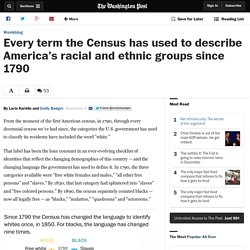

Measuring Race and Ethnicity Across The Decades: 1790—2010. Every term the Census has used to describe America’s racial and ethnic groups since 1790. From the moment of the first American census, in 1790, through every decennial census we've had since, the categories the U.S. government has used to classify its residents have included the word "white.

" That label has been the lone constant in an ever-evolving checklist of identities that reflect the changing demographics of this country — and the changing language the government has used to define it. In 1790, the three categories available were "free white females and males," "all other free persons" and "slaves. " By 1830, that last category had splintered into "slaves" and "free colored persons. " By 1890, the census separately counted blacks — now all legally free — as "blacks," "mulattos," "quadroons" and "octoroons. " These changes, the Census Bureau points out, have been driven by cultural and economic shifts, by events like emancipation, immigration and the civil rights movement. Voices: 'Aliens?' Not Our Friends and Neighbors. When I found out Rep.

Joaquín Castro, D-San Antonio, proposed that the federal government replace the word 'alien' and 'illegal alien' in its laws and official documents with the term 'foreign national' and 'undocumented foreign national' I let out an emphatic and primal 'Yaaasssss!!!!! ' Not because passage of his proposal is likely, but because there was somebody in the halls of Congress that would think to propose this overdue idea at all.

I'm not a fan of political correctness. It's usually license for terrible behavior and doesn't push the conversation forward. I am, however, a fan of political truth and the truth is words matter. RELATED: Rep. The Persuasive Power of Repeated Falsehoods. Chances are you heard some blatantly untrue statements during last night's debate.

It's a cynical, manipulative strategy, but it works: Psychological studies have consistently shown that oft-repeated statements are more likely to be perceived as true, regardless of their actual veracity. Since this "Illusory Truth Effect" was first noted in the late 1970s, it has been widely assumed that this ploy is effective only on people unfamiliar with the issue in question. Knowledge of the subject matter will lead people to dismiss the lie and distrust the liar, one might assume. But a newly published study reports that's not necessarily true: Even those of us with a solid grasp of the issue at hand are susceptible to this sort of misinformation. The Iron Cage in Binary Code: How Facebook Shapes Your Life Chances. By Tressie McMillan Cottom, 1 day ago at 08:44 am There was a great article in The Nation last week about social media and ad hoc credit scoring.

Can Facebook assign you a score you don’t know about but that determines your life chances? Traditional credit scores like your FICO or your Beacon score can determine your life chances. By life chances, we generally mean how much mobility you will have. Here, we mean a number created by third party companies often determines you can buy a house/car, how much house/car you can buy, how expensive buying a house/car will be for you. It does not seem like Facebook is issuing a score, or a number, of your creditworthiness per se. One of the authors of The Nation piece (disclosure: a friend), Astra Taylor, points out how her Facebook ads changed when she started using Facebook to communicate with student protestors from for-profit colleges.

You get ads like this one from DeVry: It is in interesting twist on how credit scoring shapes life chances. How Our Brains Perceive Race. This post first appeared at Mother Jones.

Hiphop dance troupe at Pacific Northwest Black Community Festival, Seattle, 2010. (Photo: Joe Mabel/flickr CC 2.0) “You’re not, like, a total racist bastard,” David Amodio tells me. 22 Maps That Show The Deepest Linguistic Conflicts In America. Is the Sky Blue? For the last week of December, we’re re-posting some of our favorite posts from 2012.

A recent episode of Radiolab centered on questions about colors. It profiled a British man who, in the 1800s, noticed that neither The Odyssey nor The Iliad included any references to the color blue. In fact, it turns out that, as languages evolve words for color, blue is always last. Red is always first. This is the case in every language ever studied. Scholars theorize that this is because red is very common in nature, but blue is extremely rare. An exception to the rarity of blue in nature, of course — one that might undermine this theory — is the sky. Well, it turns out that seeing blue when we look up is dependent on already knowing that the sky is blue. But Deutscher and his wife avoided ever telling Alma that the sky was blue. Alma, at first, was puzzled. Deutscher kept asking on “sky blue” days and one day she answered: the sky was white.