Abhijna

Supernormal knowledge in Buddhism Abhijñā (Sanskrit: अभिज्ञा; Pali pronunciation: abhiññā; Standard Tibetan: མངོན་ཤེས mngon shes; Chinese: 六通/神通/六神通; pinyin: Liùtōng/Shéntōng/Liùshéntōng; Japanese: 六神通, romanized: Rokujinzū/Rokujintsū) is a Buddhist term generally translated as "direct knowledge",[1] "higher knowledge"[2][3] or "supernormal knowledge."[2][4] In Buddhism, such special knowledge is obtained through virtuous living and meditation. The attainment of the four jhanas, or meditative absorptions, is considered a prerequisite for their attainment. In Pali literature, abhiññā refers to both the direct apprehension of dhamma (translated below as "states" and "qualities") as well as to specialized super-normal capabilities. Direct knowing of dhamma [edit] In SN 45.159, the Buddha describes "direct knowledge" (abhiññā) as a corollary to the pursuit of the Noble Eightfold Path:[3] What, monks, are the states to be comprehended with direct knowledge? Enumerations of special knowledges

Samadhi

Un article de Wikipédia, l'encyclopédie libre. Samādhi (समाधि en sanskrit devanāgarī)[1] est un terme sanskrit qui est lié à la philosophie indienne. Il correspond dans les Yoga Sūtra de Patañjali au huitième membre (aṅga) du Yoga. Il signifie complet (sam-) établissement, maintien, « reposition » (-ādhi) de la conscience, de l'attention. Son usage généralisé a entraîné un important élargissement sémantique: ce substantif masculin signifie « union, totalité, accomplissement, achèvement, mise en ordre, rangement, concentration totale de l’esprit, contemplation, absorption[2] ». Le samādhi dans la tradition bouddhique[modifier | modifier le code] Le samādhi en tant que concentration[modifier | modifier le code] En tant que concentration, le samādhi est associé à la pratique de méditation appelée samatha bhavana, le développement de la tranquillité. Plusieurs niveaux de concentrations sont distingués : Concentration grossière, ou préliminaire (parikamma samādhi) Ou concentration de proximité.

Kundalini syndrome

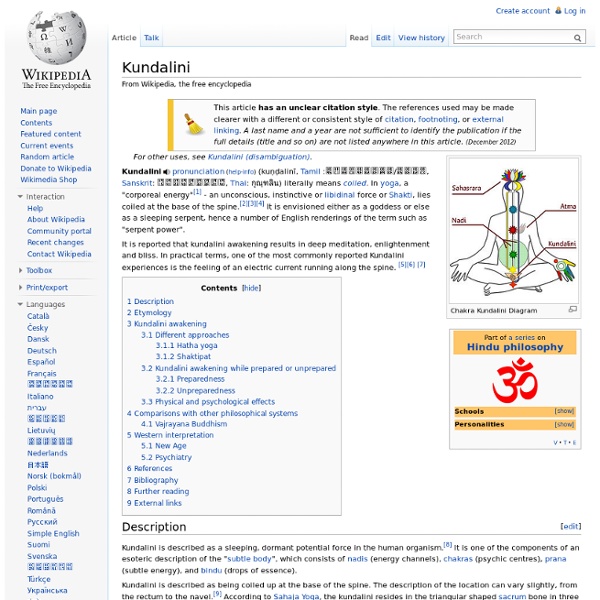

The Kundalini syndrome is a set of sensory, motor, mental and affective experiences described in the literature of transpersonal psychology, near-death studies and other sources covering transpersonal, spiritual or medical topics. The phenomenon is sometimes called the "Kundalini-syndrome",[1][2][3] the "Physio-Kundalini syndrome",[4][5][6][7] or simply referred to as a "syndrome".[8][9] Other researchers, while not using the term "syndrome",Note a have also begun to address this phenomenon as a clinical category,[10][11] or as a recognizable symptomatology.[12] The concept of Kundalini comes from Hinduism and is traditionally used to describe a progression of psycho-spiritual potentials, associated with the understanding of the body as a vehicle for spiritual energies. Terminology[edit] Commentators seem to use different terms when describing the symptomatology and phenomenology of kundalini. Symptomatology[edit] The Kundalini Scale[edit] The Physio-Kundalini Syndrome Index[edit]

Six Yogas of Naropa

The Six Yogas of Nāropa (Tib. Narö chö druk, na-ro'i-chos-drug), also called the six dharmas of Naropa.[1] Naro's six doctrines (Mandarin: Ming Xing Dao Liu Cheng Jiu Fa; rendered in English as: Wisdom Activities Path Six Methods of Accomplishment),[2] are a set of advanced Indo-Tibetan Buddhist tantric practices and a meditation sādhana compiled in and around the time of the Indian monk and mystic Nāropa (1016-1100 CE) and conveyed to his student Marpa the translator. The six yogas were intended in part to help in the attainment of siddhi and enlightenment in an accelerated manner. Six Yogas or Six Dharmas?[edit] Peter Alan Roberts notes that the proper terminology is "six Dharmas of Nāropa", not "six yogas of Nāropa": "Tilopa briefly described these six practices in a short verse text entitled Instructions on the Six Dharmas. Classification[edit] The six Dharmas are a synthesis or collection of the completion stage practices of several tantras. The six yogas[edit] Physical exercises[edit]

Qi (spiritualité)

Un article de Wikipédia, l'encyclopédie libre. Pour les articles homonymes, voir Qi et Ki. Le qi [tɕʰi˥˩] (chinois simplifié : 气 ; chinois traditionnel : 氣 ; pinyin : qì ; Wade : ch'i⁴ ; EFEO : ts'i), ou ki [xǐ] (japonais : 気), ou encore chi, est une notion des cultures chinoise et japonaise qui désigne un principe fondamental formant et animant l'univers et la vie[1],[2],[3],[4]. Le qi est un concept hypothétique[5]. La notion qi n'a aucun équivalent précis en Occident. Apparaissent toutefois de nombreux liens de convergence avec la notion grecque de πνεῦμα / pneûma (« souffle »), et dans la même optique avec la notion d'esprit (en latin « spiritus » dérivé de spirare, souffler), qui signifie souffle, vent. Plusieurs concepts de la philosophie indienne s'en rapprochent, tels que le prana (प्राण / prāṇa) ou l'ojas (ओजस् / ojas). Le qi reste difficile à traduire. Les brumes en montagne (Tang Yifen, 1849) L'oiseau observe des poissons (Gao Qipei, 1713) Dāntián inférieur (下丹田)

Meditation Forum

Skandha

In the Theravada tradition, suffering arises when one identifies with or clings to an aggregate. Suffering is extinguished by relinquishing attachments to aggregates. The Mahayana tradition further puts forth that ultimate freedom is realized by deeply penetrating the nature of all aggregates as intrinsically empty of independent existence. Etymology[edit] Outside of Buddhist didactic contexts, "skandha" can mean mass, heap, pile, gathering, bundle or tree trunk.[3][c] According to Thanissaro, the buddha gave a new meaning to the term "khanda": Prior to the Buddha, the Pali word khandha had very ordinary meanings: A khandha could be a pile, a bundle, a heap, a mass. Description in the Sutta Pitaka[edit] The Sutta Pitaka of the Pali Canon contains the teachings of the Buddha, as preserved by the Theravada tradition. The five skandhas[edit] The sutras describe five aggregates:[d] Suffering and release[edit] Understanding dukkha[edit] Clinging causes future suffering[edit] ... No essence[edit]

YOGA, HATHA-YOGA et TANTRISME. Vidéos, photos, fiches techniques

Samaññaphala Sutta

The Samaññaphala Sutta is the second discourse (Pali, sutta; Skt., sutra) of all 34 Digha Nikaya discourses. The title means, "The Fruit of Contemplative Life Discourse." In terms of narrative, this discourse tells the story of King Ajatasattu, son and successor of King Bimbisara of Magadha, who posed the following question to many leading Indian spiritual teachers: What is the benefit of living a contemplative life? After being dissatisfied with the answers provided by these other teachers, the king posed this question to the Buddha whose answer motivated the king to become a lay follower of the Buddha. In terms of Indian philosophy and spiritual doctrines, this discourse: Thanissaro (1997) refers to this discourse as "one of the masterpieces of the Pali canon The king's unrest[edit] The King immediately agreed to go there. To answer his majesty's paranoia, the physician calmly reassured the monarch, "Do not worry, your Majesty. The King then approached the Buddha and gave his salutation.