Tiān’ānmén Square. Flanked by stern 1950s Soviet-style buildings and ringed by white perimeter fences, the world’s largest public square (440,000 sq metres) is an immense flatland of paving stones at the heart of Běijīng.

If you get up early, you can watch the flagraising ceremony at sunrise, performed by a troop of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldiers drilled to march at precisely 108 paces per minute, 75cm per pace. The soldiers emerge through the Gate of Heavenly Peace to goosestep impeccably across Chang’an Jie; all traffic is halted. The same ceremony in reverse is performed at sunset. Here one stands at the symbolic centre of the Chinese universe.

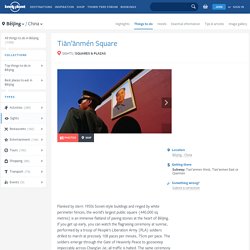

The rectangular arrangement, flanked by halls to both east and west, to some extent echoes the layout of the Forbidden City: as such, the square employs a conventional plan that pays obeisance to traditional Chinese culture, but many of its ornaments and buildings are Soviet- inspired. Summer Palace. As mandatory a Běijīng sight as the Great Wall or the Forbidden City, the Summer Palace was the playground for emperors fleeing the suffocating summer torpor of the old imperial city.

A marvel of design, the palace – with its huge lake and hilltop views – offers a pastoral escape into the landscapes of traditional Chinese painting. It merits an entire day’s exploration, although a (high-paced) morning or afternoon exploring the temples, gardens, pavilions, bridges and corridors may suffice. The domain had long been a royal garden before being considerably enlarged and embellished by Emperor Qianlong in the 18th century. He marshalled a 100,000-strong army of labourers to deepen and expand Kūnmíng Lake (昆明湖; Kūnmíng Hú), and reputedly surveyed imperial navy drills from a hilltop perch. Anglo-French troops vandalised the palace during the Second Opium War (1856–60).

Glittering Kūnmíng Lake swallows up three-quarters of the park, overlooked by Longevity Hill (万寿山; Wànshòu Shān). Yang’s Fry Dumplings. The city’s most famous sesame-seed-and-scallion-coated fried dumplings (生煎; shēngjiān ) unquestionably belong to Yang’s.

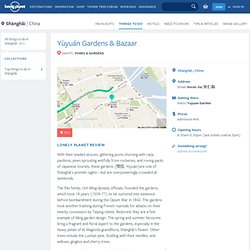

Lines here can stretch to the horizon as eager diners wait for their scalding shēngjiān to be dished out onto vintage communist-era enamel dishes – this isn’t some sort of retro fashion statement, they just never bothered to upgrade the tableware. Order at the left counter – eight dumplings and a soup (汤; tāng ) should be enough – then join the queue on the right to pick up your order. Yùyuán Gardens & Bazaar. With their shaded alcoves, glittering pools churning with carp, pavilions, pines sprouting wistfully from rockeries, and roving packs of Japanese tourists, these gardens (豫园; Yùyuán)are one of Shànghǎi's premier sights – but are overpoweringly crowded at weekends.

The Pan family, rich Ming-dynasty officials, founded the gardens, which took 18 years (1559–77) to be nurtured into existence before bombardment during the Opium War in 1842. The gardens took another trashing during French reprisals for attacks on their nearby concession by Taiping rebels. Restored, they are a fine example of Ming garden design. The spring and summer blossoms bring a fragrant and floral aspect to the gardens, especially in the heavy petals of its Magnolia grandiflora, Shànghǎi's flower. Other trees include the Luohan pine, bristling with thick needles, and willows, gingkos and cherry trees. Shànghǎi Museum.

This must-see Museum guides you through the craft of millennia while simultaneously escorting you through the pages of Chinese history.

Expect to spend half, if not most of, a day here (note that entrance is from East Yan'an Rd). Designed to resemble the shape of an ancient Chinese dǐng vessel, the building is home to one of the most impressive collections in China. Take your pick from the archaic green patinas of the Ancient Chinese Bronzes Gallery through to the silent solemnity of the Ancient Chinese Sculpture Gallery; from the exquisite beauty of the ceramics in the Zande Lou Gallery to the measured and timeless flourishes captured in the Chinese Calligraphy Gallery. Chinese painting, seals, jade, Ming and Qing furniture, coins and ethnic costumes are also on offer in this museum, intelligently displayed in well-lit galleries.

Seats are provided outside galleries on each floor for when lethargy strikes. Shànghǎi Museum. Old Street. A renovated Qing-dynasty stretch of Fangbang Rd lined with specialist tourist shops, this is an excellent place for souvenirs and vendors are less pushy than at Yùyuán Bazaar.