Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Nihilism confuses people. "How can you care about anything, or strive for anything, if you believe nothing means anything?" they ask. In return, nihilists point to the assumption of inherent meaning and question that assumption. Do we need existence to mean anything? After all, existence stays out there no matter what we think of it. Nihilists who aren't of the kiddie anarchist variety tend to draw a distinction between nihilism and fatalism. What is nihilism? As a nihilist, I recognize that meaning does not exist. In the same way, I accept that when I die, the most likely outcome will be a cessation of being. Even further, I recognize that there is no golden standard for life. A tree falling in a forest unobserved makes a sound. Many people "feel" marginalized when they think of this. Meaning is the human attempt to mold the world in our own image. This distanced mentality further affirms our tendency to find the world alienating to our consciousness. Nihilism reverses this process.

Belief in Nothing

Thoughts Arguments and Rants » Blog Archive » Philosophy in Questionable Taste

Cornell students obviously have too much time on their hands. (And very soon I’ll be able to do something about that…) Back when I was a wee grad student, one of the jokes circulating the internet, and eventually stuck to the wall of the grad ‘office’ concerned the putative causes of death of various philosophers. In a similar spirit, Cornell students have started work on break-up lines of the philosophers. Here’s the list (mostly below the fold) Paul Kelleher sent me, along with attributions. The Teleologist: We aren’t meant for each other.

Portal:Philosophy

Philosophy of religion is a branch of philosophy concerned with questions regarding religion, including the nature and existence of God, the examination of religious experience, analysis of religious vocabulary and texts, and the relationship of religion and science.[1] It is an ancient discipline, being found in the earliest known manuscripts concerning philosophy, and relates to many other branches of philosophy and general thought, including metaphysics, logic, and history.[2] Philosophy of religion is frequently discussed outside of academia through popular books and debates, mostly regarding the existence of God and problem of evil. The philosophy of religion differs from religious philosophy in that it seeks to discuss questions regarding the nature of religion as a whole, rather than examining the problems brought forth by a particular belief system. It is designed such that it can be carried out dispassionately by those who identify as believers or non-believers.[3] [edit] Aquinas

Philosophy of religion is a branch of philosophy concerned with questions regarding religion, including the nature and existence of God, the examination of religious experience, analysis of religious vocabulary and texts, and the relationship of religion and science.[1] It is an ancient discipline, being found in the earliest known manuscripts concerning philosophy, and relates to many other branches of philosophy and general thought, including metaphysics, logic, and history.[2] Philosophy of religion is frequently discussed outside of academia through popular books and debates, mostly regarding the existence of God and problem of evil. The philosophy of religion differs from religious philosophy in that it seeks to discuss questions regarding the nature of religion as a whole, rather than examining the problems brought forth by a particular belief system. It is designed such that it can be carried out dispassionately by those who identify as believers or non-believers.[3] [edit] Aquinas

Philosophy of religion

Philosophy of mind

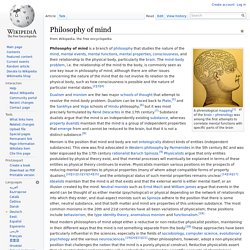

A phrenological mapping[1] of the brain – phrenology was among the first attempts to correlate mental functions with specific parts of the brain Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the nature of the mind, mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness, and their relationship to the physical body, particularly the brain. The mind–body problem, i.e. the relationship of the mind to the body, is commonly seen as one key issue in philosophy of mind, although there are other issues concerning the nature of the mind that do not involve its relation to the physical body, such as how consciousness is possible and the nature of particular mental states.[2][3][4] Mind–body problem[edit] Our perceptual experiences depend on stimuli that arrive at our various sensory organs from the external world, and these stimuli cause changes in our mental states, ultimately causing us to feel a sensation, which may be pleasant or unpleasant. Arguments for dualism[edit]

A phrenological mapping[1] of the brain – phrenology was among the first attempts to correlate mental functions with specific parts of the brain Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the nature of the mind, mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness, and their relationship to the physical body, particularly the brain. The mind–body problem, i.e. the relationship of the mind to the body, is commonly seen as one key issue in philosophy of mind, although there are other issues concerning the nature of the mind that do not involve its relation to the physical body, such as how consciousness is possible and the nature of particular mental states.[2][3][4] Mind–body problem[edit] Our perceptual experiences depend on stimuli that arrive at our various sensory organs from the external world, and these stimuli cause changes in our mental states, ultimately causing us to feel a sensation, which may be pleasant or unpleasant. Arguments for dualism[edit]

Western Philosophy

Part of Nietzsche’s problem with history, science, and the knowledge drive in general is that these activities typically presuppose that "knowing" is possible, and that truth is more valuable than untruth, or appearance. It is supposed that there is another world, one free from our perceptions, which can be known if we can find an objectifying lens through which the real nature of things, i.e. inherent properties, things-in-themselves, essences, can be understood. Nietzsche sees most endeavors concerned with discovering the truth as attempts to separate the knower from the known in such a way that they can separate their perceptions (the way the world seems) from the perceived object (an entity that has an existence free from what we bring to the word.) With this separation of the world into "the world of mere appearances" and the "real world," objects are seen as things-in-themselves, with inherent meanings that are non-revisable, objective, and universal ("The Philosopher" 133).

Part of Nietzsche’s problem with history, science, and the knowledge drive in general is that these activities typically presuppose that "knowing" is possible, and that truth is more valuable than untruth, or appearance. It is supposed that there is another world, one free from our perceptions, which can be known if we can find an objectifying lens through which the real nature of things, i.e. inherent properties, things-in-themselves, essences, can be understood. Nietzsche sees most endeavors concerned with discovering the truth as attempts to separate the knower from the known in such a way that they can separate their perceptions (the way the world seems) from the perceived object (an entity that has an existence free from what we bring to the word.) With this separation of the world into "the world of mere appearances" and the "real world," objects are seen as things-in-themselves, with inherent meanings that are non-revisable, objective, and universal ("The Philosopher" 133).

Epistemology

Hidden musical code found written into Plato's texts

"Plato’s books played a major role in founding Western culture, but they are mysterious and end in riddles," said Dr. Jay Kennedy of University of Manchester's Faculty of Life Sciences. Those riddles are finally being unwound, thanks to Kennedy's thorough five-year study of Plato's best-known work, "The Republic". "It is a long and exciting story, but basically I cracked the code. I have shown rigorously that the books do contain codes and symbols and that unraveling them reveals the hidden philosophy of Plato." So what great wisdom does the secret message reveal? Plato was influenced by Pythagoras, another ancient Greek philosopher and mathematician who is perhaps best known for discovering the Pythagorean Theorem. Kennedy discovered that Plato had placed clusters of words related to music in his master work, which can be broken into 12 equal sections — a pattern he suspected was related to the twelve notes of the Greek musical scale.

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with reality, existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language.[1][2] Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational argument.[3] In more casual speech, by extension, "philosophy" can refer to "the most basic beliefs, concepts, and attitudes of an individual or group".[4] The word "philosophy" comes from the Ancient Greek φιλοσοφία (philosophia), which literally means "love of wisdom".[5][6][7] The introduction of the terms "philosopher" and "philosophy" has been ascribed to the Greek thinker Pythagoras.[8] Areas of inquiry Philosophy is divided into many sub-fields. Epistemology Epistemology is concerned with the nature and scope of knowledge,[11] such as the relationships between truth, belief, and theories of justification. Rationalism is the emphasis on reasoning as a source of knowledge. Logic

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with reality, existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language.[1][2] Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational argument.[3] In more casual speech, by extension, "philosophy" can refer to "the most basic beliefs, concepts, and attitudes of an individual or group".[4] The word "philosophy" comes from the Ancient Greek φιλοσοφία (philosophia), which literally means "love of wisdom".[5][6][7] The introduction of the terms "philosopher" and "philosophy" has been ascribed to the Greek thinker Pythagoras.[8] Areas of inquiry Philosophy is divided into many sub-fields. Epistemology Epistemology is concerned with the nature and scope of knowledge,[11] such as the relationships between truth, belief, and theories of justification. Rationalism is the emphasis on reasoning as a source of knowledge. Logic

Philosophy

Metaphysics is a traditional branch of philosophy concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world that encompasses it,[1] although the term is not easily defined.[2] Traditionally, metaphysics attempts to answer two basic questions in the broadest possible terms:[3] Ultimately, what is there?What is it like? Prior to the modern history of science, scientific questions were addressed as a part of metaphysics known as natural philosophy. Etymology[edit] However, once the name was given, the commentators sought to find intrinsic reasons for its appropriateness. There is a widespread use of the term in current popular literature which replicates this understanding, i.e. that the metaphysical equates to the non-physical: thus, "metaphysical healing" means healing by means of remedies that are not physical.[8] Central questions[edit] Cosmology and cosmogony[edit] Cosmogony deals specifically with the origin of the universe. Determinism and free will[edit] [edit] [edit] [edit]

Metaphysics is a traditional branch of philosophy concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world that encompasses it,[1] although the term is not easily defined.[2] Traditionally, metaphysics attempts to answer two basic questions in the broadest possible terms:[3] Ultimately, what is there?What is it like? Prior to the modern history of science, scientific questions were addressed as a part of metaphysics known as natural philosophy. Etymology[edit] However, once the name was given, the commentators sought to find intrinsic reasons for its appropriateness. There is a widespread use of the term in current popular literature which replicates this understanding, i.e. that the metaphysical equates to the non-physical: thus, "metaphysical healing" means healing by means of remedies that are not physical.[8] Central questions[edit] Cosmology and cosmogony[edit] Cosmogony deals specifically with the origin of the universe. Determinism and free will[edit] [edit] [edit] [edit]

Metaphysics

Analytic philosophy (sometimes analytical philosophy) is a style of philosophy that came to dominate English-speaking countries in the 20th century. In the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Scandinavia, Australia, and New Zealand, the vast majority of university philosophy departments identify themselves as "analytic" departments.[1] The term "analytic philosophy" can refer to: A broad philosophical tradition[2][3] characterized by an emphasis on clarity and argument (often achieved via modern formal logic and analysis of language) and a respect for the natural sciences.[4][5][6]The more specific set of developments of early 20th-century philosophy that were the historical antecedents of the broad sense: e.g., the work of Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, G. In this latter, narrower sense, analytic philosophy is identified with specific philosophical commitments (many of which are rejected by contemporary analytic philosophers), such as: History[edit] Logical positivism[edit]

Analytic philosophy

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Western Philosophers

Welcome to my collection of online philosophy resources. If you are stuck in a frame, click here to escape. If you are a frequent visitor, press reload or refresh on occasion to be sure that you are viewing the most recent version of the page, not the version cached on your hard drive from your last visit. I've marked recommended sites with a red star . When the whole file loads, use the search command on your browser to find items by keyword. To register to receive an email announcement whenever this page is revised, see the bottom of this file. If speed is a problem, try one of the mirror sites in Germany (München, single-file version) or Italy (Bari, single-file version), or Italy (Bari, multi-file version). About this guide. I welcome URLs for inclusion, notice of broken links, and suggestions and comments of all kinds. If you're interested in guides like this to disciplines other than philosophy, see my list of lists of them.

Welcome to my collection of online philosophy resources. If you are stuck in a frame, click here to escape. If you are a frequent visitor, press reload or refresh on occasion to be sure that you are viewing the most recent version of the page, not the version cached on your hard drive from your last visit. I've marked recommended sites with a red star . When the whole file loads, use the search command on your browser to find items by keyword. To register to receive an email announcement whenever this page is revised, see the bottom of this file. If speed is a problem, try one of the mirror sites in Germany (München, single-file version) or Italy (Bari, single-file version), or Italy (Bari, multi-file version). About this guide. I welcome URLs for inclusion, notice of broken links, and suggestions and comments of all kinds. If you're interested in guides like this to disciplines other than philosophy, see my list of lists of them.

Guide to Philosophy on the Internet (Suber)

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The school of analytic philosophy has dominated academic philosophy in various regions, most notably Great Britain and the United States, since the early twentieth century. It originated around the turn of the twentieth century as G. E. Moore and Bertrand Russell broke away from what was then the dominant school in the British universities, Absolute Idealism. Many would also include Gottlob Frege as a founder of analytic philosophy in the late 19th century, and this controversial issue is discussed in section 2c. Analytic philosophy underwent several internal micro-revolutions that divide its history into five phases. During the 1960s, criticism from within and without caused the analytic movement to abandon its linguistic form. Even in its earlier phases, analytic philosophy was difficult to define in terms of its intrinsic features or fundamental philosophical commitments. Table of Contents 1. “It was towards the end of 1898,” wrote Bertrand Russell, 2. a. b. c. d. 3. a. b. 4. a. b.

Analytic Philosophy

Philosophy Pages

The Socratic Method

The Socratic Method:Teaching by Asking Instead of by Tellingby Rick Garlikov The following is a transcript of a teaching experiment, using the Socratic method, with a regular third grade class in a suburban elementary school. I present my perspective and views on the session, and on the Socratic method as a teaching tool, following the transcript. The experiment was to see whether I could teach these students binary arithmetic (arithmetic using only two numbers, 0 and 1) only by asking them questions. I had one prior relationship with this class. When I got to the classroom for the binary math experiment, students were giving reports on famous people and were dressed up like the people they were describing. "But what I am really here for today is to try an experiment with you. 1) "How many is this?" 2) "Who can write that on the board?" 3) Who can write ten another way? 4) Another way? 5) Another way? 2 x 5 [inspired by the last idea] 7) One more? X [Roman numeral] 14) Which, nine or ten?

Morality in the Real World (podcast index)

Morality in the Real World is a series of dialogues about what kinds of moral value do and do not exist in the natural world, how we can examine these issues carefully, and how we can (really) make the world a better place. You can join in, too. Every 5 episodes we answer audience questions about what we’ve discussed so far. If you’d like us to respond, leave a comment on the page of the relevant episode, or leave a voicemail at 413-723-0175. You can listen to all episodes at archive.org, or subscribe in iTunes or with RSS. Episodes are best enjoyed in order, but it’s not strictly necessary. Season One 01: Introduction [mp3] 02: God is Not the Ground for Morality [mp3] 03: Alph and Betty on a Distant Planet [mp3] 04: The Scrooge Problem [mp3] 05: Questions and Answers #1 [mp3] 06: Alph and Preserving Pandora [mp3] 07: Desire Fulfillment Does Not Have Intrinsic Value [mp3] 08: A Harmony of Desires [mp3] 09: How to Measure Desires [mp3] 10: Questions and Answers #2 [mp3] Season Two (more to come)

What is Stoicism and How Can it Turn your Life to Solid Gold?

A few weeks ago, I got a really interesting email from a guy in Norway that said something like, “Hey Mr. MM.. What you are preaching is Pure Stoicism, with a great twist and perception on today’s world … I love it!!” * “Stoicism?” But it turns out I had fallen into a common misconception. From reading the book, I learned that Stoicism was actually a shockingly advanced old philosophy that found many followers in ancient Rome. Stoicism, in short, is a series of mental techniques and ways of life that allow you to decrease and then virtually eliminate all negative emotions such as anger, fear, anxiety, and dissatisfaction, while simultaneously building up a tide of pure Joy inside you that eventually starts to make you jump around and boogie at unexpected moments, and occasionally shout out “AHH YEAH!!” Sounds pretty good, doesn’t it? So let’s see what it’s all about. The core of the philosophy seems to be this: To have a good and meaningful life, you need to overcome your insatiability.

An Essay by Einstein -- The World As I See It - StumbleUpon

40 Belief-Shaking Remarks From a Ruthless Nonconformist | Raptitude.com - StumbleUpon

Platos "The Allegory of the Cave": A Summary - StumbleUpon

Diogenes The Dog

Philagora, ressources culturelles

Logical Paradoxes

Philosophy of mind

Philosophical teaching will get students thinking for themselves again | Teacher Network | Guardian Professional

The Partially Examined Life | A Philosophy Podcast and Philosophy Blog

Logical Paradoxes

Logical Fallacies

Philosophy of religion is a branch of philosophy concerned with questions regarding religion, including the nature and existence of God, the examination of religious experience, analysis of religious vocabulary and texts, and the relationship of religion and science.[1] It is an ancient discipline, being found in the earliest known manuscripts concerning philosophy, and relates to many other branches of philosophy and general thought, including metaphysics, logic, and history.[2] Philosophy of religion is frequently discussed outside of academia through popular books and debates, mostly regarding the existence of God and problem of evil. The philosophy of religion differs from religious philosophy in that it seeks to discuss questions regarding the nature of religion as a whole, rather than examining the problems brought forth by a particular belief system. It is designed such that it can be carried out dispassionately by those who identify as believers or non-believers.[3] [edit] Aquinas

Philosophy of religion

Philosophy of religion is a branch of philosophy concerned with questions regarding religion, including the nature and existence of God, the examination of religious experience, analysis of religious vocabulary and texts, and the relationship of religion and science.[1] It is an ancient discipline, being found in the earliest known manuscripts concerning philosophy, and relates to many other branches of philosophy and general thought, including metaphysics, logic, and history.[2] Philosophy of religion is frequently discussed outside of academia through popular books and debates, mostly regarding the existence of God and problem of evil. The philosophy of religion differs from religious philosophy in that it seeks to discuss questions regarding the nature of religion as a whole, rather than examining the problems brought forth by a particular belief system. It is designed such that it can be carried out dispassionately by those who identify as believers or non-believers.[3] [edit] Aquinas

Philosophy of religion

A phrenological mapping[1] of the brain – phrenology was among the first attempts to correlate mental functions with specific parts of the brain Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the nature of the mind, mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness, and their relationship to the physical body, particularly the brain. The mind–body problem, i.e. the relationship of the mind to the body, is commonly seen as one key issue in philosophy of mind, although there are other issues concerning the nature of the mind that do not involve its relation to the physical body, such as how consciousness is possible and the nature of particular mental states.[2][3][4] Mind–body problem[edit] Our perceptual experiences depend on stimuli that arrive at our various sensory organs from the external world, and these stimuli cause changes in our mental states, ultimately causing us to feel a sensation, which may be pleasant or unpleasant. Arguments for dualism[edit]

A phrenological mapping[1] of the brain – phrenology was among the first attempts to correlate mental functions with specific parts of the brain Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the nature of the mind, mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness, and their relationship to the physical body, particularly the brain. The mind–body problem, i.e. the relationship of the mind to the body, is commonly seen as one key issue in philosophy of mind, although there are other issues concerning the nature of the mind that do not involve its relation to the physical body, such as how consciousness is possible and the nature of particular mental states.[2][3][4] Mind–body problem[edit] Our perceptual experiences depend on stimuli that arrive at our various sensory organs from the external world, and these stimuli cause changes in our mental states, ultimately causing us to feel a sensation, which may be pleasant or unpleasant. Arguments for dualism[edit]

Part of Nietzsche’s problem with history, science, and the knowledge drive in general is that these activities typically presuppose that "knowing" is possible, and that truth is more valuable than untruth, or appearance. It is supposed that there is another world, one free from our perceptions, which can be known if we can find an objectifying lens through which the real nature of things, i.e. inherent properties, things-in-themselves, essences, can be understood. Nietzsche sees most endeavors concerned with discovering the truth as attempts to separate the knower from the known in such a way that they can separate their perceptions (the way the world seems) from the perceived object (an entity that has an existence free from what we bring to the word.) With this separation of the world into "the world of mere appearances" and the "real world," objects are seen as things-in-themselves, with inherent meanings that are non-revisable, objective, and universal ("The Philosopher" 133).

Epistemology

Part of Nietzsche’s problem with history, science, and the knowledge drive in general is that these activities typically presuppose that "knowing" is possible, and that truth is more valuable than untruth, or appearance. It is supposed that there is another world, one free from our perceptions, which can be known if we can find an objectifying lens through which the real nature of things, i.e. inherent properties, things-in-themselves, essences, can be understood. Nietzsche sees most endeavors concerned with discovering the truth as attempts to separate the knower from the known in such a way that they can separate their perceptions (the way the world seems) from the perceived object (an entity that has an existence free from what we bring to the word.) With this separation of the world into "the world of mere appearances" and the "real world," objects are seen as things-in-themselves, with inherent meanings that are non-revisable, objective, and universal ("The Philosopher" 133).

Epistemology

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with reality, existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language.[1][2] Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational argument.[3] In more casual speech, by extension, "philosophy" can refer to "the most basic beliefs, concepts, and attitudes of an individual or group".[4] The word "philosophy" comes from the Ancient Greek φιλοσοφία (philosophia), which literally means "love of wisdom".[5][6][7] The introduction of the terms "philosopher" and "philosophy" has been ascribed to the Greek thinker Pythagoras.[8] Areas of inquiry Philosophy is divided into many sub-fields. Epistemology Epistemology is concerned with the nature and scope of knowledge,[11] such as the relationships between truth, belief, and theories of justification. Rationalism is the emphasis on reasoning as a source of knowledge. Logic

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with reality, existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language.[1][2] Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational argument.[3] In more casual speech, by extension, "philosophy" can refer to "the most basic beliefs, concepts, and attitudes of an individual or group".[4] The word "philosophy" comes from the Ancient Greek φιλοσοφία (philosophia), which literally means "love of wisdom".[5][6][7] The introduction of the terms "philosopher" and "philosophy" has been ascribed to the Greek thinker Pythagoras.[8] Areas of inquiry Philosophy is divided into many sub-fields. Epistemology Epistemology is concerned with the nature and scope of knowledge,[11] such as the relationships between truth, belief, and theories of justification. Rationalism is the emphasis on reasoning as a source of knowledge. Logic

Philosophy

Metaphysics is a traditional branch of philosophy concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world that encompasses it,[1] although the term is not easily defined.[2] Traditionally, metaphysics attempts to answer two basic questions in the broadest possible terms:[3] Ultimately, what is there?What is it like? Prior to the modern history of science, scientific questions were addressed as a part of metaphysics known as natural philosophy. Etymology[edit] However, once the name was given, the commentators sought to find intrinsic reasons for its appropriateness. There is a widespread use of the term in current popular literature which replicates this understanding, i.e. that the metaphysical equates to the non-physical: thus, "metaphysical healing" means healing by means of remedies that are not physical.[8] Central questions[edit] Cosmology and cosmogony[edit] Cosmogony deals specifically with the origin of the universe. Determinism and free will[edit] [edit] [edit] [edit]

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is a traditional branch of philosophy concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world that encompasses it,[1] although the term is not easily defined.[2] Traditionally, metaphysics attempts to answer two basic questions in the broadest possible terms:[3] Ultimately, what is there?What is it like? Prior to the modern history of science, scientific questions were addressed as a part of metaphysics known as natural philosophy. Etymology[edit] However, once the name was given, the commentators sought to find intrinsic reasons for its appropriateness. There is a widespread use of the term in current popular literature which replicates this understanding, i.e. that the metaphysical equates to the non-physical: thus, "metaphysical healing" means healing by means of remedies that are not physical.[8] Central questions[edit] Cosmology and cosmogony[edit] Cosmogony deals specifically with the origin of the universe. Determinism and free will[edit] [edit] [edit] [edit]

Metaphysics

Welcome to my collection of online philosophy resources. If you are stuck in a frame, click here to escape. If you are a frequent visitor, press reload or refresh on occasion to be sure that you are viewing the most recent version of the page, not the version cached on your hard drive from your last visit. I've marked recommended sites with a red star . When the whole file loads, use the search command on your browser to find items by keyword. To register to receive an email announcement whenever this page is revised, see the bottom of this file. If speed is a problem, try one of the mirror sites in Germany (München, single-file version) or Italy (Bari, single-file version), or Italy (Bari, multi-file version). About this guide. I welcome URLs for inclusion, notice of broken links, and suggestions and comments of all kinds. If you're interested in guides like this to disciplines other than philosophy, see my list of lists of them.

Guide to Philosophy on the Internet (Suber)

Welcome to my collection of online philosophy resources. If you are stuck in a frame, click here to escape. If you are a frequent visitor, press reload or refresh on occasion to be sure that you are viewing the most recent version of the page, not the version cached on your hard drive from your last visit. I've marked recommended sites with a red star . When the whole file loads, use the search command on your browser to find items by keyword. To register to receive an email announcement whenever this page is revised, see the bottom of this file. If speed is a problem, try one of the mirror sites in Germany (München, single-file version) or Italy (Bari, single-file version), or Italy (Bari, multi-file version). About this guide. I welcome URLs for inclusion, notice of broken links, and suggestions and comments of all kinds. If you're interested in guides like this to disciplines other than philosophy, see my list of lists of them.

Guide to Philosophy on the Internet (Suber)