Metaphysical naturalism. This article is about the worldview.

For the working assumption without suggesting absolute truth, see Methodological naturalism. Metaphysical naturalism, also called ontological naturalism, philosophical naturalism and scientific materialism is a worldview which holds that there is nothing but natural elements, principles, and relations of the kind studied by the natural sciences, i.e., those required to understand our physical environment by mathematical modelling. Perspectivism. View[edit] People always adopt perspectives by default – whether they are aware of it or not – and the concepts of one's existence are defined by the circumstances surrounding that individual.

Truth is made by and for individuals and peoples.[3] This view differs from many types of relativism which consider the truth of a particular proposition as something that altogether cannot be evaluated with respect to an "absolute truth",[citation needed] without taking into consideration culture and context. Interpretation[edit] See also[edit] References[edit] Jump up ^ Mautner, Thomas, The Penguin Dictionary of Philosophy, page 418Jump up ^ Schacht, Richard, Nietzsche, p 61.Jump up ^ Scott-Kakures, Dion, History of Philosophy, page 346Jump up ^ Schacht, Richard, Nietzsche. External links[edit] La Voluntad de ilusión en Nietzsche; bases del perspectivismo| in Konvergencias. Zeitgeist. The Zeitgeist (spirit of the age or spirit of the time) is the intellectual fashion or dominant school of thought that typifies and influences the culture of a particular period in time.

For example, the Zeitgeist of modernism typified and influenced architecture, art, and fashion during much of the 20th century.[1] The German word Zeitgeist is often attributed to the philosopher Georg Hegel, but he never actually used the word. In his works such as Lectures on the Philosophy of History, he uses the phrase der Geist seiner Zeit (the spirit of his time)—for example, "no man can surpass his own time, for the spirit of his time is also his own spirit. "[2] Ioan Scotus Eriugena. Eriugena.

Imagine de pe o bancnotă irlandeză Ioan Scotus Eriugena (815-877) sau Ioan Scottus Eriugena este considerat primul mare gânditor scolastic. Importanța și caracterul inedit al operei lui Eriugena stau în cunoașterea și efortul remarcabil de a introduce în lumea creștină scrierile areopagitice. The Philosopher who believed in the "super-existence" of God. Integral theory. Integral theory, a philosophy with origins in the work of Sri Aurobindo and Jean Gebser, and promoted by Ken Wilber, seeks a synthesis of the best of pre-modern, modern, and postmodern reality.[1] It is portrayed as a "theory of everything,"[2] and offers an approach "to draw together an already existing number of separate paradigms into an interrelated network of approaches that are mutually enriching.

"[1] It has been applied by scholar-practitioners in 35 distinct academic and professional domains as varied as organizational management and art.[1] Methodologies[edit] AQAL, pronounced "ah-qwul," is a widely used framework in Integral Theory. It is also alternatively called the Integral Operating System (IOS) or by various other synonyms. Sri Aurobindo, Jean Gebser, and Ken Wilber, have all made significant theoretical contributions to integral theory. AQAL Theory – Lines. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

History of philosophy. The history of philosophy is the study of philosophical ideas and concepts through time.

Issues specifically related to history of philosophy might include (but are not limited to): How can changes in philosophy be accounted for historically? What drives the development of thought in its historical context? To what degree can philosophical texts from prior historical eras be understood even today? All cultures — be they prehistoric, medieval, or modern; Eastern, Western, religious or secular — have had their own unique schools of philosophy, arrived at through both inheritance and through independent discovery. Such theories have grown from different premises and approaches, examples of which include (but are not limited to) rationalism (theories arrived at through logic), empiricism (theories arrived at through observation), and even through leaps of faith, hope and inheritance (such as the supernaturalist philosophies and religions).

List of philosophies. Existentiell. Though it is not commonly used in philosophy outside of discussions of Heidegger's seminal work Being and Time, it is important to understand Heidegger's definition of the term if one wishes to study Being and Time.

Heidegger distinguishes between his two terms "existential" and "existentiell" in the Introduction to Being and Time. Double-aspect theory. For the Canadian constitutional theory, see Double aspect In the philosophy of mind, double-aspect theory is the view that the mental and the physical are two aspects of, or perspectives on, the same substance.

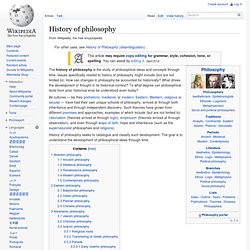

The theory's relationship to neutral monism is ill-defined, but one proffered distinction says that whereas neutral monism allows the context of a given group of neutral elements to determine whether the group is mental, physical, both, or neither, double-aspect theory requires the mental and the physical to be inseparable and mutually irreducible (though distinct).[1] Dual-aspect theory is akin to neutral monism. This diagram contrasts it with physicalism and idealism, as well as Cartesian dualism. Double-aspect theorists include:- See also[edit] Property dualism. Property dualism: the exemplification of two kinds of property by one kind of substance Property dualism describes a category of positions in the philosophy of mind which hold that, although the world is constituted of just one kind of substance - the physical kind - there exist two distinct kinds of properties: physical properties and mental properties.

In other words, it is the view that non-physical, mental properties (such as beliefs, desires and emotions) inhere in some physical substances (namely brains). Emergent Materialism[edit] Emergentism is the idea that increasingly complex structures in the world give rise to the "emergence" of new properties that are something over and above (i.e. cannot be reduced to) their more basic constituents. Anomalous monism. Relation. Relation or Relations may refer to: General use[edit] Kinship, relationship by genealogical originSocial relations, in social science, social interaction between two or more individualsInternational relations, strategies chosen by a state to safeguard its national interests and achieve its foreign policy objectives.

Externalism. Externalism is a group of positions in the philosophy of mind which hold that the mind is not only the result of what is going on inside the nervous system (or the brain) but also of what either occurs or exists outside the subject. It is often contrasted with internalism which holds that the mind emerges from neural activity alone. Externalism articulates the belief that the mind is not just the brain or what the brain does. There are different versions of externalism based both on the strength of the relation, and on what the mind is taken to be.[1] Externalism stresses the importance of factors external to the nervous system. At one extreme, the mind could possibly depend on external factors. At the opposite extreme, the mind depends necessarily on external factors. Pandeism. Pandeism (or pan-deism) is a theological doctrine which combines aspects of pantheism and deism.[1] It holds that the creator of the universe actually became the universe, and so ceased to exist as a separate and conscious entity.[2][3][4][5] Pandeism is proposed to explain, as it relates to deism, why God would create a universe and then abandon it,[6] and as to pantheism, the origin and purpose of the universe.[6][7] A pantheistic form of deism[edit]

Monadology. The Monadology ( La Monadologie , 1714) is one of Gottfried Leibniz ’s best known works representing his later philosophy . It is a short text which sketches in some 90 paragraphs a metaphysics of simple substances , or monads . Zeno's paradoxes. Zeno's arguments are perhaps the first examples of a method of proof called reductio ad absurdum also known as proof by contradiction. They are also credited as a source of the dialectic method used by Socrates.[3] Some mathematicians and historians, such as Carl Boyer, hold that Zeno's paradoxes are simply mathematical problems, for which modern calculus provides a mathematical solution.[4] Some philosophers, however, say that Zeno's paradoxes and their variations (see Thomson's lamp) remain relevant metaphysical problems.[5][6][7] The origins of the paradoxes are somewhat unclear.

Noumenon. Etymology[edit] The Greek word noumenon (νοούμενoν), plural noumena (νοούμενα), is the middle-passive present participle of νοεῖν (noein), "I think, I mean", which in turn originates from the word "nous" (from νόος, νοῦς, perception, understanding, mind). A rough equivalent in English would be "something that is thought", or "the object of an act of thought". Usage in reference to pre-Kantian philosophy[edit] Transcendental idealism. Transcendental idealism is a doctrine founded by German philosopher Immanuel Kant in the 18th century. Kant's doctrine maintains that human experience of things is similar to the way they appear to us — implying a fundamentally subject-based component, rather than being an activity that directly (and therefore without any obvious causal link) comprehends the things as they are in and of themselves. Background[edit] Although it influenced the course of subsequent German philosophy dramatically, exactly how to interpret this concept was a subject of some debate among 20th century philosophers.

Kant first describes it in his Critique of Pure Reason, and distinguished his view from contemporary views of realism and idealism, but philosophers do not agree how sharply Kant differs from each of these positions. Being in itself. Heideggerian terminology.

Being in itself. Being and Nothingness. Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology (French: L'Être et le néant : Essai d'ontologie phénoménologique), sometimes subtitled A Phenomenological Essay on Ontology, is a 1943 book by philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre.[1] Sartre's main purpose is to assert the individual's existence as prior to the individual's essence. His overriding concern in writing the book was to demonstrate that free will exists.[2] In Sartre's much gloomier account in Being and Nothingness, man is a creature haunted by a vision of "completion", what Sartre calls the ens causa sui, literally "a being that causes itself", which many religions and philosophers identify as God. Existence precedes essence. Concept.

Notion (philosophy) A primitive notion is used in logic or mathematics as an undefined term or concept at the foundation of an axiomatic system to be constructed. Doctrine of internal relations. Property (philosophy) Daniel Dennett distinguishes between lovely properties (such as loveliness itself), which, although they require an observer to be recognised, exist latently in perceivable objects; and suspect properties which have no existence at all until attributed by an observer (such as being a suspect in a murder enquiry)[3] Relation (history of concept) Qualia. Explanatory gap. Causality. Consciousness. Mirror test. Emotion in animals. Emotion in animals. Animal consciousness. Animal consciousness. Animal consciousness. Animal consciousness. Subject–object problem.

Philosophy of mind. Dualism (philosophy of mind) Property dualism. Anomalous monism. Double-aspect theory. Dialectical monism. Neutral monism. Gödel metric. Growing block universe. One-Dimensional Man. Existentialism. The Myth of Sisyphus.