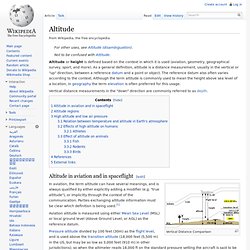

Exosphere. Earth atmosphere diagram showing the exosphere and other layers.

The layers are to scale. From Earth's surface to the top of the stratosphere (50km) is just under 1% of Earth's radius. The exosphere (Ancient Greek: ἔξω éxō "outside, external, beyond", Ancient Greek: σφαῖρα sphaĩra "sphere") is a thin, atmosphere-like volume surrounding a planetary body where molecules are gravitationally bound to that body, but where the density is too low for them to behave as a gas by colliding with each other. Exosphere. High-altitude balloon. High-altitude balloons are unmanned balloons, usually filled with helium or hydrogen, that are released into the stratosphere, generally attaining between 60,000 to 120,000 feet (11 to 23 mi; 18 to 37 km). During 2002, a balloon named BU60-1 attained 53.0 km (32.9 mi; 173,900 ft).[1] The most common type of high altitude balloons are weather balloons. Other purposes include use as a platform for experiments in the upper atmosphere.

Modern balloons generally contain electronic equipment such as radio transmitters, cameras, or satellite navigation systems, such as GPS receivers. These balloons are launched into what is termed "near space"—- the area of Earth's atmosphere where there is very little air, but where the remaining amount generates too much drag for satellites to remain in orbit. Due to the low cost of GPS and communications equipment, high altitude ballooning is a popular hobby, with organizations such as UKHAS assisting the development of payloads.[2][3] History[edit]

Altitude. Vertical distance measurements in the "down" direction are commonly referred to as depth.

Altitude in aviation and in spaceflight[edit] Vertical Distance Comparison In aviation, the term altitude can have several meanings, and is always qualified by either explicitly adding a modifier (e.g. "true altitude"), or implicitly through the context of the communication. Parties exchanging altitude information must be clear which definition is being used.[1] Thermosphere. Earth atmosphere diagram showing the exosphere and other layers.

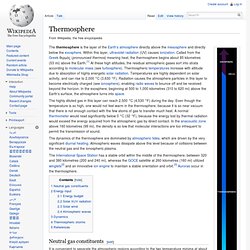

The layers are to scale. From Earth's surface to the top of the stratosphere (50 kilometres (31 mi)) is just under 1% of Earth's radius. Twilight phenomena. A twilight phenomenon (seen from the Louisiana-24 Long Range Tracking Telescope site in northern Santa Barbara county) lights up the night sky over Vandenberg Air Force Base following the launch of a Minuteman III missile September 19, 2002 (Official USAF Photo by Dennis Fisher, 30th Communications Squadron) Twilight phenomenon is produced when unburned particles of missile or rocket propellant and water left in the vapor trail of a launch vehicle condenses, freezes and then expands in the less dense upper atmosphere.

The exhaust plume, which is suspended against a dark sky is then illuminated by reflective high altitude sunlight, which produces a spectacular, colorful effect when seen at ground level. The phenomenon typically occurs with launches that take place either 30 to 60 minutes before sunrise or after sunset when a booster rocket or missile rises out of the darkness and into a sunlit area, relative to an observer's perspective on the ground. Examples[edit] References[edit] Sputnik 1. The signals of Sputnik 1 continued for 22 days.

Sputnik 1 (Russian: "Спу́тник-1" Russian pronunciation: [ˈsputnʲɪk], "Satellite-1", ПС-1 (PS-1, i.e. "Простейший Спутник-1", or Elementary Satellite-1))[2] was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was a 58 cm (23 in) diameter polished metal sphere, with four external radio antennas to broadcast radio pulses. The Soviet Union launched it into an elliptical low Earth orbit on 4 October 1957. It was visible all around the Earth and its radio pulses were detectable. Sputnik itself provided scientists with valuable information.

Space debris. Space debris, also known as orbital debris, space junk and space waste, is the collection of defunct objects in orbit around Earth.

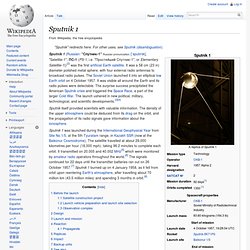

This includes spent rocket stages, old satellites and fragments from disintegration, erosion and collisions. Since orbits overlap with new spacecraft, debris may collide with operational spacecraft. Scientific research on the International Space Station. ESA astronaut Thomas Reiter, STS-116 mission specialist, works with the Passive Observatories for Experimental Microbial Systems in Micro-G (POEMS) payload in the Minus Eighty Degree Laboratory Freezer for ISS (MELFI) inside the Destiny laboratory.

Scientific Research on the International Space Station is a collection of experiments that require one or more of the unusual conditions present in low Earth orbit. The primary fields of research include human research, space medicine, life sciences, physical sciences, astronomy and meteorology.[1][2][3] The 2005 NASA Authorization Act designated the American segment of the International Space Station as a national laboratory with the goal of increasing the use of the ISS by other federal agencies and the private sector.[4] Research on the ISS improves knowledge about the effects of long-term space exposure on the human body.

Subjects currently under study include muscle atrophy, bone loss, and fluid shift. ISS Science Facilities[edit]