Delicate insect antennae or the tingling Ampullae of Lorenzini in cartilaginous fishes are some examples of senses that human beings cannot physically perceive. We also cannot detect the nuances within pheromones, the main pathway for animal "expression" in many species. Like humans, corvids may owe their smarts to long childhoods. Human beings typically don’t leave the nest until well into our teenage years—a relatively rare strategy among animals.

Primate Intelligence. Researcher decodes prairie dog language, discovers they've been talking about us. You might not think it to look at them, but prairie dogs and humans actually share an important commonality -- and it's not just their complex social structures, or their habit of standing up on two feet (aww, like people).

As it turns out, prairie dogs actually have one of the most sophisticated forms of vocal communication in the natural world, really not so unlike our own. After more than 25 years of studying the calls of prairie dog in the field, one researcher managed to decode just what these animals are saying. And the results show that praire dogs aren't only extremely effective communicators, they also pay close attention to detail. According to Dr.

Shell Game for Animals. Ravens have social abilities previously only seen in humans. Humans and their primate cousins are well known for their intelligence and social abilities.

You hear them called bird-brained, but birds have demonstrated a great deal of intelligence in many tasks. However, little is known about their social skills. A new study shows that ravens are socially savvier than we give them credit for. They are able to work out the social dynamics of other raven groups, something which only humans had shown the ability to do. Bullying in the community Jorg Massen and his colleagues of the University of Vienna wanted to find out more about about bird's social skills, so they studied ravens, which live in social groups.

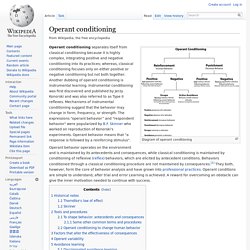

Ravens within a community squabble over their ranking in the group, as higher ranked ravens have better access to food and other resources. Dolphins Understand Syntax. Operant conditioning. Diagram of operant conditioning Operant conditioning separates itself from classical conditioning because it is highly complex, integrating positive and negative conditioning into its practices; whereas, classical conditioning focuses only on either positive or negative conditioning but not both together.

Another dubbing of operant conditioning is instrumental learning. Instrumental conditioning was first discovered and published by Jerzy Konorski and was also referred to as Type II reflexes. Mechanisms of instrumental conditioning suggest that the behavior may change in form, frequency, or strength.

The expressions “operant behavior” and “respondent behavior" were popularized by B.F. Alex, the talking research African Grey. Do Dogs Speak Human? What's the Big Idea?

Perhaps the better question is, do humans speak dog? Either way, the debate over whether language is unique to humans, or a faculty also possessed by wild and domestic animals from dogs to apes to dolphins, is an interesting one. The answer depends on exactly how we define "language," and who's doing the talking, says David Bellos, the Booker prize-winning translator.

Watch our video interview with David Bellos: Animal signalling systems are not (as far as we can tell) as complex as human language, nor do they fit the linguist's definition of a language -- the existence of grammar, syntax, and sound units. But dogs do have many ways of telling us things. To acquire language, kids use a strategy called "fast mapping" -- forming quick, rough hypotheses about the meaning of new words after just one or two exposures. Four weeks after the initial exposure, Rico was still able to retrieve the items by name. What's the Significance? Thinking the Way Animals Do. By Temple Grandin, Ph.D.

Department of Animal Science Colorado State University Western Horseman, Nov. 1997, pp.140-145 (Updated January 2015) Temple Grandin is an assistant professor of animal science at Colorado State University. She is the author of the book Thinking in Pictures. Donnie (dog) Donnie is a Doberman Pinscher dog who came to the attention of science due to his penchant for arranging his plush toys in geometric forms.[1] His owner rescued him from an animal shelter, and at first he was slow to learn, and very reluctant to interact socially with her.[2] He has appeared on the National Geographic Channel’s Dog Genius show.[1][3] On the show, he is shown arranging some of his 80 plush toys into evenly-spaced triangles and lines, and chooses to use, for example, only stuffed frogs or monkeys for a particular design.[4] He is shown creating his arrangements in his large yard in Maryland on remote video cameras without humans being present.

He is even said to create social vignettes with the toys.[4][5] For example, the day after he first allowed his owner to put her arm around him, he placed a large bear with its arm around a smaller frog.[2][6] Dr. ACP - Cephalopods. Self-awareness (in non-human animals) Capacity for introspection and individuation as a subject In philosophy of self, self-awareness is the experience of one's own personality or individuality.[1][2] It is not to be confused with consciousness in the sense of qualia.

While consciousness is being aware of one's environment and body and lifestyle, self-awareness is the recognition of that awareness.[3] Self-awareness is how an individual consciously knows and understands their own character, feelings, motives, and desires. There are two broad categories of self-awareness: internal self-awareness and external self-awareness.[4] Neurobiological basis[edit] Introduction[edit] There are questions regarding what part of the brain allows us to be self-aware and how we are biologically programmed to be self-aware.

Body[edit] Bodily (self-)awareness is related to proprioception and visualization. Health[edit]