Strawinsky: Le chant du rossignol ∙ hr-Sinfonieorchester ∙ Juraj Valčuha. Democritus. Democritus (; Greek: Δημόκριτος, Dēmókritos, meaning "chosen of the people"; c. 460 – c. 370 BC) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe.[3] Democritus was born in Abdera, Thrace,[4] around 460 BC, although there are disagreements about the exact year.

His exact contributions are difficult to disentangle from those of his mentor Leucippus, as they are often mentioned together in texts. Their speculation on atoms, taken from Leucippus, bears a passing and partial resemblance to the 19th-century understanding of atomic structure that has led some to regard Democritus as more of a scientist than other Greek philosophers; however, their ideas rested on very different bases.[5] Largely ignored in ancient Athens, Democritus is said to have been disliked so much by Plato that the latter wished all of his books burned.[6] He was nevertheless well known to his fellow northern-born philosopher Aristotle. Leucippus. Leucippus (; Greek: Λεύκιππος, Leúkippos; fl. 5th cent.

BCE) is reported in some ancient sources to have been a philosopher who was the earliest Greek to develop the theory of atomism—the idea that everything is composed entirely of various imperishable, indivisible elements called atoms. Leucippus often appears as the master to his pupil Democritus, a philosopher also touted as the originator of the atomic theory. "Aristotle and Theophrastos certainly made him [Leucippus] the originator of the atomic theory, and they can hardly have been mistaken on such a point. Hesiod. Ancient Greek poet Hesiod (;[1] Greek: Ἡσίοδος Hēsíodos, 'he who emits the voice') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.[2][3] He is generally regarded as the first written poet in the Western tradition to regard himself as an individual persona with an active role to play in his subject.[4] Ancient authors credited Hesiod and Homer with establishing Greek religious customs.[5] Modern scholars refer to him as a major source on Greek mythology, farming techniques, early economic thought,[6] archaic Greek astronomy and ancient time-keeping.

Life[edit] Hesiod and the Muse (1891), by Gustave Moreau. Occam's razor. Philosophical principle of selecting the solution with the fewest assumptions Occam's razor, Ockham's razor, Ocham's razor (Latin: novacula Occami) or law of parsimony (Latin: lex parsimoniae) is the problem-solving principle that "entities should not be multiplied without necessity"[1][2] or, more simply, the simplest explanation is usually the right one.

The idea is attributed to English Franciscan friar William of Ockham (c. 1287–1347), a scholastic philosopher and theologian who used a preference for simplicity to defend the idea of divine miracles. This philosophical razor advocates that when presented with competing hypotheses about the same prediction, one should select the solution with the fewest assumptions,[3] and that this is not meant to be a way of choosing between hypotheses that make different predictions. William of Ockham. Franciscan friar and theologian in medieval England Sketch labelled "frater Occham iste", from a manuscript of Ockham's Summa Logicae, 1341 William of Ockham (; also Occam, from Latin: Gulielmus Occamus;[9][10] c. 1287 – 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, and theologian, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey.[11] He is considered to be one of the major figures of medieval thought and was at the centre of the major intellectual and political controversies of the 14th century.

He is commonly known for Occam's razor, the methodological principle that bears his name, and also produced significant works on logic, physics, and theology. Potentiality and actuality. Teleology. A teleology (from Ancient Greek telos, meaning roughly "end" or "purpose",[1] and -logia, meaning "study of, discourse") is an account of a given thing's end or purpose.

For instance, we might give a teleological account of why forks have prongs by showing their purpose—how the design helps humans to eat certain foods. Stabbing food and helping humans eat is what forks are for. There are two kinds of telos or end. The purpose or telos of a fork is extrinsic or imposed on it by the user.[2] The notion of natural teleology is that natural entities have intrinsic teloi or ends, irrespective of human use or opinion. For instance, Aristotle held that an acorn's intrinsic telos is to become a fully grown oak tree.[3] Though ancient atomists rejected the notion of natural teleology, teleological accounts of non-personal or non-human nature were explored and often endorsed in ancient and medieval philosophies, but fell into disfavor during the modern era (1600-1900).

Physis. Four causes. Aristotle's Four Causes illustrated for a table: material (wood), formal (design), efficient (carpentry), final (dining).

The four causes are elements of an influential principle in Aristotelian thought whereby explanations of change or movement are classified into four fundamental types of answer to the question "why? ". Aristotle wrote that "we do not have knowledge of a thing until we have grasped its why, that is to say, its cause. "[1][2] While there are cases in which classifying a "cause" is difficult, or in which "causes" might merge, Aristotle held that his four "causes" provided an analytical scheme of general applicability.[3] Unmoved mover. First philosophy[edit] Celestial spheres[edit] Final cause and efficient cause[edit] Simplicius argues that the first unmoved mover is a cause not only in the sense of being a final cause—which everyone in his day, as in ours, would accept—but also in the sense of being an efficient cause (1360. 24ff.), and his master Ammonius wrote a whole book defending the thesis (ibid. 1363. 8-10).

Simplicius's arguments include citations of Plato's views in the Timaeus—evidence not relevant to the debate unless one happens to believe in the essential harmony of Plato and Aristotle—and inferences from approving remarks which Aristotle makes about the role of Nous in Anaxagoras, which require a good deal of reading between the lines. But he does point out rightly that the unmoved mover fits the definition of an efficient cause—'whence the first source of change or rest' (Phys. Troglodytae. Legendary tribe of African nomads in Greco-Roman historiography The Troglodytae (Greek: Τρωγλοδύται), or Troglodyti (literally "cave goers"), were a people mentioned in various locations by many ancient Greek and Roman geographers and historians, including Herodotus (5th century BCE), Agatharchides (2nd century BCE), Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE), Strabo (64/63 BCE – c. 24 CE), Pliny (1st century CE), Josephus (37 – c. 100 CE), and Tacitus (c. 56 – after 117 CE).

Greco-Roman period[edit] The earlier references allude to Trogodytes (without the l), evidently derived from Greek trōglē, cave and dytes, divers.[1] Allegory of the Cave. Allegory by Plato Plato has Socrates describe a group of people who have lived chained to the wall of a cave all of their lives, facing a blank wall.

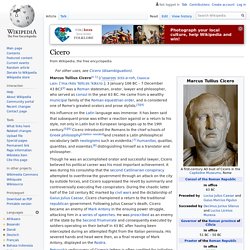

The people watch shadows projected on the wall from objects passing in front of a fire behind them, and give names to these shadows. Cicero. 1st-century BC Roman lawyer, orator, philosopher and statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero[n 1] ( SISS-ə-roh, Classical Latin: [ˈmaːrkʊs ˈtʊllɪ.ʊs ˈkɪkɛroː]; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC)[2] was a Roman statesman, orator, lawyer and philosopher, who served as consul in the year 63 BC.

He came from a wealthy municipal family of the Roman equestrian order, and is considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.[3][4] His influence on the Latin language was immense: it has been said that subsequent prose was either a reaction against or a return to his style, not only in Latin but in European languages up to the 19th century.[5][6] Cicero introduced the Romans to the chief schools of Greek philosophy[citation needed]and created a Latin philosophical vocabulary (with neologisms such as evidentia,[7] humanitas, qualitas, quantitas, and essentia),[8] distinguishing himself as a translator and philosopher. Teleological argument. The teleological or physico-theological argument, also known as the argument from design, or intelligent design argument is an argument for the existence of God or, more generally, for an intelligent creator based on perceived evidence of deliberate design in the natural world.[1][2][3] The earliest recorded versions of this argument are associated with Socrates in ancient Greece, although it has been argued that he was taking up an older argument.[4][5] Plato, his student, and Aristotle, Plato's student, developed complex approaches to the proposal that the cosmos has an intelligent cause, but it was the Stoics who, under their influence, "developed the battery of creationist arguments broadly known under the label 'The Argument from Design'".[6] From its beginning, there have been numerous criticisms of the different versions of the teleological argument, and responses to its challenge to the claims against non-teleological natural science.

Stoicism. School of Hellenistic Greek philosophy Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy which was founded by Zeno of Citium, in Athens, in the early 3rd century BC. Stoicism is a philosophy of personal ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world. According to its teachings, as social beings, the path to eudaimonia (happiness) for humans is found in accepting the moment as it presents itself, by not allowing oneself to be controlled by the desire for pleasure or fear of pain, by using one's mind to understand the world and to do one's part in nature's plan, and by working together and treating others fairly and justly.

Stoicism flourished throughout the Roman and Greek world until the 3rd century AD, and among its adherents was Emperor Marcus Aurelius. It experienced a decline after Christianity became the state religion in the 4th century AD. Epicurus. Atomism. World view. Worldview remains a confused and confusing concept in English, used very differently by linguists and sociologists. It is for this reason that James W. Theory of forms. Demiurge. Martin Heidegger. Martin Heidegger (German: [ˈmaɐ̯tiːn ˈhaɪdɛɡɐ]; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher, widely seen as a seminal thinker in the Continental tradition, particularly within the fields of existential phenomenology and philosophical hermeneutics.

From his beginnings as a Catholic academic, he developed a groundbreaking and widely influential philosophy. His relationship with Nazism has been a controversial and widely debated subject. For Heidegger, the things in lived experience always have more to them than what we can see; accordingly, the true nature of being is “withdrawal”. Ionian School. Anaximenes of Miletus. Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosopher. Thales of Miletus. Milesian school. Miletus. Natural philosophy. Anaxagoras. Anaxagoras. Goethe, Portrait of the Artist Ilse Graham. Goethe, Portrait of the Artist - Ilse Graham. Johann von Goethe to Charlotte von Stein.

Charlotte von Stein. Charlotte von Stein. Charlotte Buff. Charlotte von Stein. Charlotte Buff-Kestner. The Sorrows of Young Werther.