Giordano Bruno

Artigo Pág. 5 Giordano Bruno: O homem, o mundo e o Renascimento Giordano Bruno apresenta uma das teorias filosóficas mais complexas de todos os tempos e é assim tido, inclusive por Giovanne Reale. Escreveu sobre muitas questões, desde a magia até a matemática. Firmou-se como um místico em suas interpretações do mundo, mas sua principal contribuição veio na sua teoria da infinitude do Universo, em que apresenta, também, uma visão teológica panteísta. Para Bruno, o homem jamais poderá conhecer Deus, posto que ele está além da capacidade do pensamento humano. No seu entendimento, Deus está acima da esfera do nosso pensamento, sendo mais relevante chegar a ele pela revelação do que pela inteligência. Observa-se, ainda, que Giordano Bruno faz uma distinção entre príncipio e causa. A resposta para a questão do princípio, o autor encontra não em Aristóteles, como era comum na época, mas nos pré-socráticos, filósofos da natureza por excelência. Distingue ser (todo) de modos de ser (coisas).

giordano

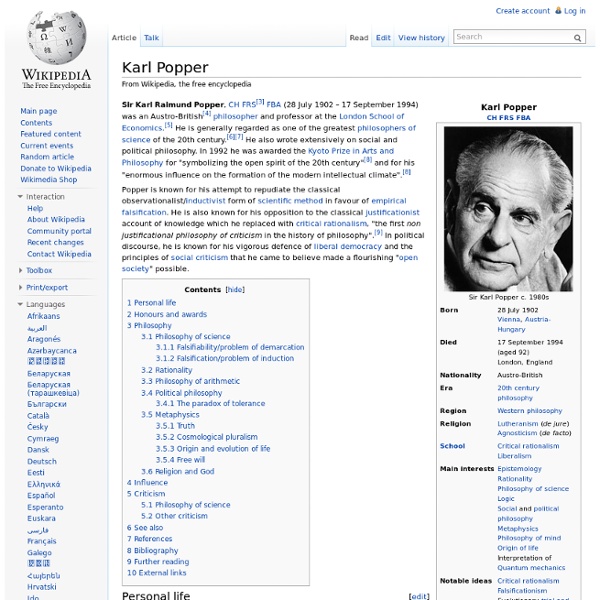

► Texto de ANTÓNIO MARINHO, talvez no semanário «O Expresso» Por ter adoptado a Teoria de Copérnico, segundo a qual a Terra e os outros planetas giram à volta do Sol, e admitido a infinitude do Universo, além de uma infinidade de mundos, Giordano Bruno foi queimado vivo pela Inquisição. O episódio ocorreu a 17 de Fevereiro de 1600, em Roma Completaram-se na quinta-feira, dia 17, 400 anos sobre a morte de Giordano Bruno, queimado vivo pela Inquisição devido às suas teses filosóficas e científicas. Nascido em Itália, na localidade de Nola (Campânia), em 1548, Giordano Bruno era sobretudo um inconformado e um insatisfeito que percorreu a Europa do seu tempo ensinando em algumas das mais famosas universidades de então, tais como Toulouse, Paris, Oxford, Witemberg e Zurique. Retrato de Giordano Bruno publicado numa edição da Gulbenkian, em Janeiro de 1978 A sua personalidade e as suas doutrinas estiveram sempre envolvidas por uma controvérsia que perdura até aos nossos dias.

GIORDANO BRUNO CONDENADO PELAS IDÉIAS DE COPÉRNICO « Caiafarsa

A MENTIRA:.1594d > Igreja: Na Itália, na Igreja Católica, o padre Giordano Bruno, de filosofia, preso em nome do papa, por apoiar as teorias de Nicolau Copérnico Site Batista: Os acusadores citam a condenação de Giordano Bruno para “comprovar” a contradição Católica, afirmando que este foi condenado por defender as idéias do Padre Copérnico..A VERDADE DOCUMENTAL: Quem tem o mínimo de conhecimento histórico sabe que Giordano Bruno não foi condenado por sua defesa do sistema Copérnico como afirma os mentirosos, nem por sua teoria da pluralidade dos mundos habitados, mas por sua idéias teológicas repletas de erros, este afirmava, por exemplo, que Cristo não era Deus e sim um hábil mágico, que o espírito santo era a alma do mundo e que o Diabo seria salvo. Suas idéias e concepções: “O princípio do mundo infinito obriga Bruno a supor que o princípio do mundo não está fora dele, mas é força que está dentro dele.

Giordano Bruno

Origem: Wikipédia, a enciclopédia livre. Giordano Bruno (Nola, Reino de Nápoles, 15482 — Roma, Campo de Fiori, 17 de fevereiro de 1600) foi um teólogo, filósofo, escritor e frade dominicano italiano [carece de fontes] condenado à morte na fogueira pela Inquisição romana (Congregação da Sacra, Romana e Universal Inquisição do Santo Ofício) por heresia.1 É também referido como Bruno de Nola ou Nolano.3 Notas biográficas[editar | editar código-fonte] Origem e formação[editar | editar código-fonte] Filho do militar Giovanni Bruno e Fraulissa Savolino,4 seu nome de batismo era Filippo Bruno.2 Adotou o nome de Giordano quando ingressou na Ordem Dominicana, aos 15 anos de idade.2 No seminário, estudou Aristóteles e Tomás de Aquino, predominantes na doutrina Católica da época, doutorando-se em Teologia. Suas ideias avançadas, porém, suscitaram suspeitas por parte da hierarquia da Igreja. Iniciou-se, então, o período de peregrinação de sua vida. Ideário[editar | editar código-fonte] Notas Referências

The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1972, 3rd edn.) that the nature of scientific method is hypothetico–deductive and not, as is generally believed, inductive. by raviii Aug 13