Polysemy. Charles Fillmore and Beryl Atkins’ definition stipulates three elements: (i) the various senses of a polysemous word have a central origin, (ii) the links between these senses form a network, and (iii) understanding the ‘inner’ one contributes to understanding of the ‘outer’ one.[3] Polysemy is a pivotal concept within disciplines such as media studies and linguistics.

Polysemes[edit] A polyseme is a word or phrase with different, but related senses. Since the test for polysemy is the vague concept of relatedness, judgments of polysemy can be difficult to make. Because applying pre-existing words to new situations is a natural process of language change, looking at words' etymology is helpful in determining polysemy but not the only solution; as words become lost in etymology, what once was a useful distinction of meaning may no longer be so. Examples[edit] Man Mole Bank a financial institutionthe building where a financial institution offers servicesa synonym for 'rely upon' (e.g.

Book Milk. Strange loop. A strange loop arises when, by moving only upwards or downwards through a hierarchical system, one finds oneself back to where one started.

Strange loops may involve self-reference and paradox. Quantum mind–body problem. The von Neumann–Wigner interpretation, also described as "consciousness causes collapse [of the wave function]", is an interpretation of quantum mechanics in which consciousness is postulated to be necessary for the completion of the process of quantum measurement.

Background: Observation in quantum mechanics[edit] In the orthodox Copenhagen interpretation, quantum mechanics predicts only the probabilities for different outcomes of pre-specified observations. What constitutes an "observer" or an "observation" is not directly specified by the theory, and the behavior of a system upon observation is completely different than its usual behavior: The wavefunction that describes a system spreads out into an ever larger superposition of different possible situations. Hard problem of consciousness. The existence of a "hard problem" is controversial and has been disputed by some philosophers.[4][5] Providing an answer to this question could lie in understanding the roles that physical processes play in creating consciousness and the extent to which these processes create our subjective qualities of experience.[3] Several questions about consciousness must be resolved in order to acquire a full understanding of it.

These questions include, but are not limited to, whether being conscious could be wholly described in physical terms, such as the aggregation of neural processes in the brain. If consciousness cannot be explained exclusively by physical events, it must transcend the capabilities of physical systems and require an explanation of nonphysical means. For philosophers who assert that consciousness is nonphysical in nature, there remains a question about what outside of physical theory is required to explain consciousness. Observer effect (physics) In physics, the observer effect is the fact that simply observing a situation or phenomenon necessarily changes that phenomenon.

This is often the result of instruments that, by necessity, alter the state of what they measure in some manner. A commonplace example is checking the pressure in an automobile tire; this is difficult to do without letting out some of the air, thus changing the pressure. Similarly, it is not possible to see any object without light hitting the object, and causing it to emit light. While the effects of observation are often negligible, the object still experiences a change. This effect can be observed in many domains of physics and can often be reduced to insignificance by using different instruments or observation techniques. Chinese room. The Chinese room is a thought experiment presented by John Searle to challenge the claim that it is possible for a digital computer running a program to have a "mind" and "consciousness" in the same sense that people do, simply by virtue of running the right program.

According to Searle, when referring to a hypothetical computer program which can be told a story then answer questions about it: Partisans of strong AI claim that in this question and answer sequence the machine is not only simulating a human ability but also (1) that the machine can literally be said to understand the story and provide the answers to questions, and (2) that what the machine and its program do explains the human ability to understand the story and answer questions about it.

To contest this view, Searle writes in his first description of the argument: "Suppose that I'm locked in a room and ... that I know no Chinese, either written or spoken". Chinese room thought experiment[edit] More general context[edit] Intuition pump. In the case of the Chinese Room argument, Dennett argues that the intuitive notion that a person manipulating symbols seems inadequate to constitute any form of consciousness ignores the requirements of memory, recall, emotion, world knowledge and rationality that the system would actually need to pass such a test.

"Searle does not deny that programs can have all this structure, of course," Dennett says.[2] "He simply discourages us from attending to it. But if we are to do a good job imagining the case, we are not only entitled but obliged to imagine that the program Searle is hand-simulating has all this structure — and more, if only we can imagine it. But then it is no longer obvious, I trust, that there is no genuine understanding of the joke going on.

" A popular strategy in philosophy is to construct a certain sort of thought experiment I call an intuition pump [...]. See also[edit] References[edit] Jump up ^ Baggini, Julian; Peter Fosl (2003). "2". External links[edit] Twin Earth thought experiment. The Twin Earth thought experiment was a thought experiment presented by philosopher Hilary Putnam in his 1973 paper "Meaning and Reference" and subsequent 1975 paper "The Meaning of 'Meaning'", as an early argument for what has subsequently come to be known as semantic externalism.

Swampman. Suppose Davidson goes hiking in the swamp and is struck and killed by a lightning bolt.

At the same time, nearby in the swamp another lightning bolt spontaneously rearranges a bunch of molecules such that, entirely by coincidence, they take on exactly the same form that Davidson's body had at the moment of his untimely death.This being, whom Davidson terms "Swampman," has, of course, a brain which is structurally identical to that which Davidson had, and will thus, presumably, behave exactly as Davidson would have. He will walk out of the swamp, return to Davidson's office at Berkeley, and write the same essays he would have written; he will interact like an amicable person with all of Davidson's friends and family, and so forth. Davidson holds that there would nevertheless be a difference, though no one would notice it. Swampman will appear to recognize Davidson's friends, but it is impossible for him to actually recognize them, as he has never seen them before. Philosophy of mind.

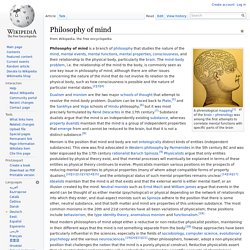

A phrenological mapping[1] of the brain – phrenology was among the first attempts to correlate mental functions with specific parts of the brain Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the nature of the mind, mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness, and their relationship to the physical body, particularly the brain.

The mind–body problem, i.e. the relationship of the mind to the body, is commonly seen as one key issue in philosophy of mind, although there are other issues concerning the nature of the mind that do not involve its relation to the physical body, such as how consciousness is possible and the nature of particular mental states.[2][3][4] Mind–body problem[edit] Our perceptual experiences depend on stimuli that arrive at our various sensory organs from the external world, and these stimuli cause changes in our mental states, ultimately causing us to feel a sensation, which may be pleasant or unpleasant. Arguments for dualism[edit] Neuroscience of free will.

Neuroscience of free will is the part of neurophilosophy that studies the interconnections between free will and neuroscience. As it has become possible to study the living brain, researchers have begun to watch decision making processes at work. Findings could carry implications for our sense of agency and for moral responsibility and the role of consciousness in general.[1][2][3] Relevant findings include the pioneering study by Benjamin Libet and its subsequent redesigns; these studies were able to detect activity related to a decision to move, and the activity appears to begin briefly before people become conscious of it.[4] Other studies try to predict activity before overt action occurs.[5] Taken together, these various findings show that at least some actions - like moving a finger - are initiated unconsciously at first, and enter consciousness afterward.[6] A monk meditates.

Overview[edit] -Patrick Haggard[6] discussing an in-depth experiment by Itzhak Fried[13] Consciousness. Representation of consciousness from the seventeenth century At one time consciousness was viewed with skepticism by many scientists, but in recent years it has become a significant topic of research in psychology, neuropsychology and neuroscience. The primary focus is on understanding what it means biologically and psychologically for information to be present in consciousness—that is, on determining the neural and psychological correlates of consciousness. The majority of experimental studies assess consciousness by asking human subjects for a verbal report of their experiences (e.g., "tell me if you notice anything when I do this"). Issues of interest include phenomena such as subliminal perception, blindsight, denial of impairment, and altered states of consciousness produced by drugs and alcohol, or spiritual or meditative techniques.

Etymology and early history[edit]