Why does the Strait of Hormuz matter? News BBC News Navigation Sections Previous Next Media player Media playback is unsupported on your device Jump media player Media player help.

Arctic permafrost might contain 'sleeping giant' of world's carbon emissions. As temperatures rise in the Arctic, permafrost, or frozen ground, is thawing.

As it does, greenhouse gases trapped within it are being released into the atmosphere in the form of carbon dioxide and methane, leading to previously underestimated problems with ocean acidification and potential mercury poisoning. About one quarter of the region is covered in permafrost, which is soil, sediment or rock that has been frozen for at least two years. With its retreat, the carbon that is released could contribute significantly to global warming. A journey underground into one of Poland's working mines.

Terrestrial Carbon Cycle. Prof Ray Wills sur Twitter : "Prediction is difficult, especially about the future. In 2010, world saw large role for #biomass in future #renewables generation In 2018, clear biomass will only play a minor role But #wind and #solar growth far greater than. Turning carbon dioxide into rock - forever. Image copyright G Svanberg.

*Carbon cycle (Iain Stewart): BBC Taster - Bitesize Masterclass No.2. Scientists have long feared this ‘feedback’ to the climate system. Now they say it’s happening. World's largest peatland with vast carbon-storage capacity found in Congo. Scientists have discovered the world’s largest tropical peatland in the remote Congo swamps, estimated to store the equivalent of three year’s worth of the world’s total fossil fuel emissions.

Researchers mapped the Cuvette Centrale peatlands in the central Congo basin and found they cover 145,500 sq km – an area larger than England. The swamps could lock in 30bn tonnes of carbon that was previously not known to exist, making the region one of the most carbon-rich ecosystems on Earth. The UK-Congolese research team, co-led by Prof Simon Lewis and Dr Greta Dargie, from the University of Leeds and University College London, first discovered the swamps five years ago. New research says it just might be possible:'Greater soil carbon stocks and faster turnover rates with increasing agricultural productivity' New paper by @duarteoceans: Export from #Seagrass Meadows Contributes to Marine Carbon Sequestration #Bluecarbon. Living Planet: Saving Scotland′s peat bogs.

Share.

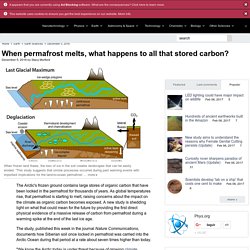

When permafrost melts, what happens to all that stored carbon? The Arctic's frozen ground contains large stores of organic carbon that have been locked in the permafrost for thousands of years.

As global temperatures rise, that permafrost is starting to melt, raising concerns about the impact on the climate as organic carbon becomes exposed. A new study is shedding light on what that could mean for the future by providing the first direct physical evidence of a massive release of carbon from permafrost during a warming spike at the end of the last ice age. The study, published this week in the journal Nature Communications, documents how Siberian soil once locked in permafrost was carried into the Arctic Ocean during that period at a rate about seven times higher than today. "We know the Arctic today is under threat because of growing climate warming, but we don't know to what extent permafrost will respond to this warming. *****Permafrost degradation: In Siberia there is a huge crater and it is getting bigger.

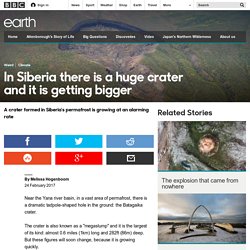

Near the Yana river basin, in a vast area of permafrost, there is a dramatic tadpole-shaped hole in the ground: the Batagaika crater.

The crater is also known as a "megaslump" and it is the largest of its kind: almost 0.6 miles (1km) long and 282ft (86m) deep. But these figures will soon change, because it is growing quickly. Gas Hydrate Breakdown Unlikely to Cause Massive Greenhouse Gas Release. Release Date: February 9, 2017 A recent interpretive review of scientific literature performed by the U.S.

Geological Survey and the University of Rochester sheds light on the interactions of gas hydrates and climate. The breakdown of methane hydrates due to warming climate is unlikely to lead to massive amounts of methane being released to the atmosphere, according to a recent interpretive review of scientific literature performed by the U.S.

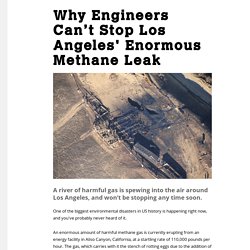

Geological Survey and the University of Rochester. Methane hydrate, which is also referred to as gas hydrate, is a naturally-occurring, ice-like form of methane and water that is stable within a narrow range of pressure and temperature conditions. On a global scale, gas hydrate deposits store enormous amounts of methane at relatively shallow depths, making them particularly susceptible to the changes in temperature that accompany climate change. Why Engineers Can’t Stop Los Angeles' Enormous Methane Leak - Motherboard. One of the biggest environmental disasters in US history is happening right now, and you've probably never heard of it.

An enormous amount of harmful methane gas is currently erupting from an energy facility in Aliso Canyon, California, at a startling rate of 110,000 pounds per hour. The gas, which carries with it the stench of rotting eggs due to the addition of a chemical called mercaptan, has led to the evacuation 1,700 homes so far. Many residents have already filed lawsuits against the company that owns the facility, the Southern California Gas Company. Footage taken on December 17 shows a geyser of methane gas spewing from the Earth, visible by a specialized infrared camera operated by an Earthworks ITC-certified thermographer. *****Photosynthesis in the U.S. Corn Belt. During peak growing season, it produces more oxygen than the Amazon! *****A year in the life of Earth’s CO2, beautiful work by @nasa. *****The carbon cycle (explainer video) *****Ultimate bogs: how saving peatlands could help save the planet.

Randy Kolka hands me a fist-sized clump of brownish-black material pulled up by an auger from a bog.

It’s the color and texture of moist chocolate cake. When I look closely I can see filaments of plant material. This hunk of peat, pulled from two meters (7ft) below the surface, is about 8,000 years old. I’m holding plants that lived and died before the Egyptians constructed the pyramids and before humans invented the wheel. In my hand is history. “That’s the oldest [from this bog] right there,” says Kolka, a soil scientist with the USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station. Two hundred miles north of Minneapolis, I’m visiting the Marcell Experimental Forest, which has conducted research on northern Minnesota peatlands since 1960 and today conducts some of the world’s leading research into how peatlands, and their vast carbon stores, might react to a warming world. Essential but long overlooked “Many countries still do not know if they have peatlands,” Christophersen says.

Under threat. Linking water and carbon cycles - the role of small streams #geographyteacher. Satellites are giving us a commanding view of Earth's carbon cycle. *****WMO releases Greenhouse Gas report at 1000 GMT on concentrations of CO2 and other heat-trapping gases in atmosphere in 2016 #COP23. Scottish lochs 'important stores' of carbon. Image copyright Tern TV/BBC Scotland Scotland's sea lochs play an important role in storing carbon which would otherwise contribute to climate change, scientists have suggested. Using samples from Loch Etive, near Oban, researchers calculated that a square metre of sediment contains more carbon than peatlands. Fernanda Adame sur Twitter : "How much carbon is lost after mangrove clearing? How long does it take to recover? Read in our new publication how to reduce emissions from Malaysian #mangroves #deforestation @bluecology AddThis.

Russian tanker sails through Arctic without icebreaker for first time. World set to use more energy for cooling than heating. The world faces a looming and potentially calamitous “cold crunch”, with demand for air conditioning and refrigeration growing so fast that it threatens to smash pledges and targets for global warming. Worldwide power consumption for air conditioning alone is forecast to surge 33-fold by 2100 as developing world incomes rise and urbanisation advances. Already, the US uses as much electricity to keep buildings cool as the whole of Africa uses on everything; China and India are fast catching up. By mid-century people will use more energy for cooling than heating. And since cold is still overwhelmingly produced by burning fossil fuels, emission targets agreed at next month’s international climate summit in Paris risk being blown away as governments and scientists struggle with a cruel climate-change irony: cooling makes the planet hotter.

Artificial cold is a recent phenomenon: the first domestic air-conditioning unit appeared in 1914, the first home fridges in 1930. But there is a problem.