Semantic satiation History and research[edit] The phrase "semantic satiation" was coined by Leon Jakobovits James in his doctoral dissertation at McGill University, Montreal, Canada awarded in 1962.[1] Prior to that, the expression "verbal satiation" had been used along with terms that express the idea of mental fatigue. The dissertation listed many of the names others had used for the phenomenon: "Many other names have been used for what appears to be essentially the same process: inhibition (Herbert, 1824, in Boring, 1950), refractory phase and mental fatigue (Dodge, 1917; 1926a), lapse of meaning (Bassett and Warne, 1919), work decrement (Robinson and Bills, 1926), cortical inhibition (Pavlov, 192?) The explanation for the phenomenon was that verbal repetition repeatedly aroused a specific neural pattern in the cortex which corresponds to the meaning of the word. Applications[edit] In popular culture[edit] See also[edit] References[edit] Further reading[edit] Dodge, R.

Milgram experiment The experimenter (E) orders the teacher (T), the subject of the experiment, to give what the latter believes are painful electric shocks to a learner (L), who is actually an actor and confederate. The subject believes that for each wrong answer, the learner was receiving actual electric shocks, though in reality there were no such punishments. Being separated from the subject, the confederate set up a tape recorder integrated with the electro-shock generator, which played pre-recorded sounds for each shock level.[1] The experiments began in July 1961, three months after the start of the trial of German Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. Milgram devised his psychological study to answer the popular question at that particular time: "Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?" The experiment[edit] Milgram Experiment advertisement Results[edit] Criticism[edit] Ethics[edit] Replications[edit]

Stanford prison experiment The Stanford prison experiment (SPE) was a study of the psychological effects of becoming a prisoner or prison guard. The experiment was conducted at Stanford University from August 14–20, 1971, by a team of researchers led by psychology professor Philip Zimbardo.[1] It was funded by the US Office of Naval Research[2] and was of interest to both the US Navy and Marine Corps as an investigation into the causes of conflict between military guards and prisoners. Goals and methods[edit] Zimbardo and his team aimed to test the hypothesis that the inherent personality traits of prisoners and guards are the chief cause of abusive behavior in prison. The experiment was conducted in the basement of Jordan Hall (Stanford's psychology building). The researchers held an orientation session for guards the day before the experiment, during which they instructed them not to physically harm the prisoners. The prisoners were "arrested" at their homes and "charged" with armed robbery. Results[edit] [edit]

Sense of agency The "sense of agency" (SA) refers to the subjective awareness that one is initiating, executing, and controlling one's own volitional actions in the world.[1] It is the pre-reflective awareness or implicit sense that it is I who is executing bodily movement(s) or thinking thoughts. In normal, non-pathological experience, the SA is tightly integrated with one's "sense of ownership" (SO), which is the pre-reflective awareness or implicit sense that one is the owner of an action, movement or thought. If someone else were to move your arm (while you remained passive) you would certainly have sensed that it were your arm that moved and thus a sense of ownership (SO) for that movement. Normally SA and SO are tightly integrated, such that while typing one has an enduring, embodied, and tacit sense that "my own fingers are doing the moving" (SO) and that "the typing movements are controlled (or volitionally directed) by me" (SA). Definition[edit] Neuroscience of the sense of agency[edit]

Proprioception The cerebellum is largely responsible for coordinating the unconscious aspects of proprioception. Proprioception (/ˌproʊpri.ɵˈsɛpʃən/ PRO-pree-o-SEP-shən), from Latin proprius, meaning "one's own", "individual" and perception, is the sense of the relative position of neighbouring parts of the body and strength of effort being employed in movement.[1] It is provided by proprioceptors in skeletal striated muscles and in joints. It is distinguished from exteroception, by which one perceives the outside world, and interoception, by which one perceives pain, hunger, etc., and the movement of internal organs. The brain integrates information from proprioception and from the vestibular system into its overall sense of body position, movement, and acceleration. The word kinesthesia or kinæsthesia (kinesthetic sense) has been used inconsistently to refer either to proprioception alone or to the brain's integration of proprioceptive and vestibular inputs. History of study[edit] Components[edit]

Operant conditioning Diagram of operant conditioning Operant conditioning separates itself from classical conditioning because it is highly complex, integrating positive and negative conditioning into its practices; whereas, classical conditioning focuses only on either positive or negative conditioning but not both together. Another dubbing of operant conditioning is instrumental learning. Instrumental conditioning was first discovered and published by Jerzy Konorski and was also referred to as Type II reflexes. Operant behavior operates on the environment and is maintained by its antecedents and consequences, while classical conditioning is maintained by conditioning of reflexive (reflex) behaviors, which are elicited by antecedent conditions. Historical notes[edit] Thorndike's law of effect[edit] Main article: Law of effect Operant conditioning, sometimes called instrumental learning, was first extensively studied by Edward L. Skinner[edit] Main article: B. B.F. Tools and procedures[edit] See also[edit] 1.

Macdonald triad The Macdonald triad (also known as the triad of sociopathy or the homicidal triad) is a set of three behavioral characteristics that has been suggested, if all three or any combination of two, are present together, to be predictive of or associated with, later violent tendencies, particularly with relation to serial offenses. The triad was first proposed by psychiatrist J.M. Macdonald in "The Threat to Kill", a 1963 paper in the American Journal of Psychiatry.[1] Small-scale studies conducted by psychiatrists Daniel Hellman and Nathan Blackman, and then FBI agents John E. Douglas and Robert K. The triad links cruelty to animals, obsession with fire setting, and persistent bedwetting past a certain age, to violent behaviors, particularly homicidal behavior and sexually predatory behavior.[5] Some other studies claim to have not found statistically significant links between the triad and violent offenders. Firesetting[edit] Cruelty to animals[edit] Enuresis[edit] See also[edit]

Madonna–whore complex Inability to maintain sexual arousal within a committed, loving relationship Freud argued that the Madonna–whore complex was caused by a split between the affectionate and the sexual currents in male desire.[5] Oedipal and castration anxiety fears prohibit the affection felt for past incestuous objects from being attached to women who are sensually desired: "The whole sphere of love in such persons remains divided in the two directions personified in art as sacred and profane (or animal) love".[5] In order to minimize anxiety, the man categorizes women into two groups: women he can admire and women he finds sexually attractive. Whereas the man loves women in the former category, he despises and devalues the latter group.[6] Psychoanalyst Richard Tuch suggests that Freud offered at least one alternative explanation for the Madonna–whore complex: Feminist interpretations [edit] Cultural representations Bareket, O., Kahalon, R., Shnabel, N., & Glick, P. (2018).

Self-awareness Self-awareness is the capacity for introspection and the ability to recognize oneself as an individual separate from the environment and other individuals.[1] It is not to be confused with consciousness. While consciousness is being aware of one’s environment and body and lifestyle, self-awareness is the recognition of that consciousness.[2] Neurobiological basis[edit] There are questions regarding what part of the brain allows us to be self-aware and how we are biologically programmed to be self- aware. V.S. Ramachandran has speculated that mirror neurons may provide the neurological basis of human self-awareness.[3] In an essay written for the Edge Foundation in 2009 Ramachandran gave the following explanation of his theory: "... Animals[edit] Studies have been done mainly on primates to test if self-awareness is present. The ‘Red Spot Technique’ created and experimented by Gordon Gallup[6] studies self-awareness in animals (primates). Psychology[edit] Developmental stages[edit] [edit]

False consensus effect Attributional type of cognitive bias In psychology, the false consensus effect, also known as consensus bias, is a pervasive cognitive bias that causes people to “see their own behavioral choices and judgments as relatively common and appropriate to existing circumstances”. In other words, they assume that their personal qualities, characteristics, beliefs, and actions are relatively widespread through the general population. This false consensus is significant because it increases self-esteem (overconfidence effect). The false consensus effect has been widely observed and supported by empirical evidence. Major theoretical approaches[edit] The false-consensus effect can be traced back to two parallel theories of social perception, "the study of how we form impressions of and make inferences about other people". The second influential theory is projection, the idea that people project their own attitudes and beliefs onto others.[12] This idea of projection is not a new concept. Notes[edit]

Frequency illusion Cognitive bias Frequency illusion, also known as the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon or frequency bias, is a cognitive bias referring to the tendency to notice something more often after noticing it for the first time, leading to the belief that it has an increased frequency of occurrence.[1][2][3] The illusion is a result of increased awareness of a phrase, idea, or object – for example, hearing a song more often or seeing red cars everywhere.[4][5] The Baader-Meinhof group, which the phenomenon is named after, was a far-left German terrorist organization active in the 1970s. The name “Baader-Meinhof phenomenon” was coined in 1994 by an online message board user, who, after mentioning the name of the German terrorist group Baader-Meinhof once, kept noticing it, and posted on the forum about their experience. Causes[edit] Several possible causes behind frequency illusion have been put forth. Selective attention[edit] Confirmation bias[edit] Recency illusion[edit] Split-category effect[edit]

Crab mentality Metaphor about spiteful attitude Crab mentality, also known as crab theory,[1][2] crabs in a bucket[a] mentality, or the crab-bucket effect, is a mentality of which people will try to prevent others from gaining a favourable position in something, even if it has no effect on those trying to stop them. It is usually summarized with the phrase "If I can't have it, neither can you".[3] The metaphor is derived from anecdotal claims about the behavior of crabs contained in an open bucket: if a crab starts to climb out,[4] it will be pulled back in by the others, ensuring the group's collective demise.[5][6][7] Self-evaluation maintenance theory [edit] Tesser's self-evaluation maintenance theory (SEM)[12] suggests that individuals engage in self-evaluation not only through introspection but also through comparison to others, especially those within their close social circles. Relative deprivation theory ^ Instead of bucket - barrel, basket, or pot are all also commonly used.

Kirkbride Plan Mental asylum design created by Thomas Kirkbride The Kirkbride Plan was a system of mental asylum design advocated by American psychiatrist Thomas Story Kirkbride (1809–1883) in the mid-19th century. The asylums built in the Kirkbride design, often referred to as Kirkbride Buildings (or simply Kirkbrides), were constructed during the mid-to-late-19th century in the United States. The structural features of the hospitals as designated by Kirkbride were contingent on his theories regarding the healing of the mentally ill, in which environment and exposure to natural light and air circulation were crucial. The hospitals built according to the Kirkbride Plan would adopt various architectural styles, but had in common the "bat wing" style floor plan, housing numerous wings that sprawl outward from the center.[2] The first hospital designed under the Kirkbride Plan was the Trenton State Hospital in Trenton, New Jersey, constructed in 1848. History[edit] Basis and philosophy[edit] Future[edit]

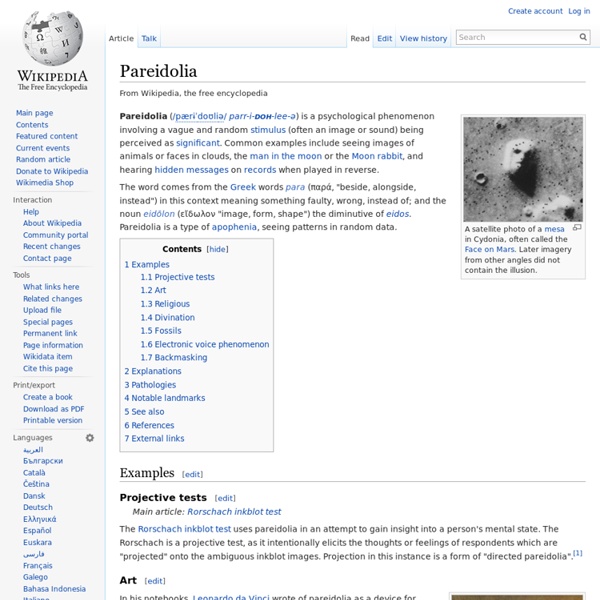

Apophenia Apophenia /æpɵˈfiːniə/ is the experience of perceiving patterns or connections in random or meaningless data. The term is attributed to Klaus Conrad[1] by Peter Brugger,[2] who defined it as the "unmotivated seeing of connections" accompanied by a "specific experience of an abnormal meaningfulness", but it has come to represent the human tendency to seek patterns in random information in general, such as with gambling and paranormal phenomena.[3] Meanings and forms[edit] In 2008, Michael Shermer coined the word "patternicity", defining it as "the tendency to find meaningful patterns in meaningless noise".[6][7] In The Believing Brain (2011), Shermer says that we have "the tendency to infuse patterns with meaning, intention, and agency", which Shermer calls "agenticity".[8] Statistics[edit] Pareidolia[edit] Pareidolia is a type of apophenia involving the perception of images or sounds in random stimuli, for example, hearing a ringing phone while taking a shower. Gambling[edit] Examples[edit]