Shroud of Turin. The Shroud of Turin: modern photo of the face, positive left, negative right.

Negative has been contrast enhanced. The origins of the shroud and its image are the subject of intense debate among theologians, historians and researchers. Scientific and popular publications have presented diverse arguments for both authenticity and possible methods of forgery. A variety of scientific theories regarding the shroud have since been proposed, based on disciplines ranging from chemistry to biology and medical forensics to optical image analysis. The Catholic Church has neither formally endorsed nor rejected the shroud, but in 1958 Pope Pius XII approved of the image in association with the devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus.[2] More recently, Pope Francis and his predecessor Pope Benedict XVI have both described the Shroud of Turin as “an icon”. Description[edit] Markings on the cloth have been interpreted as follows:[12] History[edit] Religious perspective[edit] Criticism by John Calvin[edit]

Veil of Veronica. The Veil of Veronica, or Sudarium (Latin for sweat-cloth), often called simply "The Veronica" and known in Italian as the Volto Santo or Holy Face (but not to be confused with the carved crucifix Volto Santo of Lucca) is a Catholic relic of a piece of cloth, which, according to legend, bears the likeness of the face of Jesus not made by human hand (i.e. an Acheiropoieton).

Various existing images have been claimed to be the "original" relic, or early copies of it, but the evidently legendary nature of the story means that there are many fewer people, even among traditional Catholics, who treat claims of actual authenticity very seriously compared to the comparable relic of the Turin Shroud. The final form of the Western legend recounts that Saint Veronica from Jerusalem encountered Jesus along the Via Dolorosa on the way to Calvary. When she paused to wipe the blood and sweat (Latin sudor) off his face with her veil, his image was imprinted on the cloth.

The story[edit] St. Type I Type II. Image of Edessa. According to the legend, King Abgar received the Image of Edessa, a likeness of Jesus.

According to Christian tradition, the Image of Edessa was a holy relic consisting of a square or rectangle of cloth upon which a miraculous image of the face of Jesus was imprinted — the first icon ("image"). In Eastern Orthodoxy, and often in English, the image is known as the Mandylion. According to the legend, King Abgar of Edessa wrote to Jesus, asking him to come cure him of an illness.

Abgar received a reply letter from Jesus, declining the invitation, but promising a future visit by one of his disciples. This legend was first recorded in the early 4th century by Eusebius of Caesarea,[1] who said that he had transcribed and translated the actual letter in the Syriac chancery documents of the king of Edessa, but who makes no mention of an image.[2] Instead, the apostle "Thaddaeus" is said to have come to Edessa, bearing the words of Jesus, by the virtues of which the king was miraculously healed.

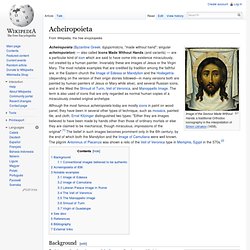

Acheiropoieta. Image of the Saviour Made Without Hands: a traditional Orthodox iconography in the interpretation of Simon Ushakov (1658).

Acheiropoieta (Byzantine Greek: ἀχειροποίητα, "made without hand"; singular acheiropoieton) — also called Icons Made Without Hands (and variants) — are a particular kind of icon which are said to have come into existence miraculously, not created by a human painter. Invariably these are images of Jesus or the Virgin Mary.

The most notable examples that are credited by tradition among the faithful are, in the Eastern church the Image of Edessa or Mandylion and the Hodegetria (depending on the version of their origin stories followed—in many versions both are painted by human painters of Jesus or Mary while alive), and several Russian icons, and in the West the Shroud of Turin, Veil of Veronica, and Manoppello Image. The term is also used of icons that are only regarded as normal human copies of a miraculously created original archetype. Background[edit]