Mercury and health. Mercury exists in various forms: elemental (or metallic) and inorganic (to which people may be exposed through their occupation); and organic (e.g., methylmercury, to which people may be exposed through their diet).

These forms of mercury differ in their degree of toxicity and in their effects on the nervous, digestive and immune systems, and on lungs, kidneys, skin and eyes. Mercury occurs naturally in the earth's crust. Reducing Mercury Pollution. Mercury pollution is released from mining, coal combustion, power plants, and other industrial sources and is traded globally for use in various products and processes.

It can travel halfway around the world before it enters waterways, tainting fish that may be marketed to consumers across the globe. For these reasons, toxic mercury now endangers people on every continent. Tens of thousands of American newborns are estimated to be at risk of impaired motor skills and learning disabilities because their mothers ate fish laden with mercury. As an active coalition member of the Zero Mercury Working Group, we are working with governments and the United Nations to aggressively implement the Minamata Convention on Mercury, a global treaty that aims to reduce the trade, use, and emissions of toxic mercury worldwide. NRDC has also coauthored an essential manual that helps leaders understand the treaty and the steps their countries can take to begin reducing mercury’s toll. Mercury Pollution From Humans Has Reached Bottom of World's Deepest Trench.

Researchers have detected man-made mercury pollution at the bottom of the Mariana Trench—the deepest oceanic trench on the planet.

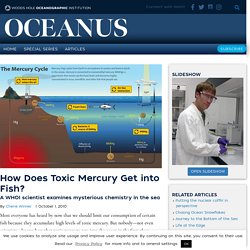

A team of scientists identified methylmercury—a toxic form of mercury that easily accumulates in some animals—in fish and crustaceans living in the trench, which reaches depths of around 36,000 feet. Mercury can be released into the environment from natural sources, such as volcanic eruptions. However, much of the mercury introduced into the oceans comes from human activities, such as the burning of coal and petroleum, or metal-mining and production. Mercury is a potent neurotoxin that can accumulate to harmful levels in some marine species. How Does Toxic Mercury Get into Fish? Most everyone has heard by now that we should limit our consumption of certain fish because they accumulate high levels of toxic mercury.

But nobody—not even scientists—knows how that toxic mercury gets into the ocean in the first place. Here’s the mystery: Most of the mercury that enters the ocean from sources on land or air is just the element mercury, a form that poses little danger because living things can get rid of it quickly. The kind of mercury that accumulates to toxic levels in fish is called monomethylmercury, or simply methylmercury, because it has a methyl group, CH3, attached to the mercury atom. The problem is that we don’t know where methylmercury comes from. Not nearly enough of it enters the ocean to account for the amounts we find in fish.

That’s the puzzle Carl Lamborg, a biogeochemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), is trying to solve. Minamata Bay was one of the worst cases ever of methylmercury poisoning, but sadly, it was not unique. Next steps. New mercury threat to oceans from climate change. A New Source of Methylmercury Entering the Pacific Ocean. Scientists prepare to lower a "rosette" of 12 Niskin bottles on the vessel R/V Thomas G.

Thompson. The device enables the collection of samples in the ocean via remote triggering of each bottle at different depths. Extreme care was taken to ensure that the rosette does not contaminate the samples. Photo courtesy of William Landing, Florida State University. A U.S. Scientists have known for some time that mercury deposited from the atmosphere to freshwater ecosystems can be transformed (methylated) into a highly toxic form of mercury called methylmercury, given the right conditions. Mercury levels: Climate change and overfishing are increasing toxic mercury levels in fish. Mercury levels in the seafood supply are on the rise, and climate change and overfishing are partially to blame, according to a new study.

Scientists said mercury levels in the oceans have fallen since the late 1990s, but levels in popular fish such as tuna, salmon and swordfish are on the rise. According to a new study by Harvard University researchers in the journal Nature, some fish are adapting to overfishing of small herring and sardines by changing their diets to consume species with higher mercury levels.

Based on 30 years of data, methylmercury concentrations in Atlantic cod increased by up to 23% between the 1970s and the 2000s. It links the increase to a diet change necessitated by overfishing. Climate change and overfishing are boosting toxic mercury levels in fish. We live in an era — the Anthropocene — where humans and societies are reshaping and changing ecosystems.

Pollution, human-made climate change and overfishing have all altered marine life and ocean food webs. Increasing ocean temperatures are amplifying the accumulation of neurotoxic contaminants such as organic mercury (methylmercury) in some marine life. This especially affects top predators including marine mammals such as fish-eating killer whales that strongly rely on large fish as seafood for energy.