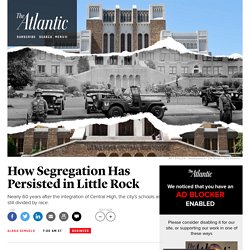

How Segregation Has Persisted in Little Rock. We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place.

Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. –Brown v. Board of Education, 1954 LITTLE ROCK—In the 1960s, while other middle-school students were worrying about letter jackets or boyfriends or saddle shoes, LaVerne Bell-Tolliver was simply trying to stay sane. Bell-Tolliver’s parents had volunteered her to integrate Forest Heights Junior High in Little Rock in 1961, and as the only black student in a crush of white ones, she was always on guard. “My realm was surviving,” she told me recently, in a café in Little Rock. Bell-Tolliver looks at Little Rock schools now, though, and wonders if her years of hell were all in vain.

And those separate schools are not at all equal. “It’s still unequal,” Bell-Tolliver told me. Today, those who oppose integration are still fighting it, but in less overt ways. That wasn’t the only discrepancy. Bell-Tolliver saw it in her own neighborhood. Emory Douglas' art takes him from Black Panthers to the Walker. Artist Emory Douglas has been called the "Norman Rockwell of the ghetto.

" Douglas was the Black Panther Party's "minister of culture" for 13 years, during which time he oversaw the art for the movement's official weekly newspaper. He used his graphic design skills to create provocative images that criticized the police and the government while drawing attention to the poor and oppressed. This week Douglas was in the Twin Cities for a talk at Penumbra Theatre in St. Paul, and his work is currently on display at the Walker Art Center as part of "Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia. " Douglas said for him, the measure of success was simply being able to continue what he was doing. "It wasn't about being patted on the back," he said. Formed in 1966 by Huey P. The Man Behind the Art of the Black Panther Party: Emory Douglas Tells His Story.

PHOTOS: Menus From Old Harlem Hot Spots Show Area's Foodie History - Central Harlem - DNAinfo.com New York. HARLEM — The Harlem food scene is nothing new.

In the 1920s, you could get a filet mignon at the Cotton Club for $2.25. If you wanted something fancier you had to go to Frank’s for a $4.50 T-bone with French fries and then walk across the street to Club Baby Grand and listen to the "greatest singing stars of stage, screen, and radio. " A collection of old menus from the restaurants and nightclubs of Harlem’s past from the Schomburg Center of Research in Black Culture give a glimpse into what the neighborhood used to look like. “The Cotton Club era represents a time where Harlem was a major tourist destination,” said historian Michael Henry Adams. “These earlier restaurants often would cater to outsiders, many of whom where white and often times had some kind of theme or association with southern cuisines.” The Cotton Club, which was on West 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue back then, had a policy of only hiring African American entertainers, waiters, and staff.

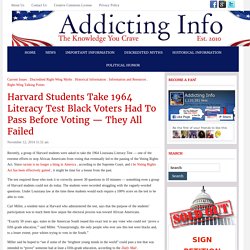

Map of 73 Years of Lynchings. Addicting Info – Harvard Students Take 1964 Literacy Test Black Voters Had To Pass Before Voting — They All Failed. Recently, a group of Harvard students were asked to take the 1964 Louisiana Literacy Test — one of the extreme efforts to stop African Americans from voting that eventually led to the passing of the Voting Rights Act.

Since racism is no longer a thing in America , according to the Supreme Court, and t he Voting Rights Act has been effectively gutted , it might be time for a lesson from the past. The test required those who took it to correctly answer 30 questions in 10 minutes — something even a group of Harvard students could not do today. The students were recorded struggling with the vaguely-worded questions. Under Louisiana law at the time these students would each require a 100% score on the test to be able to vote. Carl Miller, a resident tutor at Harvard who administered the test, says that the purpose of the students’ participation was to teach them how unjust the electoral process was toward African Americans. “Louisiana’s literacy test was designed to be failed.

Slavery. The Mark E. Mitchell Collection.