Achamán. Achamán is the supreme god of the Guanches on the island of Tenerife; he is the father god and creator.

The name means literally "the skies", in allusion to the celestial vault (the sky). Achamán, an omnipotent and eternal god, created the land and the water, the fire and the air, and all creatures derived their existence from him. Achamán lived in the heights and sometimes descended upon the summits of the mountains, contemplating his creations. According to legend, Guayota kidnapped Magec (the sun) and shut it up in the Teide, plunging the world into darkness.

Humans prayed to Achamán who saved Magec, and instead locked Guayota up in the Teide. Other names of Achamán are: AchuhuranAchahucanacAchguayaxeraxAchoronAchaman On other islands, its name also varied: Acoran (Gran Canaria) or Abora (La Palma) among others.Guanche Religion. Achuhucanac. Amun. "Amen Ra" redirects here.

For the Belgian band, see Amenra. Amun (also Amon (/ˈɑːmən/), Amen; Ancient Greek: Ἄμμων Ámmōn, Ἅμμων Hámmōn) was a major Egyptian deity. He was attested since the Old Kingdom together with his spouse Amaunet. With the 11th dynasty (c. 21st century BC), he rose to the position of patron deity of Thebes by replacing Monthu.[1] Anhur. Anhur was depicted wearing a headdress of two or four tall feathers.[1] In early Egyptian mythology, Anhur (also spelled Onuris, Onouris, An-Her, Anhuret, Han-Her, Inhert) was originally a god of war who was worshipped in the Egyptian area of Abydos, and particularly in Thinis.

Myths told that he had brought his wife, Mehit, who was his female counterpart, from Nubia, and his name reflects this—it means (one who) leads back the distant one.[2] One of his titles was Slayer of Enemies. Anhur was depicted as a bearded man wearing a robe and a headdress with four feathers, holding a spear or lance, or occasionally as a lion-headed god (representing strength and power). Badessy. Denka. This article is about the African mythology.

For Ethnic Group, see Dinka. Hathor. Hathor (/ˈhæθɔr/ or /ˈhæθər/;[2] Egyptian: ḥwt-ḥr and from Greek: Άθωρ, "mansion of Horus")[1] is an Ancient Egyptian goddess who personified the principles of joy, feminine love, and motherhood.[3] She was one of the most important and popular deities throughout the history of Ancient Egypt.

Hathor was worshiped by Royalty and common people alike in whose tombs she is depicted as "Mistress of the West" welcoming the dead into the next life.[4] In other roles she was a goddess of music, dance, foreign lands and fertility who helped women in childbirth,[4] as well as the patron goddess of miners.[5] The cult of Hathor predates the historic period, and the roots of devotion to her are therefore difficult to trace, though it may be a development of predynastic cults which venerated fertility, and nature in general, represented by cows.[6] Hathor is commonly depicted as a cow goddess with horns in which is set a sun disk with Uraeus. Early depictions[edit] Temples[edit] Hesat[edit] Notes[edit]

Horus. Horus is one of the oldest and most significant deities in ancient Egyptian religion, who was worshipped from at least the late Predynastic period through to Greco-Roman times.

Different forms of Horus are recorded in history and these are treated as distinct gods by Egypt specialists.[1] These various forms may possibly be different perceptions of the same multi-layered deity in which certain attributes or syncretic relationships are emphasized, not necessarily in opposition but complementary to one another, consistent with how the Ancient Egyptians viewed the multiple facets of reality.[2] He was most often depicted as a falcon, most likely a lanner or peregrine, or as a man with a falcon head.[3] Etymology[edit] Horus was also known as Nekheny, meaning "falcon". Some have proposed that Nekheny may have been another falcon-god, worshipped at Nekhen (city of the hawk), with which Horus was identified from early on. Note of changes over time[edit] Khonvoum. Bambuti mythology.

Mehet-Weret. Mehetweret in Tutankhamun's tomb Mehet-Weret (mḥ.t-wr.t) is a goddess of the sky in Ancient Egyptian religion.

Her name means "Great Flood". Mulungu. Mulungu (also spelled Murungu, Mlungu, and in other variants[1]) is a common name of the creator deity in a number of Bantu languages and cultures over East and Central Africa.[2][3][4] This includes the Nyamwezi, Shambaa, Kamba, Sukuma, Rufiji, Turu, and Kikuyu cultures.[3][3][5] Today, the name "Mulungu" is also often used to refer to the Christian or Islamic God.

The Swahili word for God, "Mungu", is a contraction of the original form "Mulungu", which still appears in Swahili manuscripts of the 18th Century.[1] In some Bantu cultures (for example the Ruvu culture) the same word "mulungu" is also used with a distinct meaning, to refer to certain forest spirits; this homonymy has occasionally confused ethnographers and missionaries.[3] In traditional Bantu cultures[edit] Numakulla. Nut (goddess) Nut (/nʌt/ or /nuːt/)[1] or Neuth (/nuːθ/ or /njuːθ/; also spelled Nuit or Newet) was the goddess of the sky in the Ennead of Egyptian mythology.

She was seen as a star-covered nude woman arching over the earth,[2] or as a cow. Great goddess Nut with her wings stretched across a coffin A sacred symbol of Nut was the ladder, used by Osiris to enter her heavenly skies. Olorun. Olòrún is the Yorùbá name given to one of the three manifestations of the Supreme God in the Yoruba pantheon. Olorun is the owner of the heavens and is commonly associated with the Sun.

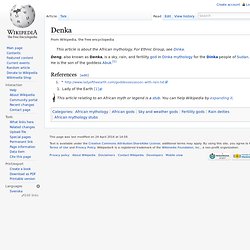

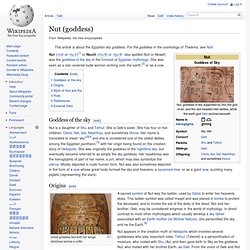

The vital energy of Olorun manifests in humans as Ashé, which is the life force that runs through all living things.[1] The Supreme God has three manifestations: Olodumare, the Creator; Olorun, ruler of the heavens; and Olofi, who is the conduit between Orun (Heaven) and Ayé (Earth). No gender is typically assigned to Olorun because Olorun transcends human limitations. Shango. Shango statuette This depiction of Shango on horseback has been attributed to the workshop of the renowned Yoruba carver Toibo, of the town of Erin. It was probably carved in the 1920s or 1930s for the timi (king) of Ede (one of the historic Yoruba kingdoms), who kept it in a shrine dedicated to the orisha (god) Shango.

Equestrian figures are potent symbols of power in many parts of Africa where ownership of horses was long restricted to warriors and political leaders. Shu (Egyptian deity) As the air, Shu was considered to be cooling, and thus calming, influence, and pacifier. Due to the association with air, calm, and thus Ma'at (truth, justice and order), Shu was portrayed in art as wearing an ostrich feather. Shu was seen with between one and four feathers. In a much later myth, representing the terrible weather disaster at the end of the Old Kingdom, it was said that Tefnut and Shu once argued, and Tefnut left Egypt for Nubia (which was always more temperate).

It was said that Shu quickly decided that he missed her, but she changed into a cat that destroyed any man or god that approached. Thoth, disguised, eventually succeeded in convincing her to return. He carries an ankh, the symbol of life. Hans Bonnet: Lexikon der ägyptischen Religionsgeschichte, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-937872-08-6, S. 685-689 → ShuAdolf Erman: Die Aegyptische Religion, Verlag Georg Reimer, Berlin 1909Wolfgang Helck: Kleines Lexikon der Ägyptologie, 1999 ISBN 3-447-04027-0, S. 269f. → Shu.

Umvelinqangi. Umvelinqangi is the Sky God from the Zulu mythology. He has a voice like thunder and is known to send down lightning bolts. He descended from heaven to marry Uthlanga, and is said to have created the primeval reeds from which Unkulunkulu emerged. Separate but related histories attribute male and female gender to a god with the same name and similar attributes. Utixo. Utixo or Tiqua was a god of the Khoi (the native pastoralist people of southwestern Africa), a benevolent deity who lived in the sky, sending rain for the crops, and speaking with thunder.

Utixo is sometimes translated as wounded knee. For an alternative pantheon see Khoikhoi mythology. One story that has survived in Christian literature, was that Utixo sent a message to his people that death would not be eternal. Unfortunately he used a rabbit to carry the message. The rabbit became confused, reversed the message, and ended up telling men that they would not rise again.

Utixo was the word that missionaries used for translating God into Khoikhoi. Xamaba.