Fashion turns to technology to tailor sustainable solutions. Paris, France – Highlighting the growth of fast fashion – at least in the form of increasing volumes of cheap and disposable clothing – TRAID’s warehouse in London was receiving around 3,000 tonnes of donated clothes every year before coronavirus hit.

“We’re sorting through more volume and finding less that can go into our shops than a few years ago,” said Leigh McAlea, head of communications at TRAID, the United Kingdom-based clothes charity that aims to reduce the environmental and social impact of the fashion industry by encouraging people to shop second-hand. “We’re seeing a lot of fast fashion items, a lot of clothes that have been barely worn or still have tags on.

Items that go into our 12 charity shops have to be good enough quality to resell, whether they’re Primark or Prada. We want to encourage people to buy better quality and then donate items when they have finished with them,” McAlea told Al Jazeera. Green is the new black. Is fast fashion giving way to the sustainable wardrobe? Fashion shoppers spent about £3.5bn on Christmas party clothing this year – but 8 million of those sparkly items will be on their way to landfill after just one wear.

So-called fast fashion has ushered throwaway culture into the clothing business, with items so cheap they have become single-use purchases. Last week, the young-fashion brand Boohoo had 486 dresses available online for less than £5. Many – like a black bandeau jersey bodycon number – were just £3.75, meaning the delivery charge cost more than the contents of the package.

Rival Asos was offering 257 dresses and 2,141 different tops for less than £10. Now, however, some fashion experts believe the party could be coming to an end for such disposable clothing and a backlash could be brewing, just as it has against takeaway coffee cups, plastic packaging and meat. In the past 15 years, global clothing production has doubled to meet demand. “We have only got 12 years to tackle damaging climate change,” she says. Fashion Nova, H&M, Zara: Why we can’t stop buying fast fashion. If you’ve bought clothes in the past decade, odds are that at least one item came from a fast fashion brand.

Stores like Zara and H&M, two of the largest retailers in the world, still hold a stronghold over most people’s shopping habits, even with the rise of online shopping brands. These big, brightly lit stores seemed to pop up in malls overnight sometime in the late 2000s, carrying everything from skinny jeans to work blouses to cocktail dresses, often for significantly less money than stores like Gap or Nordstrom. Still, these shopping behemoths aren’t without controversy. Their speedy supply chains rely on outsourced and often underpaid labor from factory workers overseas. The process is also environmentally damaging and resource-intensive, and to top it off, it’s hard to definitively quantify the industry’s impact. Meanwhile, most people aren’t always aware of fast fashion’s ongoing problems until a big news story breaks.

The Unsustainable Growth of Fast Fashion – Think Sustainability. Each year, more than 100 billion garments are made and around $450 billion worth of textiles are thrown away around the world.

With the emergence of fast fashion, that figure is set to rise in the coming years to unimaginable levels. As with almost all industries around the world, the fashion industry has transitioned from an economy that was once circular, meaning there was no waste produced, to a more linear model where only 1% of textile waste is currently being recycled into new clothing. So how did an industry that was once so almost completely circular end up as one of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases and producers of waste, and how is fast fashion going to compound these problems in the future? Integrating Fashion into the ‘Throwaway Society’ The ‘throwaway society’ we live in today started during the Industrial Revolution. Can The High Street Ever Be Sustainable? My shopping habits have been known to look something like this: 1.

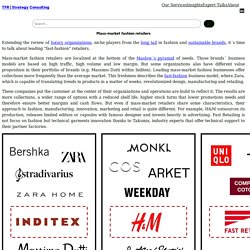

Spot an influencer I follow on Instagram wearing the high street’s latest cult dress. 2. Swipe. Click. Buy. 3. 12 hours later I’m wearing it, maybe even posting about it (if I love it enough). Mass-market fashion retailers – The Fashion Retailer. Extending the review of luxury organizations, niche players from the long tail in fashion and sustainable brands, it´s time to talk about leading “fast-fashion” retailers.

Mass-market fashion retailers are localized at the bottom of the Maslow´s pyramid of needs. Those brands´ business models are based on high traffic, high volume and low margin. But some organizations also have different value proposition in their portfolio of brands (e.g. Massimo Dutti within Inditex). Leading mass-market fashion businesses offer collections more frequently than the average market. These companies put the customer at the center of their organizations and operations are build to reflect it.

Fashionmarketinglessons. What Is Fast Fashion? - Good On You. Clothes shopping used to be an occasional event—something that happened a few times a year when the seasons changed, or when we outgrew what we had.

But about 20 years ago, something changed. Clothes became cheaper, trend cycles sped up, and shopping became a hobby. Fashion History Lesson: The Origins of Fast Fashion. Welcome to our new column, Fashion History Lesson, in which we dive deep into the origin and evolution of the fashion industry's most influential and omnipresent businesses, icons, products and more.

A Five-Minute History of Fast Fashion in the UK. When you think of the phrase "fast fashion", you likely envisage something pretty specific: quickly-made clothes catering to micro-trends (currently: massive puffy sleeves and excessive ruched sateen), sold at a low price point by retailers like Boohoo, Pretty Little Thing, ASOS and In The Style.

These clothes are frequently advertised by Instagram influencers (though there are now more TV ads being placed during shows like Love Island and Ibiza Weekender, aimed at capturing the shared target demographic of young women), and, importantly, the companies selling them overwhelmingly operate online. As a result of their popularity, more and more clothes are being purchased through the internet: in 2018, 24 percent of all apparel sales in the UK were online, up twofold from 12.2 percent in 2015.

A closer look at the history of the high street shows that, in many ways, we've been building towards the desperately wasteful status quo for the last 200 years. @hiyalauren.