Working class votes and Conservative losses: solving the UKIP puzzle. Student voters let Tories take key seats. With the dust of May’s unexpected election result well and truly settled, a new report by the Higher Education Policy Institute (Hepi) has assessed what impact student voters had on the outcome.

Here are five things we now know about how students affected the 2015 election. 1. Students could have prevented a Conservative majority government Before the election, Hepi identified six constituencies where a high student population was expected to help overturn a small 2010 majority and see the current Conservative MP lose their seat to Labour (polls show student voters generally prefer Labour to the Tories at a ratio of about two-to-one). Of those six seats, Labour won just one of them. 2. The report suggests that the scale of the defeats in the seats the Liberal Democrats lost meant that students voting against Lib Dems because of their broken promises on tuition fees probably didn’t make any difference – they would have lost their seats anyway. 3. 4. 5. Corbynistas take note! General election 2015: how Britain really voted. The results of Britain's biggest ever post-election survey reveal the nation's changing political character Apart from the obvious—joy for the Tories and SNP, gloom for Labour and the Lib Dems, frustration for Ukip—what really happened on 7th May?

YouGov has done Britain’s biggest ever post-election survey. We have questioned 100,000 people, weighting the data to match both the British electorate and the results of the 2015 general election. The graphics show our main findings. Readers can draw their own conclusions. The biggest divides these days are cultural rather than those of class. Nowadays, women are more likely than men to vote Labour. There is a growing divergence between private and public sector workers. The rise in economic inequality is matched by voting trends.

As in the United States, university graduates are the most likely to vote for progressive parties. Where the votes switched – and why: the key lessons for the parties. Labour The traumatic 2015 results threw the fractures in the contemporary Labour party into sharp relief.

The more a seat looked like London – young, ethnically diverse, highly educated, socially liberal, large public sector – the better Labour did, on the whole. Yet this is the electorate of the future; most of Britain doesn’t look like London yet, and a coalition of Londoners isn’t enough to win elections. Labour fell short with voters outside this “London core”, leaking support in multiple directions. The aspirational voters of suburban England – middle-class seats with falling unemployment and rising incomes – swung behind the Cameron-Osborne “long-term economic plan”, while Ukip surged in seats with large concentrations of poorer, white working-class English nationalists, many of whom sympathised with Labour’s economic message but not the people delivering it.

The choice is hard: any shift to appeal to one group risks alienating others. Conservatives Liberal Democrats. How Britain voted in 2015. For every election since 1979, Ipsos MORI has produced estimates of how the voters voted.

Because the (very successful) exit poll we and GfK carry out for the BBC, ITV and Sky is only designed to predict seat shares, and by virtue of its design gives no demographic information, we hope that these figures provide a useful resource to politicians, commentators, academics and the public themselves to better understand voting behaviour, and the relative performance of the parties. General Election 2015 – Working class votes and Conservative losses: solving ... In this article, Geoffrey Evans and Jonathan Mellon examine the voting history of UKIP supporters, finding that the party is attracting, primarily, disaffected former Labour voters from the Conservatives and elsewhere, and that the working class basis of UKIP has been markedly over-stated.

On the whole, however, it is the Conservatives, not Labour, who have most to fear from UKIP. The idea that many UKIP voters are working class and that UKIP therefore pose a threat to Labour’s support in the forthcoming election has gained considerable currency in recent years. But how do we reconcile evidence of UKIP support among traditional working class voters, and in Labour constituencies, with evidence that UKIP voters report voting Conservative in 2010?

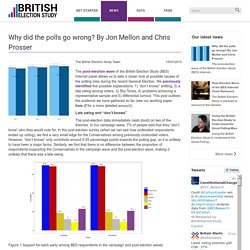

We resolve this contradiction using individual-level panel data stretching back to 2005 to examine the sequencing of vote switching from Labour to UKIP. This is confirmed at the constituency level. Why did the polls go wrong? By Jon Mellon and Chris Prosser - The British Ele... The British Election Study Team The post-election wave of the British Election Study (BES) Internet panel allows us to take a closer look at possible causes of the polling miss during the recent General Election.

We previously identified five possible explanations: 1) “don’t knows” shifting, 2) a late swing among voters, 3) Shy Tories, 4) problems achieving a representative sample and 5) differential turnout. This post outlines the evidence we have gathered so far (see our working paper here for a more detailed account). Late swing and “don’t knows”