Digital. Historical. People. New Herbaria. Africa. Asia. Britain + Europe. Middle East. South America. US. Research output of herbaria. Collections Lens. YES completely agree. However, I am still struck when I first came to collections to find there are basically no rules, no real standardization. Even in very detailed labels, one person’s “associated species” “habitat” etc is not another’s. Useful, but no.

Herbaria, Seeds Banks and Fungaria - BOTANICAL ART & ARTISTS. Www.pitchandikulam-herbarium.org. BSBI Cymru. Not just a collection of old dead leaves! – The Old Man of Wytham. In my teenage years, I squashed plants and sellotaped them into to a far-too-small notebook.

The World’s Herbaria 2017 5 Jan 2018. Index Herbariorum Annual Report - The William & Lynda Steere Herbarium. The Changing Role of Herbaria in the Twenty-first Century and a Case Study of the University of California Los Angeles Herbarium. The power of herbaria: a time machine for plant biology research - Mapping Ignorance. Naturalists and scientists have been collecting plants or plant parts during centuries to make collections and catalogues known as herbaria (sing. herbarium) that have been traditionally used for comparative taxonomy and systematics research.

We have a new exhibition installed showing what goes on inside the herbarium #DBNherbarium. Great work by everyone to get this done in the short timeframe. Still a few tweaks needed. @NBGGlasnevin Now we have the small matter of detailing all our collecti. Herbarium: Functions, Kinds and Importance. Feel like doing a craft activity this #BankHolidayWeekend? Why not bring nature indoors and try your hand at flower pressing? Discover how to press flowers: □ □ The Herbarium. The Herbarium explained The Herbarium is a collection of preserved plants that are stored, catalogued, and arranged systematically for study.

When specimens are collected in the field, the Herbarium and associated information in the library is used to identify these specimens, to determine how one species differs from another, or whether a specimen represents a species new to science. Herbarium specimens act as a source of information, to determine: what the plants look like; where they are found; what environmental niche they occupy; which species are threatened by extinction; what morphological and chemical variation occurs; and, when they flower or produce seed. Specimens can be used to provide samples of DNA to study relationships and evolutionary processes. They also act as vouchers to validate scientific observations. @KeeperNH browsing the collections in the Herbarium in Focus. Until 1970 these plant and museum collections were in the Natural History Museum @NMIreland @opwireland.

Coworkers made some sweet button giveaways. #herbarium peeps, PLEASE STEAL THIS IDEA. A great use for small loose homeless fragments! Credit to SABS/Castanea for the original “Botany Y’all” idea. Bracken. Bracken Posted on August 6, 2019 Updated on August 7, 2019 A Memoir by Daniel Quall King.

Kew Gardens LAA Team sur Twitter : "Queen Charlotte, wife to George III, died in the Gardens in Kew Palace on 17th November 1818. Charlotte had a keen interest in botany; keeping herbarium specimens and taking tuition in flower painting from Margaret Meen. The Herbarium: An Interior Landscape of Science. Editor’s note: This is the fifth in a series of posts considering the intersection between environmental history and the histories of science, technology and medicine.

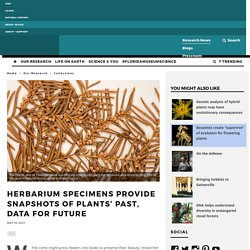

Previous posts can be found here. A plaque describing the Economic Botany Collection at Kew. Author’s photograph. Botany is a science of many places. Manchester Herbarium. Herbarium specimens provide snapshots of plants’ past, data for future – #FloridaMuseumScience. While some might press flowers into books to preserve their beauty, researcher Mark Whitten does it to preserve history.

Narratives of the Herbarium of RBGE. Background to the project.

The advent of the era of Big Data has highlighted a truism in scientific discovery: an inference is only as good as the data that underlie it. While it is tempting to believe that large, open-access data repositories are a recent invention, in fact scientific collections such as herbaria have been filling this purpose for hundreds of years. But, while the data in these collections are nearly always open (e.g., the Royal Botanic Garden Herbarium has shared specimens with any who so request since at least the 1960s), they are not always accessible.

From Joseph Banks to big data, herbaria bring centuries-old science into the digital age. Last month, priceless botanical specimens were destroyed after an apparent miscommunication between scientists and Australian customs officials.

Although unfortunate, the incident has focused attention on the importance of being able to share scientific specimens around the world, and the vital role that herbaria play in modern science. Despite being sometimes described as “museums for plants”, herbaria aren’t just natural history storage and displays. In this era of DNA barcoding, big data, biosecurity threats, bio-prospecting, and global information sharing, herbaria are complex and evolving institutions.

The modern herbarium is steeped in tradition and full of antiquities, but it also leads the application of modern approaches to understanding our past, present and future natural world. The power of 8 million specimens. Botany is not dead, but this plant is. Jennifer Ackerfield, Herbarium Curator in the Biology Department, shows off specimens in the CSU collection.

May 12, 2015. Image via J. Ackerfield. Guest post from Colorado State University Herbarium Collections Manager Jennifer Ackerfield. She literally wrote the book on Colorado flora. Preserving plants for the future. Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium: A Forgotten Treasure at the Intersection of Science and Poetry. In an era when the scientific establishment barred and bolted its gates to women, botany allowed Victorian women to enter science through the permissible backdoor of art, most famously in Beatrix Potter’s scientific drawings of mushrooms and Margaret Gatty’s stunning illustrated classification of seaweed. Across the Atlantic, this art-science adventure in botany found an improbable yet impassioned practitioner in one of humanity’s most beloved and influential poets: Emily Dickinson (December 10, 1830–May 15, 1886). Long before she began writing poems, Dickinson undertook a rather different yet unexpectedly parallel art of contemplation and composition — the gathering, growing, classification, and pressing of flowers, which she saw as manifestations of the Muse not that dissimilar to poems.

Emily Dickinson. The Worlds Herbaria 2018. Herbarium.