Australian Aboriginal mythology. The Djabugay language group's mythical being, Damarri, transformed into a mountain range, is seen lying on his back above the Barron River Gorge, looking upwards to the skies, within north-east Australia's wet tropical forested landscape Australian Aboriginal myths (also known as Dreamtime Stories, Songlines or Aboriginal oral literature) are the stories traditionally performed by Aboriginal peoples[1] within each of the language groups across Australia.

All such myths variously tell significant truths within each Aboriginal group's local landscape. They effectively layer the whole of the Australian continent's topography with cultural nuance and deeper meaning, and empower selected audiences with the accumulated wisdom and knowledge of Australian Aboriginal ancestors back to time immemorial.[2] David Horton's Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia contains an article on Aboriginal mythology observing:[3] Antiquity[edit] An Australian linguist, R. Hawaiian mythology. Hawaiian mythology tells stories of nature and life.

It is considered a variant of a more general Polynesian mythology, developing its own unique character for several centuries before about 1800. Kaluli creation myth. The Kaluli creation myth is a traditional creation story of the Kaluli people of Papua New Guinea.

In the version as was recorded by anthropologist and ethnographer Edward L. Shieffelin whose first contact with them took place in the late 1960s. The story begins in a time the Kaluli call hena madaliaki, which translates "when the land came into form. " During the time of hena madaliaki people covered the earth but there was nothing else: no trees or plants, no animals, and no streams.

With nothing to use for food or shelter, the people became cold and hungry. Māori mythology. Māori mythology and Māori traditions are the two major categories into which the legends of the Māori of New Zealand may usefully be divided.

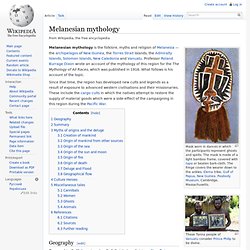

The rituals, beliefs, and the world view of Māori society were ultimately based on an elaborate mythology that had been inherited from a Polynesian homeland and adapted and developed in the new setting (Biggs 1966:448). 19th-century sources[edit] Missionaries[edit] Non-missionary collectors[edit] In the 1840s Edward Shortland, Sir George Grey, and other non-missionaries began to collect the myths and traditions. Melanesian mythology. Mask worn in dances in which the participants represent ghosts and spirits.

The mask is made of a light bamboo frame, covered with tapa or beaten bark-cloth. The fringe covers the wearer down to the ankles. Elema tribe, Gulf of Papua, New Guinea. Peabody Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Micronesian mythology. Micronesian mythology refers to the traditional belief systems of the people of Micronesia.

There is no single belief system in the islands of Micronesia, as each island region has its own mythological beings. Region[edit] Micronesia is a region in the southwest Pacific Ocean in a region known as Oceania. There are several island groups including the Caroline Islands, Marshall Islands, Mariana Islands, and Gilbert Islands. Traditional beliefs declined and changed with the arrival of Europeians in the 1520s. Federated States of Micronesia mythology[edit] Anagumang was a (probably legendary) Yapese navigator who led an expedition in rafts and canoes five or six hundred years ago.

Papuan mythology. The Papuans are one of four major cultural groups of Papua New Guinea.

The majority of the population lives in rural areas. In isolated areas there still remains a handful of the giant communal structures that previously housed the whole male population, with a circling cluster of huts for the women. The Papuan people are Melanesian people composed of at least 240 different peoples, each with its own language and culture. Sago is the staple food of the Papuan supplemented with hunting, fishing and small gardens. Ancestors are important, but not necessarily revered in Papuan culture. Religion[edit] The Christian church has been extraordinarily influential.

Art[edit] Papuan art forms are as diverse as they are distinctive. References[edit] Papuan Gulf Map. [1] 2000. Polynesian mythology. Polynesian mythology is the oral traditions of the people of Polynesia, a grouping of Central and South Pacific Ocean island archipelagos in the Polynesian triangle together with the scattered cultures known as the Polynesian outliers.

Polynesians speak languages that descend from a language reconstructed as Proto-Polynesian that was probably spoken in the Tonga - Samoa area around 1000 BC. Description[edit] A sacred god figure wrapping for the war god 'Oro, made of woven dried coconut fibre (sennit), which would have protected a Polynesian god effigy (to'o), made of wood. Prior to the 15th century AD, Polynesian people fanned out to the east, to the Cook Islands, and from there to other groups such as Tahiti and the Marquesas.

Their descendants later discovered the islands from Tahiti to Rapa Nui, and later Hawai‘i and New Zealand. From oral to written[edit] An example is provided by genealogies, which exist in multiple and often contradictory versions. Rapa Nui mythology. The Rapa Nui mythology, also known as Pascuense mythology or Easter Island mythology, is the name given to the myths, legends and beliefs (before being converted to Christianity) of the native Rapanui people of the island of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), located in the south eastern Pacific Ocean, almost 4,000 kilometres (2,500 mi) from continental Chile.

The myth of origin[edit] According to Rapa Nui mythology Hotu Matu'a was the legendary first settler and ariki mau ("supreme chief" or "king") of Easter Island.[1] Hotu Matu'a and his two canoe (or one double hulled canoe) colonising party were Polynesians from the now unknown land of Hiva (probably the Marquesas).