Frontier of Physics: Interactive Map. “Ever since the dawn of civilization,” Stephen Hawking wrote in his international bestseller A Brief History of Time, “people have not been content to see events as unconnected and inexplicable.

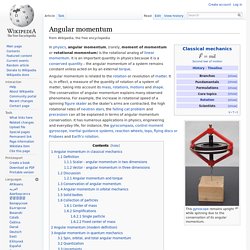

They have craved an understanding of the underlying order in the world.” In the quest for a unified, coherent description of all of nature — a “theory of everything” — physicists have unearthed the taproots linking ever more disparate phenomena. With the law of universal gravitation, Isaac Newton wedded the fall of an apple to the orbits of the planets. Albert Einstein, in his theory of relativity, wove space and time into a single fabric, and showed how apples and planets fall along the fabric’s curves. And today, all known elementary particles plug neatly into a mathematical structure called the Standard Model. Our map of the frontier of fundamental physics, built by the interactive developer Emily Fuhrman, weights questions roughly according to their importance in advancing the field. Vector Model of Angular Momentum. Once you have combined orbital and spin angular momenta according to the vector model, the resulting total angular momentum can be visuallized as precessing about any externally applied magnetic field.

This is a useful model for dealing with interactions such as the Zeeman effect in sodium. The magnetic energy contribution is proportional to the component of total angular momentum along the direction of the magnetic field, which is usually defined as the z-direction. The z-component of angular momentum is quantized in values one unit apart, so for the upper level of the sodium doublet with j=3/2, the vector model gives the splitting shown. Even with the vector model, the determination of the magnitude of the Zeeman spliting is not trivial since the directions of S and L ar constantly changing as they precess about J. This problem is handled with the Lande' g-factor.

Quantized Angular Momentum. Lagrangian formalism - Intuition Behind Conservation of Angular Momentum. Threshold size for quantum effects. Angular Momentum. Angular momentum. This gyroscope remains upright while spinning due to the conservation of its angular momentum.

In physics, angular momentum, (rarely, moment of momentum or rotational momentum) is the rotational analog of linear momentum. It is an important quantity in physics because it is a conserved quantity – the angular momentum of a system remains constant unless acted on by an external torque. Angular momentum in classical mechanics[edit] Definition[edit] First principle. A first principle is a basic proposition or assumption that cannot be deduced from any other proposition or assumption.

In philosophy, first principles are from First Cause[1] attitudes and taught by Aristotelians, and nuanced versions of first principles are referred to as postulates by Kantians.[2] In mathematics, first principles are referred to as axioms or postulates. In physics and other sciences, theoretical work is said to be from first principles, or ab initio, if it starts directly at the level of established science and does not make assumptions such as empirical model and parameter fitting.

In formal logic[edit] In a formal logical system, that is, a set of propositions that are consistent with one another, it is possible that some of the statements can be deduced from other statements. For example, in the syllogism, "All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; Socrates is mortal" the last claim can be deduced from the first two. Philosophy in general[edit] Terence Irwin writes:

Particle and nuclear physics. Advanced mathematical methods. Quantum physics. Pràctiques externes. Thermodynamics and statistical mechanics. Optics. Numerical methods. Symmetries, conservation laws and Noether's Theorem. Electro. Chemistry. Differential equations. Mechanics LAB. Classical Mechanics. Multivariable Calculus. The Speed Of Light Can Vary In A Vacuum.

Quantum physics just got less complicated. Here's a nice surprise: quantum physics is less complicated than we thought.

An international team of researchers has proved that two peculiar features of the quantum world previously considered distinct are different manifestations of the same thing. The result is published 19 December in Nature Communications. Patrick Coles, Jedrzej Kaniewski, and Stephanie Wehner made the breakthrough while at the Centre for Quantum Technologies at the National University of Singapore. They found that 'wave-particle duality' is simply the quantum 'uncertainty principle' in disguise, reducing two mysteries to one. "The connection between uncertainty and wave-particle duality comes out very naturally when you consider them as questions about what information you can gain about a system.

The discovery deepens our understanding of quantum physics and could prompt ideas for new applications of wave-particle duality. Explore further: A new 'lens' for looking at quantum behavior. Gauge esto, Gauge lo otro… ¿Qué es una teoría gauge? La palabra gauge la encontramos por doquier en los escritos sobre física.

Aparecen expresiones como simetría gauge, invariancia gauge, bosones gauge, teorías gauge, etc. Sin embargo, pocas veces se explica con propiedad qué es esta teoría, por qué es tan fundamental y cómo la entienden y por qué la veneran tanto los físicos. ¿Por qué La Tierra está achatada por los polos? La densidad de La Tierra. En su elaboración de la Teoría de Gravitación Universal, Newton ya se dio cuenta de que en La Tierra, a consecuencia de su movimiento de rotación y según su Ley de atracción, cada partícula de masa m a diferente distancia del eje, estaría expuesta a una diferente Fuerza Centrípeta, ya que describe un movimiento circular uniforme de diferente radio alrededor del eje de rotación de La Tierra.

Según la segunda ley de Newton, para que se produzca una aceleración debe actuar una fuerza en la dirección de esa aceleración. Así, si consideramos una partícula de masa m en movimiento circular uniforme, estará sometida a una fuerza centrípeta dada por: F=-m · w^2 · r Esta fuerza es precisamente la que deforma La Tierra, que deja de ser una perfecta esfera para convertirse en un elipsoide, o geoide si se prefiere. El radio de rotación de la particula de masa m irá desde cero en el eje hasta el Radio de La Tierra en la superficie.