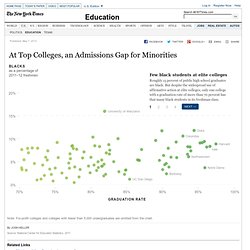

At Elite Colleges, an Admissions Gap for Minorities - Interactive Feature. Few black students at elite colleges Roughly 15 percent of public high school graduates are black.

But despite the widespread use of affirmative action at elite colleges, only one college with a graduation rate of more than 70 percent has that many black students in its freshman class. Stuck at the bottom Many more black students attend colleges with low graduation rates, shown in red. While young blacks are almost as likely as young whites to go to college, they are half as likely to have a degree. Hispanics go to two-year colleges Hispanics are more likely than any other group to attend community colleges, which tend to have more dropouts. Asians outperform Asians represent only 5 percent of public high school graduates, but they make up a greater proportion of the freshman class at nearly every college with a graduation rate of more than 80 percent. Whites are more evenly distributed Whites are overrepresented at most colleges with graduation rates of more than half. Segregation Prominent in Schools, Study Finds. Photo The United States is increasingly a multiracial society, with white students accounting for just over half of all students in public schools, down from four-fifths in 1970.

Yet whites are still largely concentrated in schools with other whites, leaving the largest minority groups — black and Latino students — isolated in classrooms, according to a new analysis of Department of Education data. The report showed that segregation is not limited to race: blacks and Latinos are twice as likely as white or Asian students to attend schools with a substantial majority of poor children. Across the country, 43 percent of Latinos and 38 percent of blacks attend schools where fewer than 10 percent of their classmates are white, according to the report, released on Wednesday by the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles. Segregation of Latino students is most pronounced in California, New York and Texas.

“Is it possible to learn calculus in a segregated school? Is Segregation Back in U.S. Public Schools? - Room for Debate. Emily Berl for the New York Times Last week marked the 58th anniversary of the Brown v.

Board of Education decision, which declared racial segregation of public schools unconstitutional. But segregation, now due largely to geography, still remains an issue for most school systems, from New York City to Charlotte, N.C., and beyond. In his article in The Sunday Review, David L. Kirp, the author of “Kids First,” said that “desegregation is effectively dead.” How can we integrate public schools when neighborhoods have become more segregated? At Explore Charter School, a Portrait of Segregated Education. Floriande Augustin, a first-year teacher at the school, invited students to share their choices.

Hands waved for attention. One girl said it was when she got a cat, though she was unsure why. Another selected a car crash. A third brought up the time when her cousin got shot and “it was positive because he felt his life was crazy and he went to college so he couldn’t get shot anymore.” The lesson detoured into Martin Luther King Jr. and his turning points. The students scribbled notes. In the broad resegregation of the nation’s schools that has transpired over recent decades, New York’s public-school system looms as one of the most segregated. About 650 of the nearly 1,700 schools in the system have populations that are 70 percent a single race, a New York Times analysis of schools data for the 2009-10 school year found; more than half the city’s schools are at least 90 percent black and Hispanic.

The school’s enrollment is even more racially lopsided than its catchment area. As Ms. Mr. Segregation in New York City’s Public Schools - Graphic. Diversity Debate Engulfs Hunter High in Manhattan. But instead, the school is in turmoil, with much of the faculty in an uproar over the resignation of a popular principal, the third in five years.

In her departure speech to teachers in late June, the principal cited several reasons for her decision, including tensions over a lack of diversity at the school, which had been the subject of a controversial graduation address the day before by one of the school’s few African-American students. Hours after the principal’s address, a committee of Hunter High teachers that included Ms. Kagan’s brother, Irving, read aloud a notice of no confidence to the president of , who ultimately oversees the high school, one of the most prestigious public schools in the nation. The events fanned a long-standing disagreement between much of the high school faculty and the administration of Hunter College over the use of a single, teacher-written test for admission to the school, which has grades 7 through 12. Then he shocked his audience. In a sense, Mr. Diversity in the Classroom.