Staking positions amongst the varieties of scientism. By Massimo Pigliucci I have never understood why there is so much confusion about the definition of scientism.

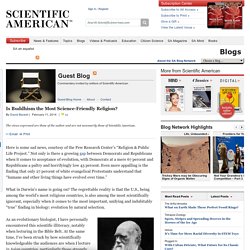

McLean v. Arkansas. McLean v.

Arkansas Board of Education, 529 F. Supp. 1255, 1258-1264 (ED Ark. 1982), was a 1981 legal case in Arkansas. A lawsuit was filed in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas by various parents, religious groups and organizations, biologists, and others who argued that the Arkansas state law known as the Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and Evolution-Science Act (Act 590), which mandated the teaching of "creation science" in Arkansas public schools, was unconstitutional because it violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Arkansas did not appeal the decision and it was not until the 1987 case of Edwards v. Aguillard, which dealt with a similar law passed by the State of Louisiana, that teaching "creation science" was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, making that determination applicable nationwide.[3] Parties[edit] The other plaintiffs were: Background[edit] Arkansas Act 590[edit] Is Buddhism the Most Science-Friendly Religion? The views expressed are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

Here is some sad news, courtesy of the Pew Research Center’s “Religion & Public Life Project.” Not only is there a growing gap between Democrats and Republicans when it comes to acceptance of evolution, with Democrats at a mere 67 percent and Republicans a paltry and horrifyingly low 43 percent. Even more appalling is the finding that only 27 percent of white evangelical Protestants understand that “humans and other living things have evolved over time.”

What in Darwin’s name is going on? The regrettable reality is that the U.S., being among the world’s most religious countries, is also among the most scientifically ignorant, especially when it comes to the most important, unifying and indubitably “true” finding in biology: evolution by natural selection. Portrait of Charles Darwin by Julia Margaret Cameron via Wikimedia Commons Gandhara Buddha / Credit: World Imaging via Wikimedia Commons. The Science Delusion. Curtis White pulls no punches.

To readers who see in Buddhism little room for spirited debate, White’s unapologetic bluntness may seem unexpected or even jarring. But for White—Distinguished Professor Emeritus of English at Illinois State University, novelist, and author of several works of criticism including the 2003 international bestseller The Middle Mind: Why Americans Don’t Think for Themselves—there is too much at stake in our current intellectual climate to indulge in timid discussion.

White’s latest book, The Science Delusion: Asking the Big Questions in a Culture of Easy Answers, strikes out at a nimble opponent, one frequently sighted yet so elusive it often seems to dodge just out of view: scientism. The Science Delusion takes dual aim: at scientists and critics who proclaim themselves “enemies of religion” and at certain neuroscientists and thought leaders in the popular press whose neuro-enthusiasm, White thinks, is adding spin to the facts. How? Time and Now. How could it be that the Buddha's enlightenment occurred simultaneously with all beings?

Didn't this event happen a long time ago? And if it already happened, where is it now? Doesn't "all beings" include us? In Buddhist literature, there appear many references to a kind of timelessness in things, relationships, and events. Nagarjuna, in a classic example, shows us we can have no coherent conception of time as an entity, that time can only be experienced as a set of interdependent relationships. Nevertheless, we commonly look at the world, and our experience of the world, in a linear fashion—as if things were strung out in a line, from past to present to future. Which of these viewpoints is more in keeping with what science now offers us? Some physicists have recently taken a renewed interest in a peculiar way of conceptualizing time and space that has been around since the 1940s.

Some physicists see this as a way to account for consciousness, as well. Let's take a closer look at this. B. Alan Wallace and Buddhist Dualism. Previously I have discussed, largely in the context of an ongoing debate, the notion of cartesian dualism – the belief that consciousness is due, in part or whole, to a non-physical cause separate from the brain.

(I hold the neuroscientific view that consciousness is brain function.) This form of cartesian dualism seems to be favored by Western dualists, like Michael Egnor from the Discovery Institute. There are other forms of dualism as well. David Chalmers, a philosopher of consciousness, holds what he calls naturalistic dualism – that the brain causes mind but consciousness cannot be reduced to brain function.

There therefore must be some higher-order (but still entirely naturalistic) process going on. Today I want to discuss the dualism of B. Wallace has three primary points I want to address. Here There Be Dragons Although he wraps his views in Buddhist mysticism and jargon, Wallace constructs them very similarly to Christian dualist views.