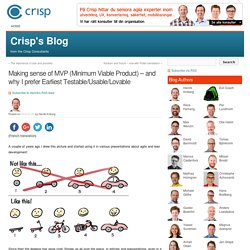

's Blog » Making sense of MVP (Minimum Viable Product) – and why I prefer Earliest Testable/Usable/Lovable. (French translation) A couple of years ago I drew this picture and started using it in various presentations about agile and lean development: Since then the drawing has gone viral!

Shows up all over the place, in articles and presentations, even in a book (Jeff Patton’s “User Story Mapping” – an excellent read by the way). Many tell me the drawing really captures the essence of iterative & incremental development, lean startup, MVP (minimum viable product), and what not. However, some misinterpret it, which is quite natural when you take a picture out of it’s original context. Anyway, with all this buzz, I figured it’s time to explain the thinking behind it. The Art of Saying NO — The App Entrepreneur. The Art of Saying NO A framework to keep crap out of products Great products have one thing in common: A product leader that says “no” to most ideas.

It is that focus — that relentless pursuit of mission — that achieves the impossible: products that touch millions of lives. If you’re in the business of building products, Intercom’s “Product Strategy Means Saying No” is a must read. But in reality, saying “no” is hard. If you’re not Steve Jobs, you know what I mean. Of-course, there’s data. Juha Vainio's Blog - Starting up a game business: Working with Minimum Viable Products. The following blog post, unless otherwise noted, was written by a member of Gamasutra’s community.

The thoughts and opinions expressed are those of the writer and not Gamasutra or its parent company. Originally published in Epic Owl's blog: This time I would like to write about the concept of Minimum Viable Product and what it means in the context of Epic Owl’s game production. This topic was inspired by my recent debate in Twitter with Game Design Guru Warren Spector who read Risto’s latest design article (Part 6) and commented that he thinks releasing MVPs show contempt for the audience.

Needless to say, I had to comment on that and explain why I think MVP is an important tool for any game developer and has nothing to do with contempt. Planning fallacy: why people suck at planning. Jutta Eckstein - Complex Projects aren't planable but controllable, Science has finally approved it: Forecasting complex projects is a deception. Moreover,... The Disciplined Pursuit of Less - Greg McKeown. By Greg McKeown | 10:00 AM August 8, 2012 Why don’t successful people and organizations automatically become very successful?

One important explanation is due to what I call “the clarity paradox,” which can be summed up in four predictable phases: Phase 1: When we really have clarity of purpose, it leads to success. Phase 2: When we have success, it leads to more options and opportunities. Phase 3: When we have increased options and opportunities, it leads to diffused efforts. Curiously, and overstating the point in order to make it, success is a catalyst for failure. We can see this in companies that were once darlings of Wall Street, but later collapsed. Here’s a more personal example: For years, Enric Sala was a professor at the prestigious Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California. What can we do to avoid the clarity paradox and continue our upward momentum? First, use more extreme criteria. Second, ask “What is essential?”

Conducting a life audit. AgileQuotes.com.

Scope creep. If budget, resources, and schedule are increased along with the scope, the change is usually considered an acceptable addition to the project, and the term “scope creep” is not used.

Race to Running Software. Running software is the best way to build momentum, rally your team, and flush out ideas that don't work.

Race to Running Software. Hold the Mayo. Most software surveys and research questions are centered around what people want in a product.

"What feature do you think is missing? " "If you could add just one thing, what would it be? " "What would make this product more useful for you? " What about the other side of the coin? Forget Feature Requests. Customers want everything under the sun.

They'll avalanche you with feature requests. Just check out our product forums; The feature request category always trumps the others by a wide margin. We'll hear about "this little extra feature" or "this can't be hard" or "wouldn't it be easy to add this" or "it should take just a few seconds to put it in" or "if you added this I'd pay twice as much" and so on.

Of course we don't fault people for making requests. We encourage it and we want to hear what they have to say. Yup, read them, throw them away, and forget them. It's a Problem When It's a Problem. Don't waste time on problems you don't have yet Do you really need to worry about scaling to 100,000 users today if it will take you two years to get there?

Fix Time and Budget, Flex Scope. Here's an easy way to launch on time and on budget: keep them fixed.

Never throw more time or money at a problem, just scale back the scope. PurposeOfEstimation. Metrics · project planning · estimation tags: My first encounter with agile software development was working with Kent Beck at the dawn of Extreme Programming. One of the things that impressed me about that project was the way we went about planning. The Big Lie of Strategic Planning. All executives know that strategy is important.

But almost all also find it scary, because it forces them to confront a future they can only guess at. Worse, actually choosing a strategy entails making decisions that explicitly cut off possibilities and options. An executive may well fear that getting those decisions wrong will wreck his or her career. The natural reaction is to make the challenge less daunting by turning it into a problem that can be solved with tried and tested tools. That nearly always means spending weeks or even months preparing a comprehensive plan for how the company will invest in existing and new assets and capabilities in order to achieve a target—an increased share of the market, say, or a share in some new one.

This is a truly terrible way to make strategy. In this worldview, managers accept that good strategy is not the product of hours of careful research and modeling that lead to an inevitable and almost perfect conclusion.