William Least Heat-Moon with his book PrairyErth: A Deep Map. (1991).

A deep map work most often takes the form of engaged documentary writing of literary quality; although it can equally well be done in long-form on radio. It does not preclude the combination of writing with photography and illustration. Its subject is a particular place, usually quite small and limited, and usually rural. Some[who?] Call the approach 'vertical travel writing', while archeologist Michael Shanks compares it to the eclectic approaches of 18th and early 19th century antiquarian topographers or to the psychogeographic excursions of the early Situationist International.[1][2] In North America, it is a method claimed by those interested in bioregionalism.

From Manuscripts to Maps. So far in this workshop we have focused on the individual steps of mapmaking, whether that means creating a map of points or manipulating spatial data.

One of the challenges in creating maps, however, is working through an entire project, from the idea and the source base to the finished map as a class project or publication. The aim of this session to actually work through all of the steps of a real class or research project to gain some experience in seeing a project through all its phases. Creating such project involves thinking through at least these steps: What kind of mapmaking or spatial project would be a significant contribution to my course or my field?

What sources are available for such a project? Preliminaries The following guides may be helpful in in working through such a project. It is important to think through how your data will be structured. Georeferencing is the process of turning place names or addresses into latitudes and longitudes. Potential projects.