1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. An eruption column rose 80,000 feet (24 km; 15 mi) into the atmosphere and deposited ash in 11 U.S. states.[2] At the same time, snow, ice and several entire glaciers on the volcano melted, forming a series of large lahars (volcanic mudslides) that reached as far as the Columbia River, nearly 50 miles (80 km) to the southwest.

Less-severe outbursts continued into the next day, only to be followed by other large, but not as destructive, eruptions later in 1980. Fifty-seven people were killed, including innkeeper Harry R. Truman, photographer Reid Blackburn and geologist David A. Johnston.[3] Hundreds of square miles were reduced to wasteland causing over a billion U.S. dollars in damage ($2.88 billion in 2014 dollars[4]), thousands of game animals were killed, and Mount St.

Helens was left with a crater on its north side. Mount St. Build up to the eruption[edit] St. USGS photo showing a pre-avalanche eruption on April 10. North face slides away[edit] Yellowstone hotspot. Schematic of the hotspot and the Yellowstone Caldera Snake River Plain[edit] The central Snake River plain is similar to the eastern plain, but differs by having thick sections of interbedded lacustrine (lake) and fluvial (stream) sediments, including the Hagerman Fossil Beds.

Nevada-Oregon calderas[edit] The Bruneau-Jarbidge caldera erupted between ten and twelve million years ago, spreading a thick blanket of ash in the Bruneau-Jarbidge event and forming a wide caldera. Animals were suffocated and burned in pyroclastic flows within a hundred miles of the event, and died of slow suffocation and starvation much farther away, notably at Ashfall Fossil Beds, located 1000 miles downwind in northeastern Nebraska, where a foot of ash was deposited. Twin Falls and Picabo volcanic fields[edit] Twin Falls volcanic field and Picabo volcanic field were active about 10 million years ago. Yellowstone Plateau[edit] 640,000BCE: Yellowstone Caldera. Lava Creek Tuff. Extent of the Lava Creek ash bed.

Tuff Cliff showing the Lava Creek Tuff formation. 1.3mya: Henry's Fork Caldera. Mesa Falls Tuff. 2.1mya: Island Park Caldera. Left part of Island Park Caldera, with the circular structure of Henry's Fork Caldera in the center of this image The Island Park Caldera in the states of Idaho and Wyoming, U.S., is one of the world's largest calderas, with approximate dimensions of 80 by 65 km.

Its ashfall is the source of the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff that is found from southern California to the Mississippi River near St. Louis. This super-eruption of approximately 2,500 km3 (600 cu mi) occurred 2.1 Ma (million years ago) and produced 2,500 times as much ash as the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption. Huckleberry Ridge Tuff. Huckleberry Ridge ash bed.

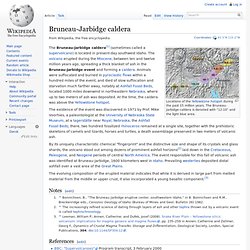

10-12mya: Bruneau-Jarbidge caldera. Locations of the Yellowstone hotspot during the past 15 million years.

The Bruneau-Jarbidge caldera is denoted with "12-10" and the light blue area. The Bruneau-Jarbidge caldera[1] (sometimes called a supervolcano) is located in present-day southwest Idaho. The volcano erupted during the Miocene, between ten and twelve million years ago, spreading a thick blanket of ash in the Bruneau-Jarbidge event and forming a caldera. Animals were suffocated and burned in pyroclastic flows within a hundred miles of the event, and died of slow suffocation and starvation much farther away, notably at Ashfall Fossil Beds, located 1000 miles downwind in northeastern Nebraska, where up to two meters of ash was deposited. Yellowstone Volcano Debate: Both Sides May Be Right.

April 16, 2013 April Flowers for redOrbit.com – Your Universe Online.

Newfound chamber below Old Faithful may drive eruptions - GeoSpace. Scientist have found a chamber beneath Old Faithful that might help fuel its predictable eruptions.

Photo by Barbara Richman, American Geophysical Union. By Sarah Charley A previously unknown underground cavity might help trigger the timely eruptions of the famous Yellowstone geyser Old Faithful, a new study shows. The researchers who uncovered new evidence of a chamber suspect that it stores the pressurized near-boiling water, steam, and other gases that propel Old Faithful’s eruptions. “The first model of geysers made by early explorers one century ago showed a cavity, but no one was able to find the cavity or prove that it existed,” said Jean Vandemeulebrouck of the Université de Savoie in Le Bourget du Lac, France.

There she blows: Scientists discover underground chamber behind the eruptions in Yellowstone's Old Faithful geyser. By Daily Mail Reporter Published: 03:30 GMT, 17 April 2013 | Updated: 12:56 GMT, 17 April 2013 Scientists have discovered a previously unknown chamber beneath Yellowstone's Old Faithful that helps to explain the mechanics behind the geyser's eruptions.

Since it was discovered more than 140 years ago, the geyser has burst forth with amazing regularity and now new research reveals how an underground cavity filled with steam bubbles helps to fuel the massive fountain. 'The first model of geysers made by early explorers one century ago showed a cavity, but no one was able to find the cavity or prove that it existed,' Jean Vandemeulebrouck of the Université de Savoie in Le Bourget du Lac, France, wrote in a paper about the discovery for the Geophysical Research Letters journal.