Structure. Types[edit] Physical structure[edit] In engineering and architecture, a structure is a body or assemblage of bodies in space to form a system capable of supporting loads.

Physical structures include man-made and natural arrangements. Functionalism (philosophy of mind) Functionalism is a theory of the mind in contemporary philosophy, developed largely as an alternative to both the identity theory of mind and behaviourism.

Its core idea is that mental states (beliefs, desires, being in pain, etc.) are constituted solely by their functional role – that is, they are causal relations to other mental states, sensory inputs, and behavioral outputs.[1] Functionalism is a theoretical level between the physical implementation and behavioral output.[2] Therefore, it is different from its predecessors of Cartesian dualism (advocating independent mental and physical substances) and Skinnerian behaviourism and physicalism (declaring only physical substances) because it is only concerned with the effective functions of the brain, through its organization or its "software programs".

While functionalism has its advantages, there have been several arguments against it, claiming that it is an insufficient account of the mind. Portal:Thinking. Formalism (art) First introduced by Roger de Piles (1635–1709), in his book the Principles of Painting, the technique of formal analysis was more fully developed by 19th-century art historians.

Leading proponents of a formalist approach to art history were, from the Vienna School of Art History, Moritz Thausing, who in 1879 became the second Ordinarius (full professor) of art history at Vienna, who advocated an autonomous art history and promoted the separation of art history from aesthetics. Thausing's students Franz Wickhoff (Professor 1891) and Alois Riegl (Professor 1897) furthered his approach, insofar as they developed the methods of comparative stylistic analysis and attempted to avoid all judgements of personal taste. Thus both contributed to the revaluation of the art of late antiquity, which before then had been despised as a period of decline.

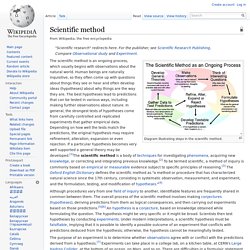

Roger Fry in Vision and Design (1909) was an early Modernist critic to apply formalist analysis to contemporary art. Scientific method. Diagram illustrating steps in the scientific method.

The scientific method is an ongoing process, which usually begins with observations about the natural world. Human beings are naturally inquisitive, so they often come up with questions about things they see or hear and often develop ideas (hypotheses) about why things are the way they are. The best hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested in various ways, including making further observations about nature. In general, the strongest tests of hypotheses come from carefully controlled and replicated experiments that gather empirical data.

Depending on how well the tests match the predictions, the original hypothesis may require refinement, alteration, expansion or even rejection. Although procedures vary from one field of inquiry to another, identifiable features are frequently shared in common between them. Overview The DNA example below is a synopsis of this method Process. Analysis. Analysis is the process of breaking a complex topic or substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it.

The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics and logic since before Aristotle (384–322 B.C.), though analysis as a formal concept is a relatively recent development.[1] The word comes from the Ancient Greek ἀνάλυσις (analusis, "a breaking up", from ana- "up, throughout" and lysis "a loosening").[2] As a formal concept, the method has variously been ascribed to Alhazen,[3] René Descartes (Discourse on the Method), and Galileo Galilei. It has also been ascribed to Isaac Newton, in the form of a practical method of physical discovery (which he did not name). Synthese. "A special section on Knowledge, Rationality and Action offers a platform for researchers interested in a formal approach to the process comprising rational behavior, from gathering and representing information, through reasoning and decision making to acting.

"[1] Notable articles[edit] Indexing & Abstracting[edit] In December 2012, Google scholar ranked Synthese as the most influential journal in philosophy.[2] See also[edit] Notes[edit] External links[edit] Editorial Board. Antithesis. Antithesis (Greek for "setting opposite", from ἀντί "against" + θέσις "position") is used when two opposites are introduced in the same sentence, for contrasting effect.[1][2] Description[edit] When there is need of silence, you speak, and when there is need of speech, you are dumb; when you are present, you wish to be absent, and when absent, you desire to be present; in peace you are for war, and in war you long for peace; in council you descant on bravery, and in the battle you tremble.

Antithesis is sometimes double or alternate, as in the appeal of Augustus: Listen, young men, to an old man to whom old men were glad to listen when he was young. Other literary examples[edit] Some other examples of antithesis are: A) Man proposes, God disposes. B) Give every man thy ear, but few thy voice. C) Many are called, but few are chosen. D) Rude words bring about sadness, but kind words inspire joy. Biblical use of antitheses[edit] The Jewish Encyclopedia: Brotherly Love states: As Schechter in J.