Chinese herbology

Dried herbs and plant portions for Chinese herbology at a Xi'an market Chinese herbology (simplified Chinese: 中药学; traditional Chinese: 中藥學; pinyin: zhōngyào xué) is the theory of traditional Chinese herbal therapy, which accounts for the majority of treatments in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). The term herbology is misleading in the sense that, while plant elements are by far the most commonly used substances, animal, human, and mineral products are also utilized. Thus, the term "medicinal" (instead of herb) is usually preferred as a translation for 药 (pinyin: yào).[1] The effectiveness of traditional Chinese herbal therapy remains poorly documented.[2] There are concerns over a number of potentially toxic Chinese herbs.[3] History[edit] Chinese pharmacopoeia Chinese herbs have been used for centuries. The first traditionally recognized herbalist is Shénnóng (神农, lit. Raw materials[edit] Some animal parts used as medicinals can be considered rather strange such as cows' gallstones.[12]

Feng Shui Shopper

Marina Lighthouse and Feng Shui Shopper presents Monthly Treasures March/April 2014 Feng Shui Newsletter “How a person masters his fate is more important than what his fate is.”~ Karl Wilhelm von Humboldt Divination and Inspiration: The I Ching A great source of guidance can be found in one of the oldest books on earth; the I Ching or Book of Changes. Ultimately this became a system based on the energy movements of Yin represented by broken lines and Yang solid lines. How to Use The I Ching or The Book of Changes for Divination Through the years readings were condensed to tossing three coins. ). ). The hexagram is divided into two trigrams; the bottom three lines are called the lower trigram; the top three lines are the upper trigram; together they create the 64 hexagrams below. Find the number and then look up the meaning here. The I Ching or Book of Changes is a wonderful resource to help understand the ebbs and flows of life. H. Enjoy and have a beautiful blossoming productive Spring!

Yin and yang

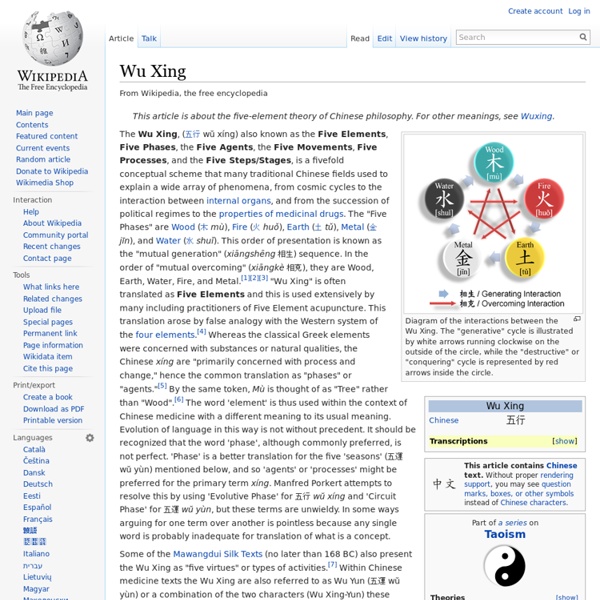

In Chinese philosophy, the concept of yin-yang (simplified Chinese: 阴阳; traditional Chinese: 陰陽; pinyin: yīnyáng), which is often called "yin and yang",[1][2][3][4] is used to describe how opposite or contrary forces are interconnected and interdependent in the natural world; and, how they give rise to each other as they interrelate to one another. Many natural dualities (such as light and dark, high and low, hot and cold, fire and water, life and death, male and female, sun and moon, and so on) are thought of as physical manifestations of the yin-yang concept. The concept lies at the origins of many branches of classical Chinese science and philosophy, as well as being a primary guideline of traditional Chinese medicine,[5] and a central principle of different forms of Chinese martial arts and exercise, such as baguazhang, taijiquan (t'ai chi), qigong (Chi Kung), and I Ching. Nature[edit] Toponymy[edit] Classically, when used in place names, yang refers to the "sunny side." I Ching[edit]

Feng Shui Store

Kōan

A kōan (公案?)/ˈkoʊ.ɑːn/; Chinese: 公案; pinyin: gōng'àn; Korean: 공안 (kong'an); Vietnamese: công án) is a story, dialogue, question, or statement, which is used in Zen-practice to provoke the "great doubt", and test a student's progress in Zen practice. Etymology[edit] According to the Yuan Dynasty Zen master Zhongfeng Mingben (中峰明本 1263–1323), gōng'àn originated as an abbreviation of gōngfǔ zhī àndú (公府之案牘, Japanese kōfu no antoku—literally the andu "official correspondence; documents; files" of a gongfu "government post"), which referred to a "public record" or the "case records of a public law court" in Tang-dynasty China. Commentaries in kōan collections bear some similarity to judicial decisions that cite and sometimes modify precedents. Gong'an was itself originally a metaphor—an article of furniture that came to denote legal precedents. Origins and development[edit] China[edit] [edit] Those stories came to be known as gongan, "public cases". Literary practice[edit] Interaction[edit]

Bazi Fengshui