Edward Koiki (Eddie) Mabo. Edward ‘Koiki’ Mabo (1936–1992), Torres Strait Islander community leader and land rights campaigner, was born on 29 June 1936 at Las, on Mer, in the Murray group of islands, Queensland, the fourth surviving child of Murray Islands-born parents ‘Robert’ Zesou Sambo, seaman, and his wife ‘Annie’ Poipe, née Mabo.

Koiki’s mother died five days after his birth and he was adopted by his maternal uncle and aunt, Benny and Maiga Mabo, in accordance with Islander custom. As a child he participated in fishing and farming activities on Mer, absorbing Meriam culture. His first language was Meriam, but he also spoke Torres Strait Islander creole. He learnt English at the state school with special assistance from one of his teachers, Bob Miles, who recognised his ability and stressed the importance of English for his future involvement in mainland culture. His first two jobs were as a teachers’ aide and as an interpreter for a medical research team in the Torres Strait. Indigenous res006 0712. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Land rights for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples refers to the ongoing struggle to gain legal and moral recognition of ownership of lands and waters they called home prior to colonisation of Australia in 1788.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ laws and customs and ways of knowing and being in the world are intimately connected to the land and waters. Connection to land is therefore essential to the continued cultural survival of Indigenous Australians as well as their economic and social development. Yirrkala bark petitions The modern land rights movement dates back to 1963 when the Yolgnu people from the settlement Yirrkala in north-east Arnhem Land (Northern Territory) presented the Australian Parliament with a bark petition, commonly known as the Yirrkala bark petitions, protesting to have their land and their rights returned.

Wave Hill walk off During this era the Wave Hill walk off also took place. Indigenous rights. Indigneous Victorian communities have a rich history, passed on to us through art, activism and oral history Find out about Native Title. Timeline: Aboriginal Tent Embassy. The history of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy. Updated 27 Jan 2012, 2:50amFri 27 Jan 2012, 2:50am.

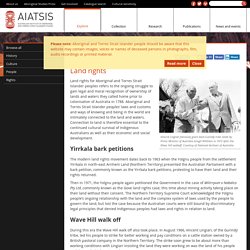

Collaborating for Indigenous Rights 1957-1973. We want land rights, not handouts Alan Sharpley with placard, Bob Perry in a Ningla-a-Na T-shirt and John Newfong with hands on hips at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra.

The Pitjantjatjara expression Ningla-a-Na is translated as 'we are hungry for our land'. Source: Ken Middleton collection, National Library of Australia Late on Australia Day 1972, four young Aboriginal men erected a beach umbrella on the lawns outside Parliament House in Canberra and put up a sign which read 'Aboriginal Embassy'. The Land. Indigenous people have occupied Australia for at least 60 000 years and have evolved with the land.

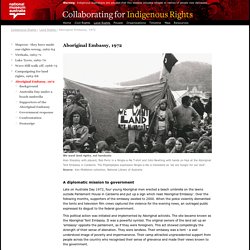

NSW Bark canoe E045964 Photographer: Stuart Humphreys © Australian Museum Changing it and changing with it. The land was not just soil or rocks or minerals, but a whole environment that sustains, and is sustained, by people and culture. "I feel with my body. Feeling all these trees, all this country. Collaborating for Indigenous Rights 1957-1973. Land rights march in Melbourne, 1968 Students, Aboriginal activists and others respond to Cabinet's refusal to make tribal lands available to the Gurindji of Wave Hill.Source: Courtesy Melbourne Sun, 13 July 1968 Land rights for Aborigines caught the public imagination, especially within the counter-culture, among students and among city-based Aboriginal activists beginning to flex their political muscles.

More unusually, religious leaders critical of church hierarchies which had turned a blind eye to the injustices experienced by Aboriginal Australians, public intellectuals and politicians spoke out for land for Aboriginal people. A National Missionary Council pamphlet published in 1963 states unequivocally: The Wave Hill walk-off: more than a wage dispute - History (6,10) 00:00:10:13REPORTER:Blackfella's country - until recently, few people realised that there might be such a thing.

The idea that the Aborigine might own some of the land he discovered 100,000 years ago is one of the rude awakenings for Australians in the 1960s.00:00:24:24MAN:(Plays didgeridoo)00:00:30:23REPORTER:And these are the people who brought about the awakening, the Gurindjis, the remnants of a once-magnificent tribe now dressed like Hollywood extras and set against a background of squalor. The Gurindjis are almost without exception stockmen. They first pricked the national conscience in 1966 when they went on strike at Wave Hill Station, 500 miles south of Darwin. Fight for rights. Collaborating for Indigenous Rights 1957-1973. Vincent Lingiari and Mick Rangiari at the sign they asked Frank Hardy to make, 1966 This was probably the first time Gurindji people had seen their name for themselves written down.Source: National Archives, of Australia, Darwin In August 1966, Aboriginal pastoral workers walked off the job on the vast Vesteys' cattle station at Wave Hill in the Northern Territory.

At first they expressed their unhappiness with their poor working conditions and disrespectful treatment. Conversations between stockmen who had worked for Vesteys and Dexter Daniels, the North Australian Workers' Union Aboriginal organiser, led to the initial walk off. The next year the group moved to Wattie Creek, a place of significance to the Gurindji people. They asked Frank Hardy to 'make a sign' which included the word 'Gurindji', their own name for themselves. Although these stockmen and their families could not read, they understood the power of the white man's signs. I bin thinkin' this bin Gurindji country. The Trust. Unlike other stations, the practising of culture at Lake Tyers received some official support.

The first Mission manager, John Bulmer, encouraged the residents to continue their hunting practices to subsidise their rations. Bulmer even requested that an exclusive area of waters be established for the Mission residents when changes in the law threatened fishing activities. The request was denied and as a result many residents were forced to find an alternative livelihood. By the late 1870s the Gippsland Lakes were a popular tourist destination and a visit to the Lake Tyers Mission became a must for holidaymakers. In 1878 the Board encouraged Bulmer to maintain a ‘visitor’s book’ to record the names of tourists visiting the Mission.

Fighting for Lake Tyers - No 85 May 2010 - La Trobe Journal. Morale at Lake Tyers was low.

There were twice-weekly rations. Educational opportunities were limited to basic primary school education provided on the reserve and, as a consequence, residents were totally out of touch with the processes involved in influencing Government decision-making. How then was a campaign to be waged? Mabo/Lake Tyers Reserve, 1861-1970. Lake Tyers Reserve. Collaborating for Indigenous Rights 1957-1973. Charlie Carter receives title deed to Lake Tyers Charlie Carter receives the title deed to Lake Tyers on behalf of residents. Rohan Delacombe, Governor of Victoria, is to his right. Pastor Doug Nicholls, far left, looks on. Bark petitions: Indigenous art and reform for the rights of Indigenous Australians.

Warning. Australian Stories may contain the names and images of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people now deceased. Australian Stories also contain links to sites that may use images of Aboriginal and Islander people now deceased. In August 1963 a petition presented as a pair of bark paintings was sent to the Australian Parliament, signed by 131 clan leaders of the Yolngu region (Gove Peninsula) of the Northern territory. There had been many earlier petitions from Aboriginal people to Australian parliaments. Collaborating for Indigenous Rights 1957-1973. Justice Woodward, Frank Purcell, Roy Marika and other residents at land rights hearing This photo was taken at Yirrkala. It is not dated but would most likely have been taken in 1971. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Introduction. Collaborating for Indigenous Rights 1957-1973.