Maritime Southeast Asia: A Game of Go? How much does the ancient game of Go, or weiqi, reveal about Chinese military strategy?

Over at The National Interest last week, Asia-Pacific Center professor Alexander Vuving ran a nifty longish essay explaining China’s grand strategy in the South China Sea in terms of the Japanese game Go, or weiqi as the Chinese call it. It’s well worth your time. Read the whole thing. Choose Backlog Items that Serve 2 Purposes. AIs Have Mastered Chess. Will Go Be Next? Chou Chun-hsun, one of the world’s top players of the ancient game of Go, sat hunched over a board covered with a grid of closely spaced lines.

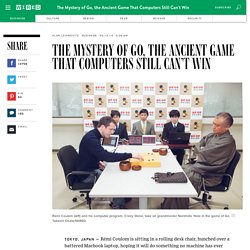

To the untrained eye, the bean-size black and white stones scattered across the board formed a random design. To Chou, each stone was part of a complex campaign between two opposing forces that were battling to capture territory. The Go master was absorbed in thought as he considered various possibilities for his next move and tried to visualize how each option would affect the course of the game. The Mystery of Go, the Ancient Game That Computers Still Can’t Win. TOKYO, JAPAN — Rémi Coulom is sitting in a rolling desk chair, hunched over a battered Macbook laptop, hoping it will do something no machine has ever done.

That may take another ten years or so, but the long push starts here, at Japan’s University of Electro-Communications. The venue is far from glamorous — a dingy conference room with faux-wood paneling and garish fluorescent lights — but there’s still a buzz about the place. Spectators are gathered in front of an old projector screen in the corner, and a ragged camera crew is preparing to broadcast the tournament via online TV, complete with live analysis from two professional commentators.

Coulom is wearing the same turtleneck sweater and delicate rimless glasses he wore at last year’s competition, and he’s seated next to his latest opponent, an ex-pat named Simon Viennot who’s like a younger version of himself — French, shy, and self-effacing. They aren’t looking at each other. The challenge is daunting. And so it does. What can a game tell us about China's politics? Los algoritmos de verdad saben que el ajedrez es un juego de niños: el desafío es el Go. Igual a muchos el nombre de Go no les suena a nada.

Es un juego asiático muy tradicional donde dos jugadores tienen que colocar piedras negras y blancas sobre las intersecciones libres de una cuadrícula que puede variar de tamaño según el nivel de la partida. Parece sencillo pero este juego tradicional chino tiene una grandísima estrategia al margen de usar unas reglas realmente sencillas. Para los estudiosos en la creación de inteligencia artificial para crear programas de juego por ordenador, es un equivalente al ajedrez. Si con Deep Blue, y toda la polémica alrededor, vimos que la máquina pudo batir a uno de los mejores jugadores de la historia. Neuroscience applied to go. Written by alejo on March 29th, 2014.

The Electronic Holy War. In May, 1997, I.B.M.’s Deep Blue supercomputer prevailed over Garry Kasparov in a series of six chess games, becoming the first computer to defeat a world-champion chess player.

Chess and GO no-brainers? On-Line Samurai Transform an Ancient Game. THE Asian board game of Go was the game of the samurai.

Among noble accomplishments for Chinese gentlemen, Go ranked with calligraphy, poetry and music. For centuries, Go has been used as a tool to teach military strategy. It is the game from which Japanese businessmen draw metaphors. In an Ancient Game, Computing's Future. EARLY in the film ''A Beautiful Mind,'' the mathematician John Nash is seen sitting in a Princeton courtyard, hunched over a playing board covered with small black and white pieces that look like pebbles.

He was playing Go, an ancient Asian game. Frustration at losing that game inspired the real Mr. Nash to pursue the mathematics of game theory, research for which he eventually won a Nobel Prize. In recent years, computer experts, particularly those specializing in artificial intelligence, have felt the same fascination -- and frustration. To Test a Powerful Computer, Play an Ancient Game. DEEP BLUE's recent trouncing of Garry Kasparov sent shock waves through the Western world.

In much of the Orient, however, the news that a computer had beaten a chess champion was likely to have been met with a yawn. While there are avid chess players in Japan, China, Korea and throughout the East, far more popular is the deceptively simple game of Go, in which black and white pieces called stones are used to form intricate, interlocking patterns that sprawl across the board.

Research Offers a New Look at Go Players’ Brains. A research collaboration in Seoul has revealed new information about the cognitive requirements of playing go and the effects that it may have on the brain.

A team compared a group of expert go players with a group of beginners and published the results in the journal “Frontiers in Human Neuroscience”. The work revealed several differences between the brains of the beginner and the expert. The experts had increased volume in certain areas of the brain, decreased volume in others, greater interconnectivity between certain regions and differences in the overall brain structure. Alex Wissner-Gross: A new equation for intelligence. Reflex epilepsy induced by playing Go-stop or Baduk games. Received 26 April 2012; received in revised form 19 August 2012; accepted 21 August 2012. published online 19 September 2012. Purpose Seizures can be triggered by complex mental activities. The aim of this study was to investigate the clinical characteristics of reflex epilepsy induced by playing Go-stop or Baduk games.

Methods The study comprised 11 patients with this type of reflex epilepsy identified from our patient database. Results. Baduk alphabet. The Baduk alphabet was invented by Sebastian Groß from Germany and is based on the game of Baduk, which is also known as Go. Notable features Type of writing system: Alphabetic script Dirrection of writing: left to right in more or less vertical columns running from top to bottom. Une contribution à l'apprentissage par renforcement; application au computer Go par Sylvain Gelly.

Analyses de dépendances et méthodes de Monte-Carlo dans les jeux de réflexion. Résumé de la thèse de Bernard Helmstetter. Système d'apprentissage par auto-observation. Application au jeu de Go par Tristan Cazenave. Modélisation cognitive du joueur de Go par Bruno Bouzy. GO. François PETITJEAN, Revue Française de Go, no.11, 1981 Il existe des analogies entre le Go et certaines situations sociales. On le sait depuis longtemps. Réponse à l'article de François Petitjean par Philippe Mercier. Exploring the brains of Baduk (Go) experts: gray matter morphometry, resting-state functional connectivity, and graph theoretical analysis. Ancient board game offers insight into military, cyber threats. UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- As the United States faces increasing cyber and physical threats, both foreign and domestic, intelligence analysts must be able to predict their adversaries’ moves and defeat them at their own games.

At Penn State’s College of Information Sciences and Technology (IST), Stan Aungst is employing the ancient Chinese game of Go to help students gain new insight and new methods for countering attacks and to hone new cognitive skills for the 21st century. “We’re using the game as a training ground to think strategically and tactically,” said Aungst, a senior lecturer for security and risk analysis (SRA) and senior research associate for the Network-Centric Cognition and Information Fusion Center. Go is a board game for two players that originated in China more than 2,500 years ago and spread to Korea and Japan in about the 5th and 7th centuries CE, respectively. “The lessons are more applicable to today’s military situation,” he said.