The Dream as Dream Text: Sor Juana as Creature of Fiction or Creature of Reality, with Deborah Conway de Prieto, Ph.D. – September – 24 – JCF Mythological RoundTable® Ojai – Mythosophia. Women of the Page: Convent Culture in the Early Modern Spanish World. Across the Spanish Empire, women from all walks of life entered convents, and the institutions they inhabited replicated the social stratifications of the secular world.

The wealthiest convents, such as Madrid’s Descalzas Reales (featured here), admitted only women from the Spanish royal family and upper nobility, whereas the poorest beaterios (houses for women who took simple, or non-binding religious vows) accepted divorcees, former prostitutes, and street peddlers. Nuns also established clear social hierarchies within their specific institutions. These hierarchies were particularly evident in convents – especially those whose residents included servants and slaves – in the New World, where skin color determined a woman’s station and even the color of her veil. At the top of the conventual order were professed, or black-veiled nuns: well-off European and criolla women (those of European ancestry) with sizable dowries.

Before Sister Wendy Beckett, Italian Renaissance Nuns Shaped Art History. As they slowly emerge, artworks by nuns have been summarized by a derisive umbrella term: Nonnenarbeiten (German for “nuns’ works”).

“We would never assign a Sacra conversatione [a type of devotional painting depicting the Virgin and Child] by Fra Angelico and a portrait by Fra Filippo Lippi to the same genre simply because both happen to have been painted by friars,” art historian Jeffrey F. Hamburger writes in his book Nuns as Artists (1997). “Far from providing an apt, let alone productive, characterization of the images it seeks to define, Nonnenarbeit stands by definition for deficiency: a lack of both skill and sophistication.”

The term also neglects that these devotional images were, in their time, considered intellectual arts. Convents have always supported themselves with a number of craft enterprises, the real moneymakers being embroidery and textile work. History's "worst" nun on Behance. Before Sister Wendy Beckett, Italian Renaissance Nuns Shaped Art History. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s 366th Birthday. Conserving Dürer’s Triumphal Arch: Getting the big picture – The British Museum Blog.

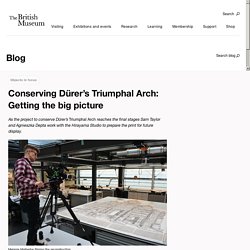

Melanie Malherbe filming the reconstruction.

Once we had finished washing all of the sheets (which you can read about in the previous blog) we laid them out to get an impression of what the print looked like as a whole. A few sheets were then singled out for more cleaning due to ingrained dirt. Having established a tradition of experimenting with unusual tools, we used very fine cosmetic brushes (intended for cleaning nose pores on humans) that are softer than a squirrel’s tail. Conservators Jude Rayner, Caroline Barry and Sam Taylor comparing sheets of the Triumphal Arch. The washing process presented a good opportunity to reduce some of the creases by gently brushing the wet sheets flat between thin, non-woven polyester layers.

Re-sizing one of the sheets. To help strengthen the paper after washing and to make sure it is fit for study and viewing for at least a century, we applied a sizing solution through protective tissue with a soft goat’s hair brush, ensuring an even application. Sor Juana. Vistas: Gallery: Biombo Portraying a View of the Palace of the Viceroy in Mexico City. Women in European History. Dr.

Jennifer Palmer 23 March 2017. Relig[io]sa gero[ni]ma Sor Juana Ines de la [Cruz] ... - JCB Archive of Early American Images. Youtube. Neptuno Alegórico , reproducción. Arco Triunfal para recibir al Marqués de... - Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Fama y obras póstumas - Universitätsbibliothek Bielefeld: Digitale Sammlungen. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Religion, Art, and Feminism - Pamela Kirk, Pamela Kirk Rappaport - Google Books. 18743 43668 1 PB. Book review: “Sor Juana’s Love Poems/Poemas De Amor” by Sor Juana Ines de La Cruz, translated by Joan Larkin & Jaime Manrique. On one of the first pages of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Dolly Oblonsky is packing to leave her womanizing husband and is described as taking something out of an open chest of drawers.

That’s how one translation has it, but, while researching a story about translations for the Chicago Tribune, I had occasion to compare this scene in six English language versions of the masterpiece. What I found was that other translators identified this piece of furniture differently — variously, as an open bureau, as an open wardrobe, and as an open chiffonier. In the original Russian, it was the same word, but it was transformed into English in these four different ways. Translation is always a dicey proposition. Talk to translators, and they’ll tell you that it’s an art, not a science. And, if one Russian word for a piece of furniture can result in such varied responses by translators, how much greater variance is implicit in the translation of poetry?

“Beautiful girl” The earthiest of language “To bed” 2011 Conference on Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Her Work, Colonial Mexico, and Spain's Golden Age. Wardman Library databases & journals for off-campus access. Sor Juana Fecit: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and the Art of Miniature Painting on JSTOR. Las monjas coronadas. Vida conventual femenina. SLC "Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz" by Xánath Caraza. Portrait of Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz.