Brain Atlas - Introduction The central nervous system (CNS) consists of the brain and the spinal cord, immersed in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Weighing about 3 pounds (1.4 kilograms), the brain consists of three main structures: the cerebrum, the cerebellum and the brainstem. Cerebrum - divided into two hemispheres (left and right), each consists of four lobes (frontal, parietal, occipital and temporal). – closely packed neuron cell bodies form the grey matter of the brain. Cerebellum – responsible for psychomotor function, the cerebellum co-ordinates sensory input from the inner ear and the muscles to provide accurate control of position and movement. Brainstem – found at the base of the brain, it forms the link between the cerebral cortex, white matter and the spinal cord. Other important areas in the brain include the basal ganglia, thalamus, hypothalamus, ventricles, limbic system, and the reticular activating system. Basal Ganglia Thalamus and Hypothalamus Ventricles Limbic System Reticular Activating System Glia

Functional magnetic resonance imaging Researcher checking fMRI images Functional magnetic resonance imaging or functional MRI (fMRI) is a functional neuroimaging procedure using MRI technology that measures brain activity by detecting associated changes in blood flow.[1] This technique relies on the fact that cerebral blood flow and neuronal activation are coupled. When an area of the brain is in use, blood flow to that region also increases. The primary form of fMRI uses the Blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) contrast,[2] discovered by Seiji Ogawa. The procedure is similar to MRI but uses the change in magnetization between oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood as its basic measure. FMRI is used both in the research world, and to a lesser extent, in the clinical world. Overview[edit] The fMRI concept builds on the earlier MRI scanning technology and the discovery of properties of oxygen-rich blood. History[edit] Three studies in 1992 were the first to explore using the BOLD contrast in humans. Physiology[edit]

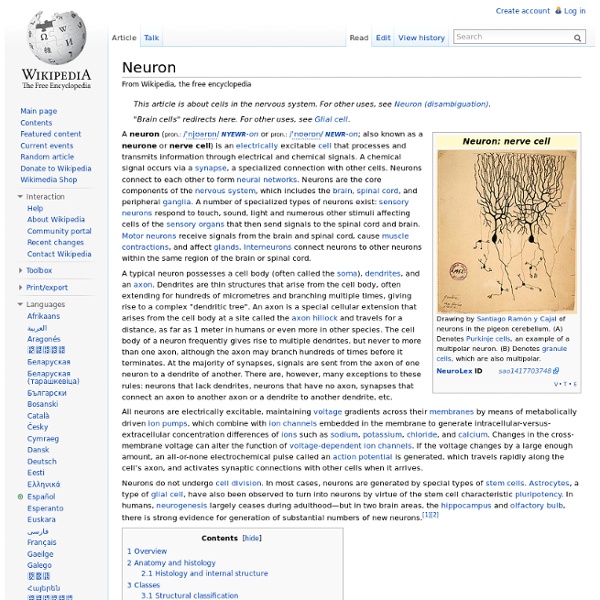

UCSB scientists discover how the brain encodes memories at a cellular level (Santa Barbara, Calif.) –– Scientists at UC Santa Barbara have made a major discovery in how the brain encodes memories. The finding, published in the December 24 issue of the journal Neuron, could eventually lead to the development of new drugs to aid memory. The team of scientists is the first to uncover a central process in encoding memories that occurs at the level of the synapse, where neurons connect with each other. "When we learn new things, when we store memories, there are a number of things that have to happen," said senior author Kenneth S. "One of the most important processes is that the synapses –– which cement those memories into place –– have to be strengthened," said Kosik. This is a neuron. (Photo Credit: Sourav Banerjee) Part of strengthening a synapse involves making new proteins. The production of new proteins can only occur when the RNA that will make the required proteins is turned on. When the signal comes in, the wrapping protein degrades or gets fragmented.

Diffusion MRI Diffusion MRI (or dMRI) is a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) method which came into existence in the mid-1980s.[1][2][3] It allows the mapping of the diffusion process of molecules, mainly water, in biological tissues, in vivo and non-invasively. Molecular diffusion in tissues is not free, but reflects interactions with many obstacles, such as macromolecules, fibers, membranes, etc. Water molecule diffusion patterns can therefore reveal microscopic details about tissue architecture, either normal or in a diseased state. The first diffusion MRI images of the normal and diseased brain were made public in 1985.[4][5] Since then, diffusion MRI, also referred to as diffusion tensor imaging or DTI (see section below) has been extraordinarily successful. In diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), the intensity of each image element (voxel) reflects the best estimate of the rate of water diffusion at that location. Diffusion[edit] Given the concentration and flux where D is the diffusion coefficient.

The Learning Brain Gets Bigger--Then Smaller With age and enough experience, we all become connoisseurs of a sort. After years of hearing a favorite song, you might notice a subtle effect that’s lost on greener ears. Perhaps you’re a keen judge of character after a long stint working in sales. Or maybe you’re one of the supremely practiced few who tastes his money’s worth in a wine. Whatever your hard-learned skill is, your ability to hear, see, feel, or taste with more nuance than a less practiced friend is written in your brain. One classical line of work has tackled these questions by mapping out changes in brain organization following intense and prolonged sensory experience. But don’t adopt that slogan quite yet. If you were to look at the side of someone’s brain, focusing on the thin sliver of auditory cortex, it would seem fairly uniform, with only a few blood vessels to provide some bearing. And yet, some aspects of this theory invited skepticism. So what does change? Still, there’s a big question lurking here.

Episodes - Brain Science Podcast Episode 1-10 can now be purchased for download as a single zip file. Other episodes and transcripts may be purchased separately. Please see the episode show notes for links. Mind Wide Open: A general introduction to why neuroscience matters, based on Mind Wide Open: Your Brain and the Neuroscience of Everyday Life, by Steven Johnson. On Intelligence: A discussion of On Intelligence, by Jeff Hawkins.

Meditation found to increase brain size Kris Snibbe/Harvard News Office Sara Lazar (center) talks to research assistant Michael Treadway and technologist Shruthi Chakrapami about the results of experiments showing that meditation can increase brain size. People who meditate grow bigger brains than those who don’t. Researchers at Harvard, Yale, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have found the first evidence that meditation can alter the physical structure of our brains. Brain scans they conducted reveal that experienced meditators boasted increased thickness in parts of the brain that deal with attention and processing sensory input. In one area of gray matter, the thickening turns out to be more pronounced in older than in younger people. “Our data suggest that meditation practice can promote cortical plasticity in adults in areas important for cognitive and emotional processing and well-being,” says Sara Lazar, leader of the study and a psychologist at Harvard Medical School. Controlling random thoughts

Electroencephalography Simultaneous video and EEG recording of two guitarists improvising. Electroencephalography (EEG) is the recording of electrical activity along the scalp. EEG measures voltage fluctuations resulting from ionic current flows within the neurons of the brain.[1] In clinical contexts, EEG refers to the recording of the brain's spontaneous electrical activity over a short period of time, usually 20–40 minutes, as recorded from multiple electrodes placed on the scalp. Diagnostic applications generally focus on the spectral content of EEG, that is, the type of neural oscillations that can be observed in EEG signals. EEG is most often used to diagnose epilepsy, which causes obvious abnormalities in EEG readings.[2] It is also used to diagnose sleep disorders, coma, encephalopathies, and brain death. History[edit] Hans Berger In 1934, Fisher and Lowenback first demonstrated epileptiform spikes. In 1947, The American EEG Society was founded and the first International EEG congress was held.

Imagining the Future Invokes Your Memory I REMEMBER my retirement like it was yesterday. As I recall, I am still working, though not as hard as I did when I was younger. My wife and I still live in the city, where we bicycle a fair amount and stay fit. We have a favorite coffee shop where we read the morning papers and say hello to the other regulars. In reality, I’m not even close to retirement. A new study from the January issue of Psychological Science may explain why we are all so optimistic about what’s to come. Cognitive scientists are very interested in people’s “remembered futures.” Still, very little was known until recently about how these simulations work. These are very difficult questions to study in a laboratory—or at least they were until now. Recalling Tomorrow Szpunar and his colleagues began by collecting a lot of biographical detail from volunteers’ actual memories.

The Brain May Disassemble Itself in Sleep Compared with the hustle and bustle of waking life, sleep looks dull and unworkmanlike. Except for in its dreams, a sleeping brain doesn’t misbehave or find a job. It also doesn’t love, scheme, aspire or really do much we would be proud to take credit for. In a provocative new theory about the purpose of sleep, neuroscientist Giulio Tononi of the University of Wisconsin–Madison has proposed that slumber, to cement what we have learned, must also spur the brain’s undoing. Select an option below: Customer Sign In *You must have purchased this issue or have a qualifying subscription to access this content

Is the Purpose of Sleep to Let Our Brains “Defragment,” Like a Hard Drive? | The Crux Neuroskeptic is a neuroscientist who takes a skeptical look at his own field and beyond at the Neuroskeptic blog. Why do we sleep? We spend a third of our lives doing so, and all known animals with a nervous system either sleep, or show some kind of related behaviour. But scientists still don’t know what the point of it is. There are plenty of theories. Some researchers argue that sleep has no specific function, but rather serves as evolution’s way of keeping us inactive, to save energy and keep us safely tucked away at those times of day when there’s not much point being awake. But others argue that sleep has a restorative function—something about animal biology means that we need sleep to survive. Waking up after a good night’s sleep, you feel restored, and many studies have shown the benefits of sleep for learning, memory, and cognition. This illustration, taken from their paper, shows the basic idea: While we’re awake, your brain is forming memories. So what’s the evidence?

Making Sense of the World, Several Senses at a Time Our five senses–sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell–seem to operate independently, as five distinct modes of perceiving the world. In reality, however, they collaborate closely to enable the mind to better understand its surroundings. We can become aware of this collaboration under special circumstances. In some cases, a sense may covertly influence the one we think is dominant. When visual information clashes with that from sound, sensory crosstalk can cause what we see to alter what we hear. Our senses must also regularly meet and greet in the brain to provide accurate impressions of the world. Seeing What You Hear We can usually differentiate the sights we see and the sounds we hear. Beep Baseball Blind baseball seems almost an oxymoron. Calling What You See Bats and whales, among other animals, emit sounds into their surroundings—not to communicate with other bats and whales—but to “see” what is around them. Do You Have Synesthesia?