La fallace inversione dell'onere della prova ©Ssosay Vi è mai capitato, alla vostra richiesta di prove che supportino una certa asserzione, per esempio «tutto è un sogno», di sentirvi rispondere «prova a dimostrare che non lo è»? Oppure di sentirvi chiedere di provare che il pianeta Nibiru non esiste quando si cerca solo di criticare le prove della sua esistenza? Sì? Allora vi siete trovati di fronte alla fallacia dell’inversione dell’onere della prova, ossia quella strategia scorretta in cui l’interlocutore, al vostro dubbio verso la sua asserzione, chiede a voi di provare il contrario. Andiamo per gradi. Per il nostro discorso è importante riconoscere che in entrambi questi casi troviamo almeno una persona che asserisce. Sebbene varii da contesto a contesto[3] nella discussione critica, ossia nelle discussioni in cui la prova delle reciproche tesi avviene attraverso l’argomentazione razionale, l’onere della prova impone che chi asserisce si assuma l’impegno di provare, qualora richiesto, la propria asserzione. Conclusione Note

List of Internet forums Wikipedia list article An Internet forum, or message board, is an online discussion site where people can hold conversations in the form of posted messages.[1] Forums act as centralized locations for topical discussion. Forums are an element of social media technologies which take on many different forms including blogs, business networks, enterprise social networks, forums, microblogs, photo sharing, products/services review, social bookmarking, social gaming, social networks, video sharing and virtual worlds.[3][verification needed] IGN Boards[11] Quora XDA-Developers Zhihu See also Further reading References

60 Small Ways to Improve Your Life in the Next 100 Days Contrary to popular belief, you don’t have to make drastic changes in order to notice an improvement in the quality of your life. At the same time, you don’t need to wait a long time in order to see the measurable results that come from taking positive action. All you have to do is take small steps, and take them consistently, for a period of 100 days. Below you’ll find 60 small ways to improve all areas of your life in the next 100 days. Home 1. Day 1: Declutter MagazinesDay 2: Declutter DVD’sDay 3: Declutter booksDay 4: Declutter kitchen appliances 2. If you take it out, put it back.If you open it, close it.If you throw it down, pick it up.If you take it off, hang it up. 3. A burnt light bulb that needs to be changed.A button that’s missing on your favorite shirt.The fact that every time you open your top kitchen cabinet all of the plastic food containers fall out. Happiness 4. 5. 6. How many times do you beat yourself up during the day? 7. Learning/Personal Development 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13.

Fallacies Dr. Michael C. Labossiere, the author of a Macintosh tutorial named Fallacy Tutorial Pro 3.0, has kindly agreed to allow the text of his work to appear on the Nizkor site, as a Nizkor Feature. It remains © Copyright 1995 Michael C. Labossiere, with distribution restrictions -- please see our copyright notice. Other sites that list and explain fallacies include: Constructing a Logical Argument Description of Fallacies In order to understand what a fallacy is, one must understand what an argument is. There are two main types of arguments: deductive and inductive. A fallacy is, very generally, an error in reasoning.

Critical thinking web We have over 100 online tutorials on different aspects of thinking skills. They are organized into modules listed below and in the menu above. Our tutorials are used by universities, community colleges, and high schools around the world. The tutorials are completely free and under a Creative Commons license. More info Maintained by Joe Lau, Philosophy Department, University of Hong Kong. Companion textbook An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity: Think More, Think Better. Other books on critical thinking and related topics Chinese version of this site 思方網 (Traditional Chinese) 思方网 (Simplified Chinese)

Why People "Fly from Facts" “There was a scientific study that showed vaccines cause autism.” “Actually, the researcher in that study lost his medical license, and overwhelming research since then has shown no link between vaccines and autism.” “Well, regardless, it’s still my personal right as a parent to make decisions for my child.” Does that exchange sound familiar: a debate that starts with testable factual statements, but then, when the truth becomes inconvenient, the person takes a flight from facts. As public debate rages about issues like immunization, Obamacare, and same-sex marriage, many people try to use science to bolster their arguments. And since it’s becoming easier to test and establish facts—whether in physics, psychology, or policy—many have wondered why bias and polarization have not been defeated. Our new research, recently published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, examined a slippery way by which people get away from facts that contradict their beliefs.

quora 25 clever ideas to make life easier Via: amy-newnostalgia.blogspot.com Why didn’t I think of that?! We guarantee you’ll be uttering those words more than once at these ingenious little tips, tricks and ideas that solve everyday problems … some you never knew you had! (Above: hull strawberries easily using a straw). Via: apartmenttherapy.com Rubbing a walnut over scratches in your furniture will disguise dings and scrapes. Via: unplggd.com Remove crayon masterpieces from your TV or computer screen with WD40 (also works on walls). Via: athomewithrealfood.blogspot.com Stop cut apples browning in your child’s lunch box by securing with a rubber band. Via: marthastewart.com Overhaul your linen cupboard – store bedlinen sets inside one of their own pillowcases and there will be no more hunting through piles for a match. Via: realsimple.com Pump up the volume by placing your iPhone / iPod in a bowl – the concave shape amplifies the music. Via: savvyhousekeeping.com Re-use a wet-wipes container to store plastic bags. Via: iheartnaptime.net

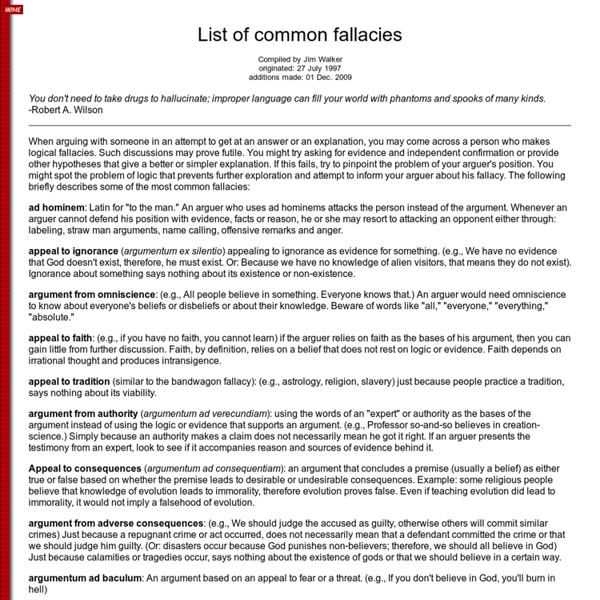

List of fallacies A fallacy is incorrect argument in logic and rhetoric resulting in a lack of validity, or more generally, a lack of soundness. Fallacies are either formal fallacies or informal fallacies. Formal fallacies[edit] Main article: Formal fallacy Appeal to probability – is a statement that takes something for granted because it would probably be the case (or might be the case).[2][3]Argument from fallacy – assumes that if an argument for some conclusion is fallacious, then the conclusion is false.Base rate fallacy – making a probability judgment based on conditional probabilities, without taking into account the effect of prior probabilities.[5]Conjunction fallacy – assumption that an outcome simultaneously satisfying multiple conditions is more probable than an outcome satisfying a single one of them.[6]Masked man fallacy (illicit substitution of identicals) – the substitution of identical designators in a true statement can lead to a false one. Propositional fallacies[edit]

Make Sure You’re Solving the Right Problem It may be obvious that you can’t solve a problem that’s not well defined, but many people neglect this detail. Next time you think you’re ready to go into problem-solving mode, consider the following: Establish the basic need for a solution. Adapted from “Are You Solving the Right Problem?” Visit Harvard Business Review’s Management Tip homepage Purchase the HBR Management Tips book Anti-pattern Da Wikipedia, l'enciclopedia libera. In informatica, gli anti-pattern (o antipattern) sono dei design pattern, o più in generale delle procedure o modi di fare, usati durante il processo di sviluppo del software, che pur essendo lecitamente utilizzabili, si rivelano successivamente inadatti o controproduttivi nella pratica. Il termine fu coniato nel 1995 da Andrew Koenig, ispirato dal libro Design Patterns: Elementi per il riuso di software ad oggetti scritto dalla Gang of four (la banda dei quattro), i quali svilupparono il concetto di pattern nel campo del software. Secondo l'autore, devono presentarsi almeno due elementi chiave per poter distinguere un anti-pattern da un semplice errore logico o cattiva pratica: Qualche schema ricorrente di azioni, processi o strutture che inizialmente appaiono essere di beneficio, ma successivamente producono più problemi che benefici.L'esistenza di una soluzione alternativa che è chiaramente documentata, collaudata nella pratica e ripetibile.

ReBirth: The Pursuit of Porsha – Reconnecting with The Darkness in the Light Children Educate Themselves III: The Wisdom of Hunter-Gatherers For hundreds of thousands of years, up until the time when agriculture was invented (a mere 10,000 years ago), we were all hunter-gatherers. Our human instincts, including all of the instinctive means by which we learn, came about in the context of that way of life. And so it is natural that in this series on children's instinctive ways of educating themselves I should ask: In the last half of the 20th century, anthropologists located and observed many groups of people—in remote parts Africa, Asia, Australia, New Guinea, South America, and elsewhere—who had maintained a hunting-and-gathering life, almost unaffected by modern ways. Although each group studied had its own language and other cultural traditions, the various groups were found to be similar in many basic ways, which allows us to speak of "the hunter-gatherer way of life" in the singular. What I learned from my reading and our questionnaire was startling for its consistency from culture. • "[!