Armenian mythology Armenian mythology was strongly influenced by Zoroastrianism, with deities such as Aramazd, Mihr or Anahit, as well as Assyrian traditions, such as Barsamin, but there are fragmentary traces of native traditions, such as Hayk or Vahagn and Astghik. According to De Morgan there are signs which indicate that the Armenians were initially nature worshipers and that this faith in time was transformed to the worship of national gods, of which many were the equivalents of the gods in the Roman, Persian and Greek cultures. Georg Brandes described the Armenian gods in his book: “When Armenia accepted Christianity, it was not only the temples which were destroyed, but also the songs and poems about the old gods and heroes that the people sang. We have only rare segments of these songs and poems, segments which bear witness of a great spiritual wealth and the power of creation of this people and these alone are sufficient reason enough for recreating the temples of the old Armenian gods. Totemism

Jinn Imam Ali Conquers Jinn Unknown artist Ahsan-ol-Kobar 1568 Golestan Palace. Together, the jinn, humans and angels make up the three sapient creations of God. Like human beings, the jinn can be good, evil, or neutrally benevolent and hence have free will like humans and unlike angels.[3] Etymology and definitions[edit] Jinn is a noun of the collective number in Arabic literally meaning "hidden from sight", and it derives from the Arabic root j-n-n (pronounced: jann/ junn جَنّ / جُنّ) meaning "to hide" or "be hidden". Other words derived from this root are majnūn 'mad' (literally, 'one whose intellect is hidden'), junūn 'madness', and janīn 'embryo, fetus' ('hidden inside the womb').[4] In Arabic, the word jinn is in the collective number, translated in English as plural (e.g., "several genies"); jinnī is in the singulative number, used to refer to one individual, which is translated by the singular in English (e.g., "one genie"). In the pre-Islamic era[edit] In Islam[edit] Qarīn[edit]

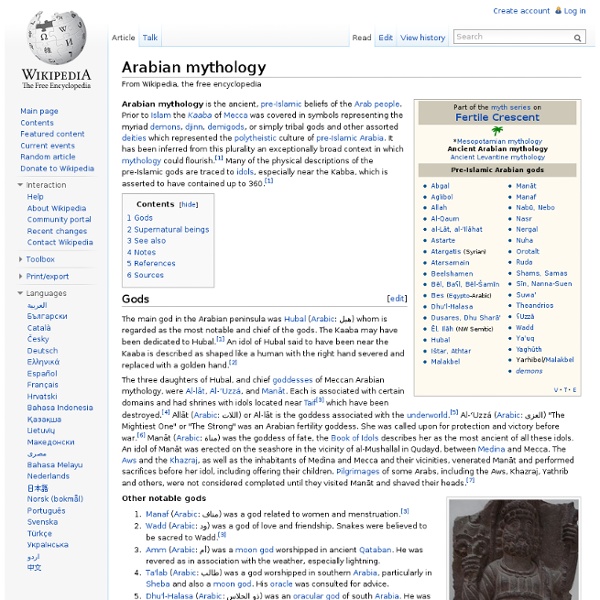

Islamic mythology Islamic mythology is the body of traditional narratives associated with Islam from a mythographical perspective. Many Muslims regard these narratives as historical and sacred and believe they contain profound truths. These traditional narratives include, but are not limited to, the stories contained in the Qur'an. Followers of Islam (Muslims) believe that Islam, in its current form, was established by God, through the prophet Muhammed, who lived in the 6th and 7th centuries CE.[1] Muslims believe that all true prophets (including Musa and Isa) preached Islamic principles that were applicable in their time but when the times changed and people needed new guidance for new situations, God appointed a new prophet with a new code of life that could guide them. Central Islam stories[edit] Life of Muhammad[edit] The Kaaba[edit] According to Islamic tradition, God instructed Adam to construct a building to be the earthly counterpart of the House of Heaven. Biblical stories in the Qur'an[edit]

Persian mythology Persian mythology are traditional tales and stories of ancient origin, all involving extraordinary or supernatural beings. Drawn from the legendary past of Iran, they reflect the attitudes of the society to which they first belonged - attitudes towards the confrontation of good and evil, the actions of the gods, yazats (lesser gods), and the exploits of heroes and fabulous creatures. Myths play a crucial part in Iranian culture and our understanding of them is increased when we consider them within the context of Iranian history. For this purpose we must ignore modern political boundaries and look at historical developments in the Greater Iran, a vast area covering parts of Central Asia well beyond the frontiers of present-day Iran. The geography of this region, with its high mountain ranges, plays a significant role in many of the mythological stories. Key texts[edit] The central collection of Persian mythology is the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, written over a thousand years ago.

Ishtar Ishtar (English pronunciation /ˈɪʃtɑːr/; Transliteration: DIŠTAR; Akkadian: 𒀭𒈹 ; Sumerian 𒀭𒌋𒁯) is the East Semitic Akkadian, Assyrian and Babylonian goddess of fertility, love, war, and sex.[1] She is the counterpart to the Sumerian Inanna, and is the cognate for the Northwest Semitic Aramean goddess Astarte. Characteristics[edit] Ishtar was the goddess of love, war, fertility, and sexuality. Ishtar was the daughter of Ninurta.[2] She was particularly worshipped in northern Mesopotamia, at the Assyrian cities of Nineveh, Ashur and Arbela (Erbil).[2] Besides the lions on her gate, her symbol is an eight-pointed star.[3] One type of depiction of Ishtar/Inanna Ishtar had many lovers; however, as Guirand notes, Descent into the underworld[edit] One of the most famous myths[5] about Ishtar describes her descent to the underworld. If thou openest not the gate to let me enter, I will break the door, I will wrench the lock, I will smash the door-posts, I will force the doors. In other media[edit]

Ossetian mythology The mythology of the Ossetian people of the Caucasus region contains several gods and supernatural beings. The religion itself is believed to be of Sarmatian origin, but contains many later elements from Christianity, and the Ossetian gods are often identified with Christian saints. The gods play a role in the famous stories about a race of semi-divine heroes called the Narts. The uac- prefix in Uastyrdzhi and Uacilla has no synchronic meaning in Ossetic, and is usually understood to mean "saint" (also applied to Tutyr, Uac Tutyr, perhaps Saint Theodore, and to Saint Nicholas, Uac Nikkola). Kurys (Digor Burku) is a dream land, a meadow belonging to the dead, which can be visited by some people in their sleep. See also[edit] References[edit] Jump up ^ Arys-Djanaïeva p.163Jump up ^ Arys-Djanaïeva p.163Jump up ^ Lurker, Manfred (1987), The Routledge Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses, Devils and Demons, Routledge, p. 30, ISBN 0-415-34018-7 Jump up ^ Arys-Djanaïeva p.165 Sources[edit]

Hittite mythology Seated deity, late Hittite Empire (13th century BC) The understanding of Hittite mythology depends on readings of surviving stone carvings, deciphering of the iconology represented in seal stones, interpreting ground plans of temples: additionally, there are a few images of deities, for the Hittites often worshipped their gods through Huwasi stones, which represented deities and were treated as sacred objects. Gods were often depicted standing on the backs of their respective beasts, or may have been identifiable in their animal form.[3] Overview[edit] Priests and cult sites[edit] The liminal figure mediating between the intimately connected worlds of gods and mankind was the king and priest; in a ritual dating from the Hittite Old Kingdom period: The gods, the Sun-God and the Storm-God, have entrusted to me, the king, the land and my household, so that I, the king, should protect my land and my household, for myself.[5] Deities and their myths[edit] List of Hittite deities[15][edit]

Modern Times (1936) Kurdish mythology Kurdish mythology is the collective term for the beliefs and practices of the culturally, ethnically or linguistically related group of ancient peoples who inhabited the Kurdistan mountains of northwestern Zagros near northern Mesopotamia. In Kurdish mythology, Kurds are descended of people who fled to the mountains to save their lives from the oppression of a king named Zahhak. It is believed that the people, like Kaveh the Blacksmith who fled and hid in the mountains over the course of history created a Kurdish ethnicity. (Bulloch and Morris. p50) Mountains, to this day, are still important geographical and symbolic figures in Kurdish life. References[edit] See also[edit] Iranian mythology

White Palace 09 Baskervilles : The Light upon the Moor - Storynory - Free Audio Stories for kids Doctor Watson continues his report. The Butler Barrymore is behaving extremely suspiciously. Read by Richard Scott. Chapter 9. The Light upon the Moor [Second Report of Dr. Baskerville Hall, Oct. 15th. Before breakfast on the morning following my adventure I went down the corridor and examined the room in which Barrymore had been in the night before. But whatever the true explanation of Barrymore’s movements might be, I felt that the responsibility of keeping them to myself until I could explain them was more than I could bear. “I knew that Barrymore walked about nights, and I had a mind to speak to him about it,” said he. “Perhaps then he pays a visit every night to that particular window,” I suggested. “Perhaps he does. “I believe that he would do exactly what you now suggest,” said I. “Then we shall do it together.” “But surely he would hear us.” “The man is rather deaf, and in any case we must take our chance of that. “What, are you coming, Watson?” “Yes, I am.” “Halloa, Watson!