Tes. Helping children to learn phonics at home has made a big impression on many parents.

I wonder how much stress and conflict have blown up as parents have understandably struggled with terms like "split digraph"? But in the background, researchers and educators have been fighting "phonics wars" for the best part of a century. Writing in 1934, the early years pioneer Susan Isaacs argued against using phonics to teach reading. She held that "the most natural unit of speech in the young child is the word".

Many of her successors agree. Literacy: Phonics benefits children who struggle with reading It’s surprising that this war continues; the research is conclusive. This matters. In England, younger adults perform no better than older ones. Research in support of phonics Today, we know that effective programmes to teach reading will include a synthetic phonics programme. Learning through Phonics Explanation. How a flawed idea is teaching millions of kids to be poor readers. Molly Woodworth was a kid who seemed to do well at everything: good grades, in the gifted and talented program.

But she couldn't read very well. "There was no rhyme or reason to reading for me," she said. "When a teacher would dictate a word and say, 'Tell me how you think you can spell it,' I sat there with my mouth open while other kids gave spellings, and I thought, 'How do they even know where to begin? ' I was totally lost. " Woodworth went to public school in Owosso, Michigan, in the 1990s. Strategy 1: Memorize as many words as possible. Strategy 2: Guess the words based on context.

Strategy 3: If all else failed, she'd skip the words she didn't know. Reading the brain - what MRI scanning tells us about reading. If information processing theory attempts to articulate the unobservable (Tracey and Morrow, 2012), then it is relevant to explore, with the development of scanning technology, what is observable in the brain when reading occurs.

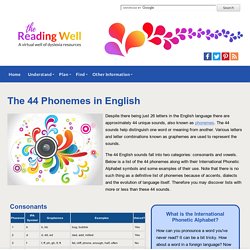

This is particularly relevant if we reject the concept that reading is a natural and inherent process that can be discovered in much the same manner that humans develop language fluency. The first indications that the brain has a specific, specialised, cortical visual centre for letter and word reading emerged from Déjerine’s (1887) discovery that his patient (Mr C.), who could converse articulately, recognise people and objects, read digits and even write, had suddenly become incapable of reading despite having been fluent previously. Mr C. had no visual impairment. What Déjerine (1887) proposed was a simple, linear, serial processing chain for reading. This is crucial for the teaching of reading. RdTch93. Reading A Psycholinguistic Guessing Game. SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class journal research. The 44 Phonemes in English. Despite there being just 26 letters in the English language there are approximately 44 unique sounds, also known as phonemes.

The 44 sounds help distinguish one word or meaning from another. Various letters and letter combinations known as graphemes are used to represent the sounds. The 44 English sounds fall into two categories: consonants and vowels. Below is a list of the 44 phonemes along with their International Phonetic Alphabet symbols and some examples of their use. Note that there is no such thing as a definitive list of phonemes because of accents, dialects and the evolution of language itself. The ill-conceived idea of ‘regular’ and ‘irregular’ spelling – a reprise – The Literacy Blog. This post is a reprise of a post I wrote in February 2016.

As its subject matter seems to crop up all the time in discussions about phonics teaching, I thought it would be helpful to re-post it. What do people mean when they talk about ‘regular’ and ‘irregular’ spellings? ‘Regular’, as the dictionary definition suggests, means ‘arranged in or constituting a constant or definite pattern, … well ordered, well structured, perpetual, constant…’ The problem is that there is only one constant in the spelling system in English and it isn’t the spellings!

It is the forty-four or so sounds in the language; it is sounds that drive the spelling system, not spellings. When people talk about ‘regular’ and irregular’ spellings, it is because they are confused about the nature of the writing system and its relationship to the forty-four or so sounds in the English language. We can, fairly reasonably, say that Spanish, say, is almost ‘regular’. As I’ve said, there are gradations. The Reading Mind: A Cognitive Approach to Understanding How the Mind Reads (0001119301378): Daniel T. Willingham: Books.

The science is clear on what works, argues Clare Sealy, but why don’t more teachers know about it? Nearly every primary school “does” phonics to some degree and it is often seen as a necessary but dull chore, akin to trying to get children to eat some greens when they’d more naturally want to be eating ice cream.

Doubts over whether it is the “right” thing for children to be doing still lurk in some quarters, too. Does awareness of speech as a sequence of phones arise spontaneously?