Female Artists Archives - How To Talk About Art History. Tonight, I co-hosted the Bangkok edition of the global ‘Art + Feminism’ Wikipedia campaign.

Nine people total came together in a Bangkok café to learn about Wikipedia, to find out about art and to add/edit/translate articles about woman-identified artists to improve coverage of women-identified artists across the world. At the end of the night, these were our accomplishments: Over the next few months, I will be creating Artist Features about each of these artists on this blog. Thank you to everyone who participated, and to everyone who will continue researching, writing and learning about women-identified artists! "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?": A Case Study - How To Talk About Art History. This post is a collaboration with Jennifer Dasal from the ArtCurious Podcast, in which we’ve both taken art historian Linda Nochlin’s 1971 article, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”

And talked about it from new, contemporary perspectives. 11 Contemporary, Famous Female Painters: Modern Women Artists. When you think of contemporary painters who made an impact on the world who comes to mind?

You might think of Andy Warhol and his famous Campbell’s Soup cans or maybe Roy Lichtenstein and his comic book-inspired paintings. What you may not realize is how many female painters have made, and are currently making, just as much of an impact.

How our art museums finally opened their eyes to Australian women artists. This is an edited extract from the new book Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening Our Eyes published by Thames & Hudson.

It is a longer read, at just over 3000 words. The 1970s saw major changes in the status of women, which led to more women artists being included in exhibitions, as well as art histories conceived from a feminist perspective. Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch was published in the UK in 1970. Although she visited Australia to promote its publication in 1972, it took some time for those running arts organisations to notice the arrival of second-wave feminism. Women and Power: A walk through Tate Britain – In the Gallery. Over 100 years have passed since the Representation of the People Act of 1918 gave some women in Britain the right to vote.

Inspired by this landmark moment in the journey towards female equality, our online tour looks at some of the artists who have resisted traditional expectations of what women can and should do. The following artworks can be seen for free as part of the Walk Through British Art display at Tate Britain. Mary Beale Mary Beale is often credited as Britain’s first professional female artist. Unusually for the time, she was the breadwinner of her family. She was seen as an authoritative figure on art and respected by many of her male peers. We know a lot about her life and paintings through the notebooks of her husband Charles. Friends and family members were the most common subjects for her paintings.

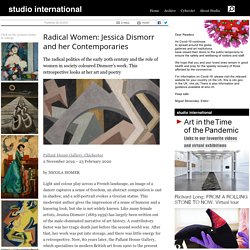

Find out more about the 1650 gallery Emily Mary Osborn Nameless and Friendless is as bleak a painting as its title suggests. Radical Women: Jessica Dismorr and her Contemporaries. Pallant House Gallery, Chichester 2 November 2019 – 23 February 2020 by NICOLA HOMER Light and colour play across a French landscape, an image of a dancer captures a sense of freedom, an abstract composition is cast in shadow, and a self-portrait evokes a Grecian statue.

This modernist author gives the impression of a sense of humour and a knowing look, but she is not widely known. Like many female artists, Jessica Dismorr (1885-1939) has largely been written out of the male-dominated narrative of art history. A contributory factor was her tragic death just before the second world war. Jessica Dismorr. While sisterhood is part of the exhibition, which explores the friendships among the artist and her contemporaries, such as Helen Saunders, the guiding spine is the presence of Dismorr. Jessica Dismorr. Helen Saunders. Paula Rego – interview: ‘I’m interested in seeing things from the underdog’s perspective. Usually that’s a female perspective’ By JULIET RIX Paula Rego is not necessarily thought of as a political artist.

With so much of her work drawing on stories – folk tales, myth and characters from literature (sometimes in surreal combinations) – her reputation is more for subverted narrative than protest. But her art has been political from the start. Born in Lisbon in 1935, Rego grew up under the fascist dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar. Her father secretly printed anti-government leaflets, and paintings such as Salazar Vomiting the Homeland (1960) made Rego’s own views on the subject riskily clear. Paula Rego, Salazar Vomiting The Homeland, 1960. Artists by art movement: Feminist Art. A Brief History of Women in Art (article) Female artists ♀ Feminist Artists. Guerrilla Girls: 'You have to question what you see' – Interview. Nasty Women of History and Art - New York City Art Museum Tours.

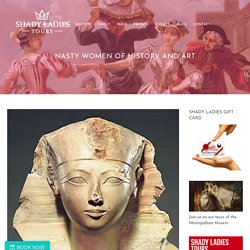

21 Jan Nasty Women of History and Art It seems unbelievably dated, but people are still calling ambitious, intelligent women “nasty women.”

As if that could hurt anyone’s feelings in 2020! In fact, like many other outdated insults, it has the opposite effect. Many women today are are taking the term on (as lesbians took on the term ‘dyke’) and calling themselves “nasty women” in sarcastic protest. In this spirit, I would like to offer up a few women who were “nasty women” in the past, but nasty only in this sense. Ancient Queens To show that there have *always* been ambitious, “nasty women,” let’s start in the distant past, with a female Pharaoh, Hatshepsut, who ruled over Egypt from 1478 to 1458 BC. “Nanette,” Reviewed: Hannah Gadsby’s Netflix Standup Special Forces Comedy to Confront the #MeToo Era. “What sort of comedian can’t even make the lesbians laugh?”

The Australian comedian Hannah Gadsby asks in her new Netflix standup special, “Nanette.” “Every comedian ever,” she answers, grinning conspiratorially, her eyebrows darting behind horn-rim glasses. “The only people who don’t think it’s funny are us lezzes, but we’ve gotta laugh, because if we don’t—proves the point!” It’s a good joke, knowing and playful in the style that Gadsby, a star in her home country, has built her comedy career on.

But it also contains a seed of discomfort: the image of the hypothetical gay woman in the audience, not quite comfortable with the joke, but being conscripted into laughing anyway, at her own expense. This gesture is intentional.