Academic Dishonesty and Plagiarism Academic DishonestyAcademic dishonesty includes cheating, plagiarism, and any attempt to obtain credit for academic work through fraudulent, deceptive, or dishonest means. Below is a list of some forms academic dishonesty may take. Using or attempting to use unauthorized materials, information, or study aids in any academic exerciseSubmitting work previously submitted in another course without the consent of the instructorSitting for an examination by surrogate or acting as a surrogateRepresenting the words, ideas, or work of another as one’s own in any academic exerciseConducting any act that defrauds the academic process PlagiarismPlagiarism is the presentation of someone else’s ideas or work as one’s own. As such, plagiarism constitutes fraud or theft. If an instructor determines there is sufficient evidence of academic dishonesty on the part of a student, the instructor may exercise one or more of the following options:

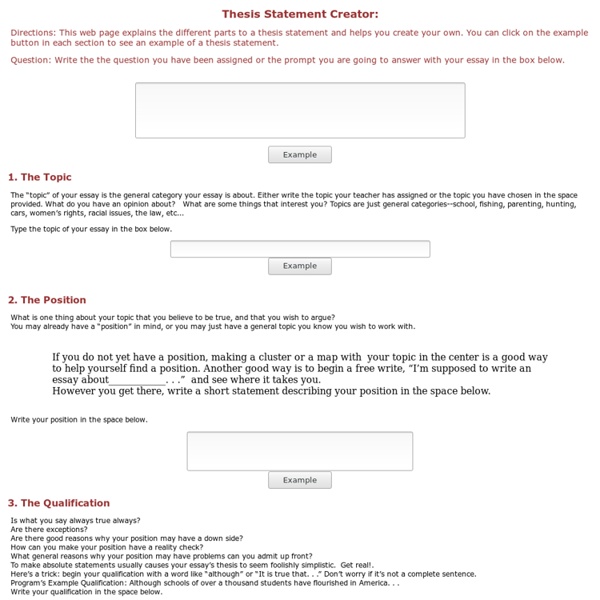

Thesis Statements What is a Thesis Statement? Almost all of us—even if we don’t do it consciously—look early in an essay for a one- or two-sentence condensation of the argument or analysis that is to follow. We refer to that condensation as a thesis statement. Why Should Your Essay Contain a Thesis Statement? to test your ideas by distilling them into a sentence or two to better organize and develop your argument to provide your reader with a “guide” to your argument In general, your thesis statement will accomplish these goals if you think of the thesis as the answer to the question your paper explores. How Can You Write a Good Thesis Statement? Here are some helpful hints to get you started. How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned Q: “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?”

The WWW Virtual Library How to Write an Essay Introduction (with Sample Intros) Steps Part 1 Building a Concise Introduction <img alt="Image titled Write an Essay Introduction Step 1" src=" width="728" height="546" class="whcdn">1Start with an example. <img alt="Image titled Write an Essay Introduction Step 6" src=" width="728" height="546" class="whcdn">6Transition into your first paragraph to wrap everything up. Part 2 Prewriting For Your Introduction <img alt="Image titled Write an Essay Introduction Step 7" src=" width="728" height="546" class="whcdn">1Think about your “angle” on your topic. Part 3 Tips

The World-Wide Web Virtual Library: Neuroscience (Biosciences) Writing an Introduction- CRLS Research Guide CRLS Research Guide Writing an Introduction Tip Sheet 17 Ask these questions: What is it? An introduction is the first paragraph of a written research paper, or the first thing you say in an oral presentation, or the first thing people see, hear, or experience about your project. It has two parts: 1. Why do it? Without an introduction it is sometimes very difficult for your audience to figure out what you are trying to say. When do I do it? Many books recommend writing your introduction last, after you finish your project. How do I do it? Start with a couple of sentences that introduce your topic to your reader. Then state your thesis, which may be done in one or more sentences. Some Examples: For the example, the regular text is the general introduction to the topic. Example 1 Teenagers in many American cities have been involved in more gangs in the last five years than ever before. An introduction gives the reader an idea of where you are going in your project so they can follow along.

THE BRAIN FROM TOP TO BOTTOM Our most powerful motivations come from behaviours that have proven beneficial to our species from an evolutionary standpoint. have thus evolved to give us pleasure when we engage in these behaviours. The brain has two major pathways that help to : the reward circuit, which is part of the medial forebrain bundle (MFB); and the punishment circuit, or periventricular system (PVS). Both the MFB, through the desire/action/satisfaction cycle, and the PVS, through the successful fight or flight response, lead the organism to behave in a way that preserves its homeostasis. Together, they form the behavioural approach system (BAS). Opposing the BAS is the , characterized by Henri Laborit in the early 1970s. Under natural conditions, the BIS is activated when we observe that our actions will be ineffective. For example, consider a small mammal in the middle of a field who suddenly sees a bird of prey flying overhead.

Brain mechanisms of Freudian repression – Neurophilosophy More than 100 years ago, Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, proposed a mechanism called repression, whereby desires and impulses are actively pushed into the unconscious mind. For Freud, repression was a defence mechanism - the repressed memories are often traumatic in nature, but, although hidden, they continue to exert an effect on behaviour. Many of Freud's theories have long since been discredited, but they remain influential to this day. Repression in particular has proven to be extremely controversial. Nevertheless, we now know that unwanted memories can indeed be actively forgotten, and some of the brain mechanisms underlying voluntary memory suppression have been identified. There are a number of reasons why one might want to prevent memories from entering consciousness. The new study, carried out in Karl Heinz-Bäuml's laboratory in the Department of Experimental Psychology at Regensburg University, builds on these initial findings. Related:

Does researching casual marijuana use cause brain abnormalities? In reading the news yesterday I came across multiple reports claiming that even casually smoking marijuana can change your brain. I usually don’t pay much attention to such articles; I’ve never smoked a joint in my life. In fact, I’ve never even smoked a cigarette. So even though as a scientist I’ve been interested in cannabis from the molecular biology point of view, and as a citizen from a legal point of view, the issues have not been personal. However reading a USA Today article about the paper, I noticed that the principal investigator Hans Breiter was claiming to be a psychiatrist and mathematician. J.M. This is quite possibly the worst paper I’ve read all year (as some of my previous blog posts show I am saying something with this statement). 1. First of all, the study has a very small sample size, with only 20 “cases” (marijuana users), a fact that is important to keep in mind in what follows. 2. Figure 1c. Table 4. The fact that there are multiple columns is also problematic. 3.

How curiosity changes the brain to enhance learning -- ScienceDaily The more curious we are about a topic, the easier it is to learn information about that topic. New research publishing online October 2 in the Cell Press journal Neuron provides insights into what happens in our brains when curiosity is piqued. The findings could help scientists find ways to enhance overall learning and memory in both healthy individuals and those with neurological conditions. "Our findings potentially have far-reaching implications for the public because they reveal insights into how a form of intrinsic motivation -- curiosity -- affects memory. These findings suggest ways to enhance learning in the classroom and other settings," says lead author Dr. Matthias Gruber, of University of California at Davis. For the study, participants rated their curiosity to learn the answers to a series of trivia questions. The study revealed three major findings. The findings could have implications for medicine and beyond.

Neurons can be reprogrammed to switch the emotional association of a memory Memories of experiences are encoded in the brain along with contextual and emotional information such as where the experience took place and whether it was positive or negative. This allows for the formation of memory associations that might assist in survival. Just how this positive and negative encoding occurs, however, has remained unclear. Susumu Tonegawa and colleagues from the RIKEN–MIT Center for Neural Circuit Genetics have now discovered that neurons in the hippocampus region of the brain can be artificially switched to encode memories as either positive or negative regardless of the original experience. Tonegawa's research team used genetic techniques to mark neurons in the dorsal dentate gyrus region of the hippocampus and the basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA) in male mice. The researchers then used light to activate the hippocampal or BLA neurons that had been labeled during the formation of a positive memory while exposing the mice to foot shocks.

Think Twice: How the Gut's "Second Brain" Influences Mood and Well-Being As Olympians go for the gold in Vancouver, even the steeliest are likely to experience that familiar feeling of "butterflies" in the stomach. Underlying this sensation is an often-overlooked network of neurons lining our guts that is so extensive some scientists have nicknamed it our "second brain". A deeper understanding of this mass of neural tissue, filled with important neurotransmitters, is revealing that it does much more than merely handle digestion or inflict the occasional nervous pang. The little brain in our innards, in connection with the big one in our skulls, partly determines our mental state and plays key roles in certain diseases throughout the body. Although its influence is far-reaching, the second brain is not the seat of any conscious thoughts or decision-making. This multitude of neurons in the enteric nervous system enables us to "feel" the inner world of our gut and its contents. The second brain informs our state of mind in other more obscure ways, as well.

10 Marvin Minsky Quotes That Reflect What a Visionary He Was Twenty years ago, when I was first imagining "Closer To Truth," our public television series on science and philosophy, and fantasizing about who might appear, Marvin Minsky was one of a small handful of world-renowned thinkers on my A+ wish list. Luckily, he said yes -- and then yes again. Marvin, who died Sunday at age 88, was visionary, pioneering, substantive, rigorous, tough-minded, iconoclastic, daring and whimsical. I wanted to do what Marvin did: challenge conventional belief, taking our topics seriously but never ourselves. Here are some quotes illustrating the unique insights Minsky provided during our discussions over the years, followed by links back to the videos. It's perfectly possible that we are the production of some very powerful complicated programs running on some big computer somewhere else. If we are simulated, we might find some technique that would notice some of the grain of the computer being used is showing through a little bit. We're in a possible world.

The Smell Report - The human sense of smell. Although the human sense of smell is feeble compared to that of many animals, it is still very acute. We can recognise thousands of different smells, and we are able to detect odours even in infinitesimal quantities. Our smelling function is carried out by two small odour-detecting patches – made up of about five or six million yellowish cells – high up in the nasal passages. For comparison, a rabbit has 100 million of these olfactory receptors, and a dog 220 million. Humans are nonetheless capable of detecting certain substances in dilutions of less than one part in several billion parts of air. We may not be able to match the olfactory feats of bloodhounds, but we can, for example, ‘track’ a trail of invisible human footprints across clean blotting paper. The human nose is in fact the main organ of taste as well as smell. Variations Our smelling ability increases to reach a plateau at about the age of eight, and declines in old age. Children