Frederick Twort. Frederick William Twort FRS[3] (22 October 1877 – 20 March 1950) was an English bacteriologist and was the original discoverer in 1915 of bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria).[4] He studied medicine at St Thomas's Hospital, London, was superintendent of the Brown Institute for Animals (a pathology research centre), and was a professor of bacteriology at the University of London.

He researched into Johne's disease, a chronic intestinal infection of cattle, and also discovered that vitamin K is needed by growing leprosy bacteria.[5][6] Early life and scientific training[edit] The eldest of the eleven children of Dr. William Henry Twort, Frederick Twort was born in Camberley, Surrey on 22 October 1877.[3] The three eldest sons went to Tomlinson's Modern School in Woking.[7] From 1894 Frederick studied medicine at St Thomas's Hospital, London. Major work[edit] Mutation[edit] Growth factors[edit] Leprosy was still a major concern during the early part of the 20th century. To save a girl’s life, researchers injected her with genetically engineered viruses. Even before Rebekah Dedrick unpacked the samples, the countdown had already begun.

Some 4,000 miles from her lab in Pittsburgh, at the Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, a 15-year-old girl with cystic fibrosis was battling a life-threatening infection. After receiving a double lung transplant, the young patient had been put on a regimen of immunosuppressive drugs, and an obstinate bacterium called Mycobacterium abscessus had taken hold. The microbes proved resistant to every antibiotic the girl’s doctors tried, and were now spreading throughout her body.

In a last-ditch effort, the London medical team shipped tubes teeming with bacteria isolated from the patient to Dedrick and her colleagues, microbiologists at the University of Pittsburgh. The samples came with an urgent—and radical—request: Identify a swarm of viruses that could be injected into the girl’s body to kill the drug-resistant bacteria. It was risky move.

There was just one catch. Until one day, they didn’t. Képtalálat a következőre: „frederick william twort. Résultats Google de recherche d'images correspondant à. Video: Fighting Infection with Phages. Synthetic phages with programmable specificity. ETH researchers are using synthetic biology to reprogram bacterial viruses—commonly known as bacteriophages—to expand their natural host range.

This technology paves the way for the therapeutic use of standardized, synthetic bacteriophages to treat bacterial infections. Bacteriophages ("phages" for short) are viruses that infect bacteria. Phages are highly host-specific and will typically only infect and kill an individual species or even subspecies of bacteria. Compared to conventional antibiotics, phages do not indiscriminately kill bacteria. Therefore when used as a therapeutic, phages do not cause collateral damage to beneficial "good" bacteria living in the gut.

However, the high specificity of phages is also a disadvantage: Clinicians have to administer different combinations of phages to be sure the right phage is present to target a single bacterial infection. Genetically modified phages Phage cocktail as a form of therapy A long road ahead More information: Matthew Dunne et al. Képtalálat a következőre: „bacteriophage infecting bacteria. Antibiotic resistance. Introduction Antibiotics are medicines used to prevent and treat bacterial infections.

Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria change in response to the use of these medicines. Bacteria, not humans or animals, become antibiotic-resistant. These bacteria may infect humans and animals, and the infections they cause are harder to treat than those caused by non-resistant bacteria. Antibiotic resistance leads to higher medical costs, prolonged hospital stays, and increased mortality.

The world urgently needs to change the way it prescribes and uses antibiotics. Képtalálat a következőre: „bacteriophage. Bacteriophages (article) The Deadliest Being on Planet Earth – The Bacteriophage. T4 Phage attacking E.coli. Képtalálat a következőre: „superbug. Infographic on how antibiotic resistance evolves and spread. Antimicrobial resistance.

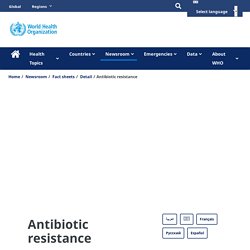

Ability of a microbe to resist the effects of medication Antibiotic resistance tests: Bacteria are streaked on dishes with white disks, each impregnated with a different antibiotic.

Clear rings, such as those on the left, show that bacteria have not grown—indicating that these bacteria are not resistant. The bacteria on the right are fully resistant to all but two of the seven antibiotics tested.[1] Antimicrobial resistance (AMR or AR) is the ability of a microbe to resist the effects of medication that once could successfully treat the microbe.[2][3][4] The term antibiotic resistance (AR or ABR) is a subset of AMR, as it applies only to bacteria becoming resistant to antibiotics.[3] Resistant microbes are more difficult to treat, requiring alternative medications or higher doses of antimicrobials.

These approaches may be more expensive, more toxic or both. Definition[edit] Diagram showing the difference between non-resistant bacteria and drug resistant bacteria. 7 of the deadliest superbugs.