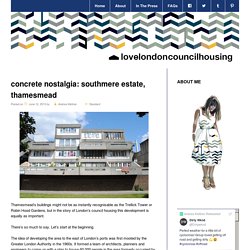

Concrete nostalgia: Southmere estate, Thamesmead. Thamesmead’s buildings might not be as instantly recognisable as the Trellick Tower or Robin Hood Gardens, but in the story of London’s council housing this development is equally as important.

There’s so much to say. Let’s start at the beginning. The idea of developing the area to the east of London’s ports was first mooted by the Greater London Authority in the 1960s. It formed a team of architects, planners and engineers to come up with a plan to house 60,000 people in the area formerly occupied by the Royal Arsenal – riverside marshland with lots of abandoned buildings. Here are two model shots of what they came up with. Artifical lakes and recreational areas would be surrounded by low- and high-rise housing, schools, shops and health centres, all linked by pedestrian pathways at different levels.

The architects tried to design out problems that plagued many post-war estates – trying to encourage contact between neighbours. A public poll voted for the name Thamesmead. Want to know more? Thamesmead - Hidden London. Once dubbed the ‘town of the twenty-first century’ Thamesmead is a vast housing estate, with some peripheral industry, situated on former marshland between Woolwich and Erith The River Thames here makes its most northerly excursion within Greater London, so Thamesmead is on the same latitude as Westminster.

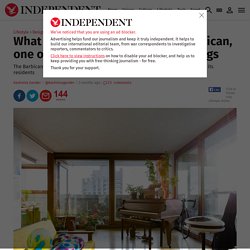

Its name was the winning entry in a newspaper competition, although it has been suggested that the planners always had that name in mind – and they simply waited for a competition entrant to come up with it too. What it's like to live inside the Barbican, one of London's most iconic buildings. Few of us would describe our home as a "concrete oasis amidst the yin-yang complexion of living in the City" but those are the exact words of one resident of the Barbican towers in the City of London.

"Bustling with City workers during the week, then a relative ghost town at weekends. [It's] the best of both worlds," adds the resident, only identified as Nigel. That is the pleasure afforded to those lucky (and frankly, wealthy) enough to live inside an icon of modern archiecture. Nigel is among tenants to be featured in Residents: Inside the Iconic Barbican Estate, a new book which gives an inight into the lives inside 22 of the homes.

Designed by architects Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, the Barbican complex was built during the 1960s and 1970s. The Independent spoke to photographer and resident Anton Rodriguez about what it is like to capture the lives lived out inside the concrete behemoth. London’s Barbican: village life on a City estate. Jane Smith believes she lives in a village – albeit a concrete fortress of a village inside the City of London, with paved terraces and hard-edged water features standing in for the village green and the duck pond.

Sample the FT’s top stories for a week You select the topic, we deliver the news. Not everyone shares her admiration for the Barbican Estate, which has regularly featured in lists of London’s ugliest buildings. Nevertheless this seminal example of brutalist design has quietly established itself as a thriving section of prime central London. Average property prices have risen above £1,000 per sq ft, and the arrival of Crossrail in 2018 should provide a further fillip, giving residents a direct line from nearby Farringdon to the West End and Heathrow airport. “It is a really good place to live,” says Smith, who chairs the Barbican Association. The Barbican Estate was built on a 40-acre former bomb site half a mile northeast of St Paul’s Cathedral.

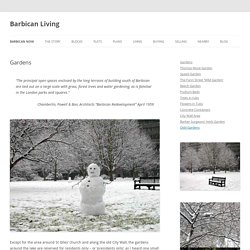

Buying guide. Barbican Living. “The principal open spaces enclosed by the long terraces of building south of Barbican are laid out on a large scale with grass, forest trees and water gardening, as is familiar in the London parks and squares.”Chamberlin, Powell & Bon, Architects “Barbican Redevelopment” April 1959 Except for the area around St Giles’ church and along the old City Wall, the gardens around the lake are reserved for residents only – or ‘presidents only’, as I heard one small child inform her mother – and they are entered via high metal gates to which only residents have keys.

Where lift lobbies open onto the gardens, they also can only be opened with residents’ keys. We have marvellous gardens. You can live for years in the Barbican, just rushing head-down from flat to tube station, and seeing nothing but concrete. If you tell most people who work in the City nearby that there are gardens, and even a lake, hidden between the concrete-ribbed towers, they often just snort with disbelief.