Zoom

Trash

Blitz Introduction. Photo 4. Photo 3. Photo 2. Photo 1. Primary History - World War 2 - Scotland's Blitz. World War II (1939-45) - 20th and 21st centuries. The Scots played an important role in the Allied victory - from the battlefields of North Africa to life on the home front.

Clydebank Blitz - World War II (1939-45) On the nights of 13 and 14 March 1941, German bombers attacked the munitions factories and shipyards of Clydeside.

There were 260 bombers on the first night - waves of high-explosive bombs, incendiary bombs and land-mines were dropped over a nine-hour period. Streets were devastated, fires raged, and people were trapped in collapsed buildings. The Polish destroyer ORP Piorun under Commander Eugeniusz Pławski was at John Brown's shipyard undergoing repairs. She joined the defence of Clydebank, firing a tremendous barrage at the Luftwaffe. A memorial to the ship’s crew can be seen in Solidarity Plaza, Clydebank. On 14 March, with rescue work continuing, 200 bombers returned; their bombing raid lasted over seven and a half hours. Evacuation - World War II (1939-45) After war was declared, people expected that the Luftwaffe would bomb Britain and that civilian casualties would be enormous.

The Department of Health in Scotland spent the early months of 1939 preparing details for the evacuation of unaccompanied children, mothers with children under school age, blind people and invalids from vulnerable areas. Areas affected were Edinburgh, Rosyth, Glasgow, Clydebank, Dundee, Inverkeithing and Queensferry – and from May 1941, after the Clydeside air-raids, Greenock, Port Glasgow and Dumbarton were added.

Evacuation was voluntary. Some had made private arrangements but when the order came at 11.07 on 31 August 1939 to ‘Evacuate Forthwith’, nearly 176,000 children assembled; 120,000 leaving Glasgow within three days. Children mustered at their local primary school, carrying their gas-mask, toothbrush, change of underclothes and label. It was a logistical nightmare to process the evacuees on arrival and allocate accommodation. Rationing - World War II (1939-45) After the outbreak of war only essential foods were imported into Britain.

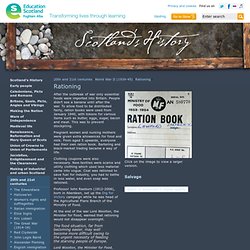

People didn’t see a banana until after the war. To allow food to be distributed fairly, ration books were used from January 1940, with tokens for various items such as butter, eggs, sugar, bacon and meat. This was to prevent stockpiling. Pregnant women and nursing mothers were given extra allowances for food and milk.

From aged 5 upwards, everyone had their own ration book. Clothing coupons were also necessary. Professor John Raeburn (1912-2006), born in Aberdeen, set up the Dig for Victory campaign while he was head of the Agricultural Plans Branch of the Ministry of Food. At the end of the war Lord Woolton, the Minister for Food, warned that rationing would not disappear overnight. The food situation, far from becoming easier, may well become more difficult owing to the urgent necessity of feeding the starving people of Europe.

Dig for Victory - World War II (1939-45) The Dig for Victory campaign encouraged people to transform gardens, parks and sports pitches into allotments to grow vegetables.

People also kept their own chickens, rabbits and goats. Nine hundred pig clubs were set up and about 6000 pigs were raised in gardens. The Government knew the British people could be starved out by a sea blockade; as much imported food came from Canada and America, supplies were vulnerable to attack from the German navy. The British Merchant Navy also had to change its role, to be available for transporting troops and munitions. The Shetland Bus - World War II (1939-45) The Shetland Bus was the name given to the clandestine organisation formed by the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the military intelligence service of Norway’s government-in-exile.

From 1941 till May 1945 the group first used Norwegian fishing boats then later on faster well-armed sub-chasers, based at Scalloway, in Shetland, to ferry agents and equipment into Nazi-occupied Norway and to maintain contact with resistance groups. On return, crews brought out Norwegians who feared arrest by the Germans. Coded messages were passed in BBC broadcasts. Most crossings were made in winter, when daylight was short, with no lights and with North Sea conditions at their worst.

Boats were disguised as working fishing boats with only light machine-guns hidden inside fish-barrels on deck. By the end of the Nazi occupation, the Shetland Bus had taken 192 agents and 383 tons of weapons and supplies to Norway. Around Scotland - World War II. Scotland on Film - Film and Radio Clips.