Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a bacterium responsible for several difficult-to-treat infections in humans.

It is also called oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ORSA). MRSA is any strain of Staphylococcus aureus that has developed, through the process of natural selection, resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, which include the penicillins (methicillin, dicloxacillin, nafcillin, oxacillin, etc.) and the cephalosporins.

Strains unable to resist these antibiotics are classified as methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, or MSSA. The evolution of such resistance does not cause the organism to be more intrinsically virulent than strains of Staphylococcus aureus that have no antibiotic resistance, but resistance does make MRSA infection more difficult to treat with standard types of antibiotics and thus more dangerous. Signs and symptoms[edit] In most patients, MRSA can be detected by swabbing the nostrils and isolating the bacteria found inside.

New compound defeats drug-resistant bacteria. Chemists at Brown University have synthesized a new compound that makes drug-resistant bacteria susceptible again to antibiotics.

The compound -- BU-005 -- blocks pumps that a bacterium employs to expel an antibacterial agent called chloramphenicol. Researchers develop MRSA-killing paint. Building on an enzyme found in nature, researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have created a nanoscale coating for surgical equipment, hospital walls, and other surfaces which safely eradicates methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), the bacteria responsible for antibiotic resistant infections. 'We're building on nature,' said Jonathan S.

Dordick, the Howard P. Isermann Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering, and director of Rensselaer's Centre for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies. 'Here we have a system where the surface contains an enzyme that is safe to handle, doesn't appear to lead to resistance, doesn't leach into the environment, and doesn't clog up with cell debris. Epilepsy. Epilepsy cannot be cured, but seizures are controllable with medication in about 70% of cases.[5] In those whose seizures do not respond to medication, surgery, neurostimulation or dietary changes may be considered.

Not all cases of epilepsy are lifelong, and a substantial number of people improve to the point that medication is no longer needed. About 1% of people worldwide (65 million) have epilepsy,[6] and nearly 80% of cases occur in developing countries.[3] Epilepsy becomes more common as people age.[7][8] In the developed world, onset of new cases occurs most frequently in infants and the elderly;[9] in the developing world this is in older children and young adults,[10] due to differences in the frequency of the underlying causes. Neuroscientists produce guide for using ultrasound to treat brain disorders in clinical emergencies. The discovery that low-intensity, pulsed ultrasound can be used to noninvasively stimulate intact brain circuits holds promise for engineering rapid-response medical devices.

Spinal muscular atrophy. Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an autosomal recessive disease caused by a genetic defect in the SMN1 gene, which encodes SMN, a protein widely expressed in all eukaryotic cells.

SMN1 is apparently selectively necessary for survival of motor neurons, as diminished abundance of the protein results in death of neuronal cells in the anterior horn of the spinal cord and subsequent system-wide muscle wasting (atrophy). Spinal muscular atrophy manifests in various degrees of severity which all have in common general muscle wasting and mobility impairment.

Other body systems may be affected as well, particularly in early-onset forms. SMA is the most common genetic cause of infant death. Signs and symptoms[edit] The symptoms vary greatly depending on the SMA type involved, the stage of the disease and individual factors and commonly include: Causes[edit] New insight into fatal spinal disease. Researchers at the University of Missouri have identified a communication breakdown between nerves and muscles in mice that may provide new insight into the debilitating and fatal human disease known as spinal muscular atrophy (SMA).

"Critical communication occurs at the point where nerves and muscles 'talk' to each other. When this communication between nerves and muscles is disrupted, muscles do not work properly," said Michael Garcia, associate professor of biological sciences in the College of Arts and Science and the Bond Life Sciences Center.

Sickle-cell disease. Sickle-cell disease (SCD), or sickle-cell anaemia (SCA) or drepanocytosis, is a hereditary blood disorder, characterized by red blood cells that assume an abnormal, rigid, sickle shape.

Sickling decreases the cells' flexibility and results in a risk of various life-threatening complications. This sickling occurs because of a mutation in the haemoglobin gene. Correcting sickle cell disease with stem cells. Using a patient's own stem cells, researchers at Johns Hopkins have corrected the genetic alteration that causes sickle cell disease (SCD), a painful, disabling inherited blood disorder that affects mostly African-Americans.

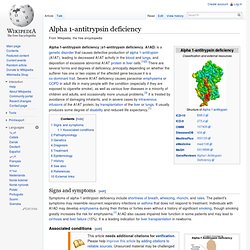

The corrected stem cells were coaxed into immature red blood cells in a test tube that then turned on a normal version of the gene. The research team cautions that the work, done only in the laboratory, is years away from clinical use in patients, but should provide tools for developing gene therapies for SCD and a variety of other blood disorders. In an article published online August 31 in Blood, the researchers say they are one step closer to developing a feasible cure or long-term treatment option for patients with SCD, which is caused by a single DNA letter change in the gene for adult hemoglobin, the principle protein in red blood cells needed to carry oxygen. Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Signs and symptoms[edit] Symptoms of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency include shortness of breath, wheezing, rhonchi, and rales.

The patient's symptoms may resemble recurrent respiratory infections or asthma that does not respond to treatment. Individuals with A1AD may develop emphysema during their thirties or forties even without a history of significant smoking, though smoking greatly increases the risk for emphysema.[1] A1AD also causes impaired liver function in some patients and may lead to cirrhosis and liver failure (15%). NIH funded researchers correct sickle cell disease in adult mice. Embargoed for Release Thursday, October 13, 2011 2 p.m.

EDT National Institutes of Health-funded scientists have corrected sickle cell disease in adult laboratory mice by activating production of a special blood component normally produced before, but not after, birth. "This discovery provides an important new target for future therapies in people with sickle cell disease," said Susan B. Shurin, M.D., acting director of the NIH's National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, which co-funded the study. Scientists correct the typo behind a genetic liver disease. Every year, thousands of people die because of typos in their genes. There’s a long list of debilitating or fatal genetic diseases that are caused by a single incorrect DNA letter among the three billion in our genome. It’s the equivalent of pulping an entire encyclopaedia on the basis of a single typo.

But hope is at hand. Fighting Fire With Fire: 'Vampire' Bacteria Has Potential as Living Antibiotic. Listen to the UVA Today Radio Show report on this story by Fariss Samarrai: October 31, 2011 — A vampire-like bacteria that leeches onto specific other bacteria – including certain human pathogens – has the potential to serve as a living antibiotic for a range of infectious diseases, a new study indicates.

The bacterium, Micavibrio aeruginosavorus, was discovered to inhabit wastewater nearly 30 years ago, but has not been extensively studied because it is difficult to culture and investigate using traditional microbiology techniques. However, biologists in the University of Virginia's College of Arts & Sciences, Martin Wu and graduate student Zhang Wang, have decoded its genome and are learning "how it makes its living," Wu said. The bacterium "makes its living" by seeking out prey – certain other bacteria – and then attaching itself to its victim's cell wall and essentially sucking out nutrients.

Retinitis pigmentosa. Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is an inherited, degenerative eye disease that causes severe vision impairment and often blindness.[1] The progress of RP is not consistent. Some people will exhibit symptoms from infancy, others may not notice symptoms until later in life.[2] Generally, the later the onset, the more rapid is the deterioration in sight. UF researchers develop gene therapy that could correct a common form of blindness » Health Science Center News & Communications. A new gene therapy method developed by University of Florida researchers, William W. Hauswirth, Ph.D. and Alfred S. Lewin, Ph.D., has the potential to reverse a common form of blindness that strikes young children. A new gene therapy method developed by University of Florida researchers has the potential to treat a common form of blindness that strikes both youngsters and adults.

The technique works by replacing a malfunctioning gene in the eye with a normal working copy that supplies a protein necessary for light-sensitive cells in the eye to function. Progeria. Progeria Patients May Find Hope in New Drug. Croatian scientist gives new hope to rapidly ageing children. Progeria Research Foundation.