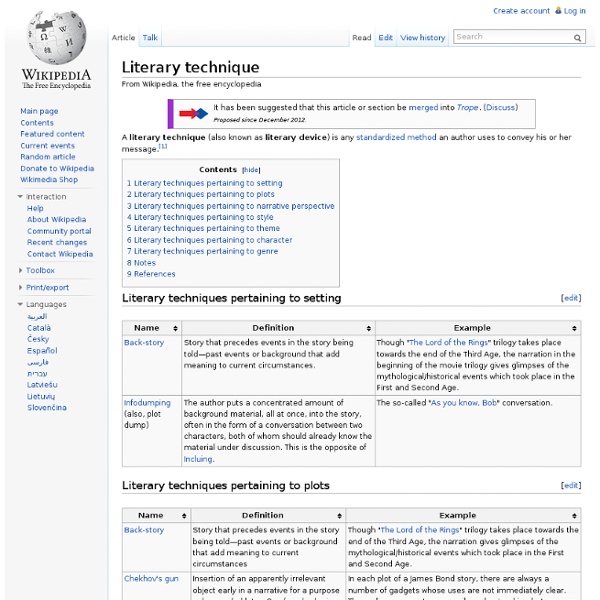

Literary technique

A literary technique (also known as literary device) is any method an author uses to convey his or her message.[1] This distinguishes them from literary elements, which exist inherently in literature. Literary techniques pertaining to setting[edit] Literary techniques pertaining to plots[edit] Literary techniques pertaining to narrative perspective[edit] Literary techniques pertaining to style[edit] Literary techniques pertaining to theme[edit] Literary techniques pertaining to character[edit] Literary techniques pertaining to genre[edit] Notes[edit] Jump up ^ Orehovec, Barbara (2003). References[edit] Heath, Peter (May 1994), "Reviewed work(s): Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights by David Pinault", International Journal of Middle East Studies (Cambridge University Press) 26 (2): 358–360

Imagery

Imagery, in a literary text, is an author's use of vivid and descriptive language to add depth to his or her work. It appeals to human senses to deepen the reader's understanding of the work. Forms of imagery[edit] There are seven types of imagery, each corresponding to a human sense, feeling, or action: Visual imagery pertains to sight, and allows you to visualize events or places in a work.Auditory imagery pertains to a sound. See also[edit] (examples of imagery) References[edit] External links[edit]

Author's Craft - Narrative Elements - Foreshadowing

Narrative Elements Foreshadowing What is it? Foreshadowing is a way of indicating or hinting at what will come later. Foreshadowing can be subtle, like storm clouds on the horizon suggesting that danger is coming, or more direct, such as Romeo and Juliet talking about wanting to die rather than live without each other. Sometimes authors use false clues to mislead a reader. Why is it important? Foreshadowing adds dramatic tension to a story by building anticipation about what might happen next. How do I create it? Create foreshadowing by placing clues, both subtle and direct, into the text. To create foreshadowing in fiction or non-fiction, Give the reader direct information by mentioning an upcoming event or explaining the plans of the people or characters portrayed in the text: "As the Lincolns rode to Ford's Theatre on 10th Street, John Wilkes Booth and three conspirators were a block away at the Herndon House. Self Check Example Foreshadowing Tip

Scholastic- Craft Writing

by Brenda Power Supporting children in honing their writing craft can be daunting because most of us don't feel accomplished ourselves as writers. That's why focusing on beginnings and endings works so well: it's concrete and manageable. The approaches outlined in this cover story are favorites of the teachers I visit, and are easily adapted for students of any age. In this article, you'll find: A kiss hello...a wave good-bye...an airplane fading in the sky. Our lives are marked by beginnings and endings. The best leads and endings don't just happen; they are crafted. If you take some time to make leads and endings the focus of your lessons, youmay be surprised at how quickly students' overall writing skills improve. l. Together, you may also want to create separate charts for beginnings and endings.Classify the beginnings you read according to whether they contain dialogue, a "climactic moment," helpful introductory information, or other categories you discover through reading. 2. 3. 4.

30 Ideas for Teaching Writing

Summary: Few sources available today offer writing teachers such succinct, practice-based help—which is one reason why 30 Ideas for Teaching Writing was the winner of the Association of Education Publishers 2005 Distinguished Achievement Award for Instructional Materials. The National Writing Project's 30 Ideas for Teaching Writing offers successful strategies contributed by experienced Writing Project teachers. Since NWP does not promote a single approach to teaching writing, readers will benefit from a variety of eclectic, classroom-tested techniques. These ideas originated as full-length articles in NWP publications (a link to the full article accompanies each idea below). Table of Contents: 30 Ideas for Teaching Writing 1. Debbie Rotkow, a co-director of the Coastal Georgia Writing Project, makes use of the real-life circumstances of her first grade students to help them compose writing that, in Frank Smith's words, is "natural and purposeful." ROTKOW, DEBBIE. 2003. Back to top 2. 3. 4.

Related:

Related: